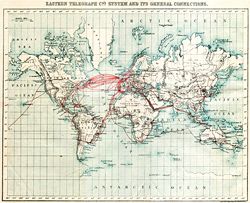

Chart of submarine telegraph cable routes by The Eastern Telegraph Co., showing the global reach of telecommunications in 1901.

Submarine telecommunication cables around the world (2007).

Bharat Dave reflects on globalization and outsourcing design and documentation.

Globalization has long been present on Australian shores, first as a destination of the colonial projects and currently as a source of design and construction talent operating in the global arena. With the Indian Ocean along one coast and the Pacific on the other, any change that gathers wind somewhere in the world, especially in Asia or America, washes over Australian shores sooner or later, sometimes depositing opportunities and other times eroding established grounds. The outsourcing of design services to offshore locations is one such recent change that has now swept onto our shores.

Whether to sail this wind of change or to sidestep it entirely is a choice that might be helped by scanning the horizons a bit wider. The phenomenon of “outsourcing” of discrete services in design professions is not entirely recent. Architectural practices, for example, have traditionally relied upon specialist model makers and “perspectivists” to communicate and document design intentions. Multi-location design offices are known to strategically cultivate some branch offices as specialist nodes of skills and knowledge. The increasing formalization of aspects of design and construction knowledge has led to distinct specializations – for example, civil, structural, mechanical and other engineering services. Design teams have long operated by drawing upon diverse expertise using a form of internal or external outsourcing supported by informal or formal protocols.

The most substantive change that has occurred now is a recalibration of geographic and temporal constraints on patterns of work, a change that underpins the offshoring phenomenon and is enabled in part by key advances in information and communication technologies. One was the development of personal computers in the early 80s, which spread the power of computing to a larger number of individual users.1 The other was the development of the World Wide Web in 1991, which accelerated an increasingly denser web of communication around the globe. The global uptake of digital technologies and communication networks was complemented by the increased availability of a digitally skilled workforce from regions with differing wages and costs of living. The cumulative impact of these forces reconstituted global markets for goods and services, and offshoring emerged as one possible organizational strategy for design services to compete at home and abroad.

The consequences of these transformations for design professions have arrived in both small and big measures. With design documents becoming increasingly digital and portable over communication networks, the production and exchange of design information become unhinged from the constraints of geography and time. Tasks that were tied to a place or a team in-house become transportable and transferable. Digitization of design information and documents, in turn, accelerates the modularization of tasks so that they can be flexibly assigned and executed. It is but a small step, then, to move specific tasks completely out of the office. Design documentation and detailing tasks, having traditionally evolved to a point where they may be delegated to dedicated staff in the office, now become a target for not just outsourcing but offshoring as well.

The early signs of offshoring in the design sector appeared in the late 90s in the USA, a market which accounts for 23.5 percent of estimated global architectural employment but earns the largest share, 33 percent, of global architectural design services revenue.2 With labour wages accounting for nearly 40–50 percent of design practice costs, it is no wonder that offshoring service providers sprang up in regions where a skilled workforce with lower labour costs and a well-serviced communication infrastructure were available.

It may also explain why the genesis of many early international providers of offshore architectural services in India is traceable to one or more American practices. Although India looms large as an offshoring service provider of architectural documentation in the global markets, it has company: the Philippines, Vietnam, China, Mexico, South America, the Caribbean, eastern European countries, and to some extent South Africa.

The literature on offshoring of architectural services is largely anecdotal, with few detailed, publicly available studies. The true magnitude of offshored design services may be much smaller or much bigger than is widely believed. Here is one proxy measure. Almost a decade after they were founded between 1997 and 2002, four international offshore production houses backed by venture capital are still operational; have reportedly expanded over the years; have primary bases or operational centres in countries including the UK, the USA, India and Vietnam; and between them employ about 1,500 staff worldwide. One of these firms claims annual revenue approximating US$10 million.

The earth may have gone flat – however, it does not guarantee equal gains and losses everywhere. There are many potential hurdles and downsides associated with the offshoring phenomenon: the loss of cumulative and shared professional culture, the disappearance of particular skills, and the erosion of entry level jobs that typically provide passages for fresh graduates to the world of professional practice. The fears are well founded and the impacts real, including some anticipated with the introduction of digital technologies in the design and construction sectors.3 The offshoring of design services has also taken root in Australia. However, little reliable data about its scale are publicly available.4 Its onset may be tracked by a rise in the number of offshoring service providers setting up front offices in Australia. It is also substantiated in the course of research we undertook recently.5 Piecing together various fragmentary accounts suggests that construction documentation is an attractive target for offshoring among Australian practices. It accounts for about 30 percent revenue, but with wages representing about 40 percent of practice costs, any reduction in time spent on construction documentation may help lift the operating profit of Australian practices from the current 12.5 percent closer to the global average of nearly 29 percent.

This proposition is certainly attractive. However, our research on offshoring alliances suggests that what may be theoretically conceivable may not be feasible or achievable in practice, and certainly not uniformly by all sizes of design practice, due to a variety of reasons. Following the initial rise of offshoring services in the late 90s, the offshoring bubble has gone through a couple of wobbles and appears to have shed large amounts of unrealistic cargo (and also mercenary operators). Debates about the benefits and costs of offshoring are still ongoing, with one certainty: neither stubborn denial nor unquestioning subscription to these changes helps articulate future courses of action. With the usual caveats about predictions, here are some possible developments to watch in the future.

Quite a different prospect comes into view if we do not focus on offshoring in isolation. The issues at stake may no longer be about where production of design documents occurs or who carries them out or how fast they are routed around the world. Bill Mitchell offered a useful shift in this perspective: “Buildings were once materialized drawings, but now, increasingly, they are materialized digital information – designed and documented on computer-aided design systems, fabricated with digitally controlled machinery, and assembled on site with the assistance of positioning and placement equipment.”8

Instead of remaining fixated on “documents” and their value for design development, visualization and communication, or construction documentation, we can focus directly on the endgame: “materialized digital information”. Increasingly seamless and tighter connections between tools for definition of geometry and material fabrication are already available. What if portions or entire buildings were outsourced or offshored? The possibility is not far-fetched. We already have production and supply networks in which iron ore mined in Australia is shipped overseas for processing, only to return to Australia as customized, fabricated building components ready for assembly. Where might such a trajectory take us in the future? Perhaps designs that are conceived in Australia, modelled and rendered in India, documented in Vietnam and fabricated in China? Surely that will reflect – literally and metaphorically – bits of practice that are on the move, outsourced or offshored, to the East or the West.

Bharat Dave is associate professor of architecture at the University of Melbourne.

1. IBM PC was launched in 1981, followed by Apple Macintosh in 1984.

2. All data are based on “Global Architectural Services” (February 2010) and “Architectural Services in Australia” (January 2010), industry reports issued by IBISWorld.

3. Mike Cooley, Architect or Bee? The Human/Technology Relationship, Langley Technical Services, 1980.

4. An exception is a project on which the staff of Hassell worked with an offshore design documentation service to deliver a project in the Middle East, as documented in a research thesis in 2006.

5. Digital Outsourcing in Architecture, a research project funded by the Australian Research Council and carried out by P. Tombesi, B. Dave, B. Gardiner and P. Scriver, based at the University of Melbourne and Adelaide.

6. “‘Offshoring’ has lost meaning, says Nasscom”, Business Standard, 23 July 2010 (http://www.business-standard.com/india/news/%5Coffshoring%5C-has-lost-meaning-says-nasscom/395660/)

7. Jonathan Glancey, “Our future’s been outsourced”, Building Design Online, 19 March 2010, http://www.bdonline.co.uk/comment/our-future%E2%80%99s-been-outsourced/3160280.article

8. William Mitchell, “Constructing Complexity”, Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Aided Architectural Design Futures, Vienna, Austria, 20–22 June 2005, pp. 41–50.