Architecture concerns more than buildings. Raeburn Chapman explores the important nexus between architecture, transport and the city.

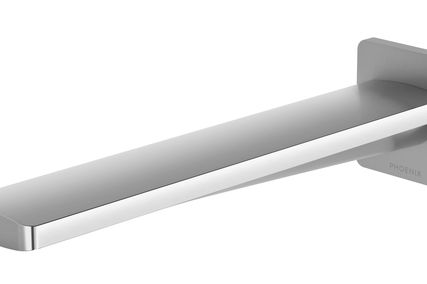

Eastern Distributor at Surry Hills. Built outcome by Conybeare Morrison.

Eastern Distributor, architectural model by Jackson Teece.

It is incumbent upon architects to help shape and contribute to the quality of all built environments, beyond the scope of individual buildings or a site ensemble. Transport infrastructure is surely the biggest and most critical shaper of cities and urban space, from the downtown to the suburbs and beyond. It influences the way we use and experience cities and is the most visually dominant artefact in the built and natural landscape. Consequently, transport infrastructure should not simply be the preserve of engineers, just as the suburbs should not be left to developers. So what is the meaning of this for architecture? To avoid the philosophical trap perhaps just two types of example may be instructive.

Exactly how far-reaching a difference architecture can make is highlighted by Sydney’s Eastern Distributor motorway. The original engineering design would have cut a swathe through the city in the name of traffic efficiency, as had already happened with freeways in the 1960s. Because the real problem was one of city design, getting the project right required a different approach.

An urban design framework was prepared for the entire corridor and its distinctive precincts as the basis for an integrated engineering, architectural and landscape design for the motorway.

The resulting facility, architecturally influenced, is a three-dimensional solution with a vastly different footprint. It forms a gateway into Sydney with a “Lynchian” motorway experience that makes the city imageable. The design leaves the existing urban fabric intact. It continues the local street grid and, by alleviating through-traffic, has enabled more public transport to be designed into a district-wide road network. Public space is significantly improved – for example, the building of the land bridge that extends the space of the Art Gallery of NSW to form a parkway precinct with the Domain.

In the Surry Hills precinct to the south, Moore Park has been developed from a parking lot into a major green space with terracing along the motorway edge.

The motorway is designed to protect the Victorian heritage architectural townscape and neighbourhood opposite, and to give it a frontage. With its through-traffic removed, streets reinstated and a network of vest-pocket parks developed, this neighbourhood is being refurbished as a sought-after inner-city living environment. What we have here is a total design conception and process that responds to “place” and historic context, “greens” the city and brings corridor-wide benefits. The corridor might otherwise have succumbed to the worst excesses of development.

In the light of the “transit architecture” projects published in Architecture Australia of Jan/Feb 2007, including the Parramatta transport interchange in Sydney, it is also worth revisiting the work by architect/ engineers in the Station Design Office of the French National Railways. This work is part of a national agenda to build multi-modal interchanges as transport hubs that can be a catalyst for urban development and redevelopment. For example, the redesign and renovation of Saint-Charles station in Marseilles is part of a larger urban conception: it stitches the station into the fabric of the city and furthermore provides a framework for the transformation of a vast area between the station on the hill and the port.

French station designs reinstate the “grand station” in contemporary terms. Integrated and transparent spaces are created. They are “seamless” from railway platform to concourse and street levels – to reveal the city when arriving, allow visibility throughout and spill into the city. The spaces are a joy.

The more we extend our horizons to incorporate urban design – shaping the city – the greater the value of architecture. Transport infrastructure (and the patterns for all modes of movements) is a key part of urban design. The nexus between architecture, transport and the city is as relevant to the formation, functioning and character of the suburbs as it is to city centres and, indeed, the entire metropolis.

Raeburn Chapman is Senior Urban Design Advisor, Roads & Traffic Authority, NSW.

Graeme Gunn reflects on the difficulties and pleasures of a lifetime in architecture and the “Building Industry”.

Apart from family, Architecture has been the cornerstone of my existence for more than 50 years. At the age of 22 I relinquished a tantalizing bucolic existence in a pleasant regional town to throw my sombrero into the ring and embrace the more intensive urban culture of Melbourne. From that date on, Architecture took centre stage.

Earlier, my post-secondary educational years were spent, selectively, in the “Building Industry”, in the employ of my father, a builder who had been thumped by the depression of the late 1920s. I developed a serious distaste for the intricacies of that industry, yearning instead for the experiences of controlled space, form and texture and for the skill to orchestrate them.

Ironically, years later I learned that my male ancestors had been carpenters and builders. One was a ship’s carpenter who travelled on the Sirius as part of the First Fleet. Another, an immigrant from Scotland, arrived in Australia in the year 1846, settling as a builder and coffin maker at Dunkeld in Victoria’s Western District. Obviously there must be a residue of sawdust in my bones, or, as some have less charitably remarked, in my brain.

For me, the getting of Architecture, while essential to my existence, has not been easy. She has been elusive and often out of reach, with many of my attempts at initiating a union often unrequited. Developing a relationship to the act of consummation has at times required an intensive and difficult effort, while at other times, praise the Lord, she has appeared responsive, pliable and all-giving. Nothing has been consistent and the results of our union have been unpredictable. Often the results have been extraordinarily fulfilling, offering titillation, excitement and exultation. At other times they have been flat, uneventful, innocuous and humiliating, and for these latter shortcomings I blame myself.

This self-blame is directed at a lack of insightfulness as to what constitutes the basis of a rewarding relationship, an inability to distinguish between want and need and the failure to acknowledge that foreplay – for example, searching for the unknown and finding the unexpected – is required as a prelude to mutual satisfaction from a collaborative act.

Long-term relationships can have their problems. Often, following the initial rush of enthusiasm and ensuing gratification, and some repeats, relationships can alter. Sometimes the initial energy diminishes as other aspects of the union open up. Not as pulsating, perhaps, but stronger and more encompassing. Less selfish and more accommodating. And a preparedness can develop to share with others the joys of cohabiting with Architecture and all her wares.

Enter the client, a potential major contributor to the relationship. Now we have a ménage a` trois. More difficult to manage, certainly, but eventually more satisfactory because more are contributing and as a consequence more are benefiting from the fruits of the union.

It is a brave and clever soul, however, who steps with skill and confidence beyond the parameters of a ménage a` trois to embrace a builder and the plethora of consultants swarming within the “Building Industry”. And then includes them in an encompassing “love-in”, where trust, endeavour, skill and passion are equally matched, ensuring a masterful, stimulating and enduring product worthy of their intellectual loins.

If, however, an increase in the number of less-than-capable contributors determines the fortunes of the relationship, then Architecture will suffer and languish. Little of substance will be produced, and those who once loved her will move on to embrace less illustrious passions, where no doubt they will perform like underdone meringues.

Another telling factor about why Architecture in particular matters to me is contained in part of a letter recently received from a client:

“Dear Graeme, ›› The numbers … have now been positioned on the front of the house (albeit crookedly) and I thought this was an apt moment to write and thank you for all the hard work and effort you and your team … have put into the design and build process …

Once something like this is complete it is easy to forget how many hours, days, weeks and, in this case, years went into creating a building that is truly exceptional and a pleasure to live in.

I would have never been able to embark on this project if it hadn’t been for you and Dad. Your combined experience, patience and wisdom helped me through the process and I feel privileged to have worked with you both. I know in decades to come that I will view this project as a great achievement.”

Graeme Gunn is a Melbourne architect.

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 May 2007

Words:

Graeme Gunn,

Raeburn Chapman

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2007