How can architects empower themselves and their cities to reduce the operational emissions of buildings? How can they create a higher level of resiliency to cope with the imminent impacts of climate change?

These are some of the questions I have been able to ask through my research, thanks to a Byera Hadley Travelling Scholarship.1 I’ve collated insights from more than 30 architects, policymakers, builders, suppliers and supporting organizations across three case-study cities – Vancouver, New York and Brussels. And the conclusion I’ve drawn is stark: the Passive House (Passivhaus) standard has been the cornerstone of the emission-reduction strategy across all of these cities, not only for architects driving better building design, but for government as well.

Passive House – a voluntary standard for energy efficiency – has experienced an exponential increase in global uptake since being launched in 1990 in Germany. It has become the international best practice for interior comfort and occupant wellbeing, regardless of climate. It also caps the amount of operational energy used to just 15 kWh/m 2 a, meaning it can help cities achieve their emission reduction targets, tied to the 2015 Paris Agreement.2

Gillies Hall at Monash University’s Peninsula campus by Jackson Clements Burrows Architects demonstrates that Passive House is a viable option for large residential projects in Australia.

Image: Peter Clarke

With a foundation in building physics, the standard has become a key tool for architects, as it enables the qualitative design to be supported by quantitative data. Highly accurate predictions around a building’s performance can be generated by adhering to five simple principles, allowing architects to validate and analyse design decisions. Certification also acts as a transparent quality-assurance process, ensuring the required as-built quality is actually achieved through onsite verification methods, such as mandatory inspections and airtightness testing.

Sebastian Moreno-Vacca3, founder of Brussels architecture firm A2M, explains that energy is the “fourth dimension of design” – it should inform us, enrich the design process and, ultimately, provide an outcome that benefits both people and the planet for generations to come. “The language of energy needs to be integrated into the vocabulary of architecture,” he tells me. “Without understanding energy flows, it would be like designing a building whilst blindfolded.”

With mounting pressure from industry and global politics, governments in each of the three cities I studied have shown leadership around emissions reductions – particularly in the building sector. A key strategy has been the implementation of a “backcasting” approach to building performance standards, where governments define one specific end goal – namely, zero-emissions buildings – and then work backwards to develop policies and programs that will achieve that goal.

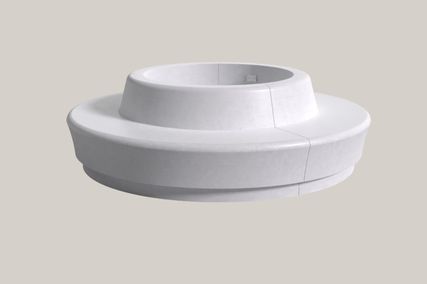

With its 11 apartments almost entirely sealed, The Fern in Sydney, by Steele Associates, is Australia’s first Passive House certified apartment building.

Image: courtesy Steele Associates

This has led to municipalities establishing their own zero-emissions building plans and deploying incentives to encourage developments to meet the Passive House standard as a pathway to compliance. Building excellence competitions have been launched in conjunction with these programs to encourage and reward architects and developers who are willing to step up to the challenge.

In Brussels, the Exemplary Buildings Program (BatEx) was launched as a financial incentive aimed at driving energy-efficient construction and increasing market demand. To be eligible for BatEx funding, projects had to meet a range of stringent criteria and be informed by Passive House guidelines (though meeting the standard was not mandatory). The program ran from 2007 until 2013, with six calls for entries resulting in 243 buildings receiving funding across the Brussels- Capital region. By the time it ended in 2014, it had funded the construction of buildings covering 621,000 square metres, with more than half of this being passive .

In this short time, the construction industry underwent a vast transformation, not just in terms of building performance, but also in terms of economic uplift. By 2012, the initial €45 million dedicated to the BatEx program had already generated €319 million in business turnover, creating more than 1,200 jobs and initiating the revitalization of some of the most economically disadvantaged areas, according to the EU-funded Passive House Regions with Renewable Energies project.4

With its 11 apartments almost entirely sealed, The Fern in Sydney, by Steele Associates, is Australia’s first Passive House certified apartment building.

Image: courtesy Steele Associates

In 2015, the benchmarks of the Passive House were incorporated into Brussels’ regional building code, transforming a city that had some of the poorest performing buildings in Europe into a global leader in less than a decade. Brussels has become a source of inspiration for cities that wish to make dramatic and effective changes to their building policy in order to reduce their carbon footprint while also benefiting their economy.

New York is adopting a similar approach, with its Buildings of Excellence scheme launched by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority and supported by the Building Energy Exchange (BE-Ex). It represents a key strategy to accelerate industry transformation to achieve the Passive House standard and meet the obligations of the Climate Mobilization Act passed in 2019.

In each city, “building excellence centres,” such as BE-Ex in New York and ZEBx in Vancouver, were set up to join the dots between the public and private sectors, and to establish a clear strategy of support for industry transformation. It is important to note that architects have often been at the heart of these initiatives, forming cross-disciplinary and inter-city communities through such centres, and bringing together “innovators” who, together, can lead high-calibre climate action through the built environment.

These are just a few success stories that offer inspiration as we forge a new future for our construction industry on home soil. The shift has already begun, with almost 30 buildings in Australia having achieved Passive House certification at the time of writing. Among these are several large-scale developments, such as Gillies Hall at Monash University by Jackson Clements Burrows Architects, for which I was part of the core design team, and The Fern apartment building in Redfern by Steele Associates. More than 80 additional projects are in the pipeline across the country, in both the private and public sectors.

There is reason to be optimistic about the role architects can play in finding solutions to our current climate crisis. I hope my research will spark inspiration in the architectural community and broader industry, especially in times of such uncertainty.

Kate Nason’s report Green Light: the rise of the energy-efficient building can be viewed at on the NSW Architects Registration Board website.

Read more articles and interviews from the climate and biodiversity emergency series.

1. The Byera Hadley Travelling Scholarships enables students or graduates of a degree from an architecture school in New South Wales to travel overseas in order to broaden their experience in architecture.

2. Operational energy is the amount of energy required to operate a building over its life, including for heating, cooling, lighting and appliances. The Passive House standard has nominated 15 kWh/m 2 a (i.e. 15 kilowatt hours per square metre per annum) as the maximum load.

3. Sebastian Moreno-Vacca is speaking at the South Pacific Passive House conference in Sydney on 9–11 October 2020.

4. For more information on this project, see passreg.eu.