What distinguishes the architecture of housing and its primary expression, the apartment building? Variously termed urban, multiple and collective housing, what differentiates it from the individual house or from architecture more generally?

Housing as distinct from houses

All mass housing is forcefully tied to land and constructional economies.

Many new houses have a commissioning client, their brief tailored to bespoke requirements. While project homes sell bulk area at a cheap cost, sometimes architect-designed houses have generous budgets, allowing sectional play, complex inside/outside relationships and an array of fine materials and fitments.

By contrast, in multiple housing, future residents are unknown and more prone to churn over the building’s extended life. Clients for such housing tend to be agents, not the future occupiers: developer, spec- ulator, builder, lender, marketeer, variously from private, institutional or public sectors. The dominant real estate stereotypes and standardized plan “products” that typify the sector are poor surrogates for forward thinking on the multifarious ways we could live. Accordingly, housing so procured tends to be more generic.

In apartment buildings, areas tend to be tighter, relationships to the outside more succinct, sections usually a repeated stack. Housing contains common as well as private spaces: entry, stair, lift, gardens, carparks, utilities and occasionally roof terraces.

For houses, maintenance and future adaptations are options open to the owners. Whereas housing is more difficult to substantively adapt, needing the agreement of multiple owners. This tends to limit scope for personalization, while maintenance is cyclical and compliance-driven. Get the design wrong and you consign generations of future residents to economic, amenity and environmental suffering.

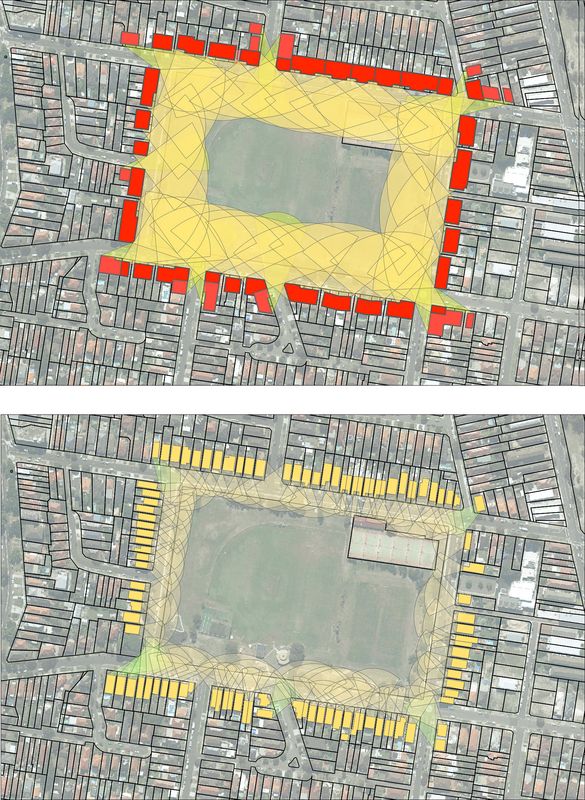

Based on the model of the English square, these diagrams illustrate the opportunity to increase the density of an established park, currently ringed by 100 individual houses, to hold between 850 and 1000 apartments. Based on a six-storey scale, every apartment could benefit from a park outlook.

Image: Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban Projects

Housing as the fabric of the city

Public space – the streets, parks, promenades and infrastructure – usually occupies 30–40 percent of the urban footprint. This is the long-established base in most cities, across continents and cultures, with the street structure claiming the greatest quantity of urban space. Housing dominates the remainder – perhaps as high as 80 percent of the combined area of each city’s blocks. Blocks bind the subdivision pattern, the enduring layer that is akin to the city’s DNA. Housing is inextricably tied to this lot structure. So the form and density of a city’s housing hugely contribute to its urban character and therefore way of life.

Housing definitions

In the limited area of architectural theory particular to housing, type provides the most pervasive intellectual and practical framework. The Enlightenment-era architect and theorist Antoine-Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy’s distinction remains fundamental: “All is precise and given … in the model, while all is more or less vague … in the type.”1 In practice, the model, an original idea or arrangement, may become the archetype, the progenitor of new type(s). Think for example of Pietro Lingeri and Giuseppe Terragni’s Casa Rustici in Milan or OMA’s Nexus World Housing in Fukuoka, Japan.

Type is the generic form of housing, replicated across cities, countries and epochs. Types are widely understood, although their origins are sometimes lost in history and culture. Everyone knows what a terrace house is, although few might trace its roots to the Adam Brothers’ Adelphi Terrace overlooking the Thames.

Many types can readily be named: courtyard house, freestanding house, cottage, villa, terrace house, row house and semi-attached pair. There are various specific apartment types: tower, slab, street wall, walk-up, courtyard and gallery access. Buildings can be an amalgam of types, such as a walk-up slab type.

The archetype is an exemplar of the type, due to the clarity of its form, organization and architectural qualities. Aaron Bolot’s 17 Wylde Street in Sydney’s Potts Point is an archetypal demonstration of the thin section, street wall type.

Much recent architectural interest has focused on hybrids. These may be characterized in multiple ways: a combination of several models or types; a bespoke or deluxe version of a type, in which its character overwhelms the type’s basic logic; a site-specific response; unusual juxtapositions of uses or adapted uses, such as industrial-to-residential conversions. Jackson Clements Burrows’s Upper House imaginatively melds the street wall, tower and communal roof terrace into a new synthesis.

In apartment buildings, type is determined by the relationship to the street and lot boundaries, the footprint relative to the lot, the passage from the street through the vertical and horizontal common circulation to the dwelling, the number and distribution of dwellings in relation to the common and exterior spaces and the section. The act of homecoming negotiates these conditions, passing from the public street through the communal spaces to the private world beyond the front door.

The house typically orients to its private backyard, discouraging interaction with the street and park. Designing mid-rise apartments to address the street and park can promote social inclusion and interaction.

Image: Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban Projects

Rules governing housing

Housing has long been subject to various rules and laws, often created in response to crisis, fiat or public interest. Fire, health and safety rules have pervaded urban housing since Roman times – the Building Code of Australia is just today’s version. Urban rules, governing the relationship to the street, height and site occupation, also sometimes extend to character, materials or aesthetic prescriptions. Amenity rules, such as New South Wales’s State Environmental Planning Policy Number 65 (SEPP 65), concentrate on light and air to interiors, privacy and spatial overcrowding.2

Drawing on this accumulated knowledge of success and failure raises the question of how best to draft housing rules. We must eschew simplistic strictures such as zoning or context, which tend to thoughtlessly replicate existing conditions. Rather than cloning sameness, what Australian cities need most is diversity (typological, not merely stylistic) allied to increased density to produce a heterogeneous urbanity that would intensify particular places.

Rich architectural traditions

The architectural history of housing reveals the interplay of the model and multifarious types – from the Roman insulae, their brick and concrete mass moulded by proto-metropolitan pressures, to the medieval townhouse (often an adaptable mix of workplace, home and lodging) on narrow-fronted lots squeezed within the walled town. There are borrowed models, such as the export of Paris’s Place des Vosges (the original Royal Square) via Inigo Jones’s Covent Garden to become the archetype for London’s squares of elite speculation. Hybrids too are not new, as Pierre Fontaine and Charles Percier’s Rue de Rivoli is a street wall residential transposition of the parti of Andrea Palladio’s Basilica in Vicenza.

The shifting trajectory of apartment buildings is invariably tied to cities’ periods of growth. New types respond to pressures and opportunities, be they population, politics, disaster or technology. Paris’s Haussmann-era apartment buildings line the percées of his boulevards, while postwar reconstruction in the form of towers and slabs was deployed across a bombed-out tabula rasa. Today we encounter the intensive regeneration of post-industrial land.

Over the past two centuries architects have played an increasing role in apartment design and urban housing, initially from speculation (the Adam Brothers’ Adelphi Terrace again) to the great early-twentieth-century social housing schemes such as the Amsterdam School or Red Vienna. Modernity made urban housing central to its progressive agenda, and the history of twentieth- century housing abounds in aspirational, if at times utopian, new paradigms.

In Australia, consider the successes of the first public housing in Millers Point and The Rocks (disgracefully under threat of sale by the NSW Government), Daceyville, the Griffins’ Canberra, Fishermans Bend social housing (as opposed to the current supercharged speculations), the South Australian Housing Trust or Brian Howe’s Building Better Cities enablement of affordable housing in the 1990s.

Where are today’s progressive demonstration projects, instigated and carried through with governmental oversight? Why the poverty of imagination and initiative by all tiers of government across Australia? With housing affordability a national crisis, why has housing our pop- ulation become just a sideshow to rampant speculation and comfy capital gains?

Conclusion

As architects, we need to master our disciplinary foundations, spanning type, urbanity, amenity and construction.3 We need to be inspired by the many successes (see Tokyo’s micro housing or Singapore’s green towers post-2000) and cautioned by the multiple failures (think European New Towns or Pruitt-Igoe). This is essential knowledge for the profession’s future, if we are to make the architecture of housing a staple of our work.

As Richard Weller and Julian Bolleter illustrate in their critical book Made in Australia, we must explore ways to accommodate a substantially growing population.4 Without a long-overdue national population strategy or enabling infrastructure, the take-up will be overwhelmingly in our established cities, with all the attendant pressures.5

We face twin perils. At the fringe, the unending obsession with car-dependent sprawl, so rapacious of land and resources and regressive in terms of sociability and health, should no longer be the default “planning solution.” Given our stubbornly low urban densities, what credible reason is there to extend the footprint of any Australian capital city? At the other extreme is hyper exploitation of mega enclaves around the core, such as Melbourne’s Docklands and Southbank, or Sydney’s Barangaroo and Darling Harbour, or Brisbane and Perth’s burgeoning facsimiles. We are enmeshed in an especially rapacious period, akin to the ravages of the 60s.

Instead we should reconsider the urban heartland, the inner and middle rings as Peter Myers presaged: “But it is not just a question of infill housing … [replacing] untold thousands of redundant single family dwellings that are too expensive to buy and maintain. Rather, what is needed is an entirely new type of housing that can be introduced into existing suburban tracts and which will, by virtue of its sound common sense, replace the dominant cottage type.”6 Obviously this means intensifying places around existing and projected public transport routes, but also privileged frontages around parks and waterfronts. We must ally higher density with high amenity, rather than consigning apartment buildings to just being strung along main roads or flung at railway corridor back lots. Why lodge the greatest number of people in the worst locations, reserving the better areas for undisturbed low-density houses? Of course, any such uplift must yield a public dividend of affordable housing, at a meaningful 20 percent minimum quantum with permanent tenure, rather than a desultory fraction on a sunset clause.

In the open city, the compact city, all forms of urban housing but particularly the apartment building will be crucial. Already in Sydney and Melbourne over half the new dwellings are apartments. But density alone is not enough. It is our responsibility as architects to infuse these inert quantities with intangible qualities, to make dignified facades enlivening streets, to introduce a robust character pervaded by environmental design, to promote social inclusion and interaction, to create genuine variety and choice, to envisage beauty while providing the framework for joy in everyday life. It’s our responsibility and great opportunity.

This article is based on the keynote address given by Philip Thalis for the Housing Futures symposium held in July 2015 by Architecture Media.

1. Antoine-Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy, The True, the Fictive, and the Real: The Historical Dictionary of Architecture , translated by Samir Younés (London: Andreas Papadakis, 1999), 255.

2. State Environmental Planning Policy Number 65 (SEPP 65) has operated in New South Wales since 2002, supplemented by the new “Apartment Design Guide” in July 2015.

3. The fierce Melbourne debates on long-overdue amenity and design standards would benefit from a fuller understanding of urban housing – see ARM Architecture, “Just functional is dysfunctional,” ArchitectureAU website, 3 September 2015, architectureau.com/articles/just-functional-is-dysfunctional/ (accessed 28 October 2015).

4. Richard Weller and Julian Bolleter, Made in Australia: The Future of Australian Cities (UWA Publishing, Perth, 2013).

5. Such as a Very Fast Train along the east coast, built in stages from Maroochydore to Geelong.

6. Peter Myers, “Seeking the Section,” Architecture Australia , April 1992, 22–25.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 30 Mar 2016

Words:

Philip Thalis

Images:

Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban Projects,

Rod Simpson

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2016