The entry to the restaurant. Image: Anthony Browell

Details of the voluptuous facade. The unglazed window frames on the third-level roof terrace curve with the perimeter wall. Image: Anthony Browell

Interior of the restaurant on the ground floor. Image: Anthony Browell

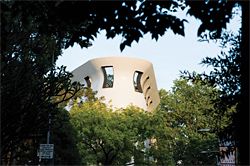

The character of the building emerges on approach from Ward Avenue. Image: Anthony Browell

The roof terrace is punched with unglazed windows that frame a particular vista of the surrounding roofscape. Image: Anthony Browell

When I was a teenager there was a popular song by Lloyd Cole and the Commotions, the chorus of which ran “she’s got perfect skin”. Not being gifted with same I found the song unfair – why just her skin? What about her other qualities? Kings Cross is full of skin, very little of it perfect, and it is the skin of Durbach Block’s new building on Roslyn Street that became its most contentious feature.

The new building occupies a pointy triangular site fronting Roslyn Street and Kellett Way, just off Darlinghurst Road in Kings Cross. The site is well known in Sydney as the former home of a late night bar called Baron’s, generally considered a venue of last resort, the end of the line for keeping a late night rolling. I wasn’t a Baron’s aficionado but the nights I did end up there were memorable for their seediness, drunkenness and extended after effects. NSW licensing laws make independent late night venues scarce, so Baron’s was a place of folklore, a greasy firetrap where love affairs were started and dissolved, the birthplace of stories much recounted. A vigorous campaign to save the place was mounted during the planning approval process, including a Save Baron’s petition signed by over a thousand people. Such were the passions aroused that Camilla Block recalls dread at attending social functions lest her role in the bar’s apparent demise be discovered.

Durbach Block looked first at options for alterations and additions but there was little of the original villa left. Upgrading to Code would have required such substantial work that it was deemed practically impossible. Demolition of the existing building and the design of its replacement were approved by City of Sydney planning but rejected by council. The rejection was a straightforward political answer to the public outcry but the primary stated reason was a lack of fine-grained response to the local conservation area. Independent experts (other architects of note) were called in to pronounce the design inappropriate. None would. Throughout all this the client – Ron White, Cameron White and Damien Pignolet for the Woollahra and Bellevue Hotels group – stood by the project and, in a first for Durbach Block, it ended up in the NSW Land and Environment Court. The issue became one of skin, white skin, in reference to the colour of the tiles with which the building would be clad. Was it typical of the area? How white was white? How shiny? A DA condition was drafted mandating a certain percentage of white and off-white tiles of specific glossiness or otherwise, depending on location. Subtle variation of the finish had been a design intention from the outset – bizarrely, it was through a Dadaesque quantification of this subtlety that the two-year saga was resolved.

And so to this skin. Number 5–9 Roslyn Street, now known as “Barcelona”, is clad from top to toe in glazed white and biscuit coloured tiles. The tiles appear to be broken, each an irregular shaped piece roughly the size of the palm of a hand. Trencadis is the word used in Spain for this finish; it is a Catalan term for a type of mosaic that uses broken tile shards from cast-off tiles and other ceramics. In Spain it is a finish evocative of early-twentieth-century Spanish, or more specifically Catalan modernism, most famously Gaudi. At “Barcelona” the tiles give the building an evenly stretched and gently glimmering surface. Looking closer, the subtle variations emerge. The tiles are slightly glossier lower down the building and more matt further up. Inversely, there are fewer off-white tiles at the upper levels. Occasionally they peel up or aside to reveal a cast concrete subsurface, or steel-lined opening, but mostly they make possible the smooth cladding of the building’s many curves. And it is a building of curves, a building as body rather than as backdrop to bodies, coaxing light into the streets and square around it.

“Barcelona” is clad from top to toe in glazed white and biscuit coloured tiles. The tiles appear to be broken, each an irregular shaped piece roughly the size of the palm of a hand.

In principal the brief was very standard: commercial offices, a restaurant on the ground floor, a bar on level one and service functions in the basement. The budget wasn’t large and the small site, 200 square metres, is tightly planned. One of the most impressive aspects of the project is the playful and generous result wrought from this normative base. Each doorway and window eddies and inflects, shifting across the facade. At the third floor the office space opens onto a terrace with punched unglazed windows in its tilted and curved perimeter wall, each framing a peculiar vista of the surrounding roofscape. Bathrooms and staircases seem to have wriggled into the spaces left over for them, assuming a comfortable if unusual form.

The use of tiles as an external finish in Australia could be pursued at length. At the other end of the spectrum from the Sydney Opera House, most pubs have a decorative tiled finish over their ground floor walls. It is thus common in the area around Roslyn Street and its use on this building is both logical and contextual, an ordinary material to which we have become so accustomed as to be blind. The ebullience with which the tiles are applied here makes the familiar foreign – “uniquely familiar” as one friend of Durbach Block put it. It is a quality that occurs throughout this project, and one pertinent to the criticisms levelled against it during planning approval. Contrary to council’s objections, much about the building is a response to and interpretation of the local context. The stretched skin with punched openings, the glazed street level and the curved inflection at the top with its gesture towards oversized cornices – all resonate with the area. In each case the contextual starting point is taken and manipulated, wittily, to create something new.

Neil Durbach says that he has long had an interest in corner sites such as this one, “accidental sites”, which exist across Sydney through a misfit of grid and topography. Viewed from Darlinghurst Road the building sits comfortably in the street, an element of the surrounding ground. Only from Ward Avenue to the east does it emerge as a figure, comprehensible in three dimensions. Here the sharp corner is celebrated with a tight but graceful curve, with curved glass sliding windows and a swooping awning. A three-dimensional curve is generated as this radius meets the sectional inflection at the roof terrace. The builders, Beebo Constructions, used specialist boat makers to fabricate the formwork in plywood. Their workmanship across the project is formidable and the result is an architecture of specific moments, large and small. The building itself is a moment in the fabric of the city and the Cross, a character, at once mischievous and delightful.

There are criticisms. More could have been made of the section, which is essentially a flat stack. The roof terrace with its strange framed views and quirky geometry would have made a better bar than the first floor. But these are minor in the face of the Hollywood ending. When the scaffolding came down, writer and local resident Mandy Sayer, an outspoken critic of the redevelopment, was instantly converted. “The design … is so exquisite and unique that I feel as if Kings Cross is about to unveil its own equivalent to the Sydney Opera House,” she wrote. What’s more, she refers to a friend living near the construction site who fell in love and moved in with one of the construction workers. This is pure Baron’s! Sayer’s was not the only retraction the office received. Something in the building’s jaunty aspect has translated the folklore of the old use into form, and the passions of the tiny niche group called architects have for once dovetailed happily with those of the local community.

Credits

- Project

- 5–9 Roslyn Street, Kings Cross

- Architect

- Durbach Block Jaggers Architects

Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Project Team

- Neil Durbach, Camilla Block, David Jaggers, Lisa Le Van, Stefan Heim, Deborah Hodge, Brigitte Thearle,

- Consultants

-

Andrew Darroch

Accessibility consultant Morris Goding Access Consulting

Builder and construction manager Beebo Constructions

Commercial kitchen Austmont Catering Equipment

Electrical consultant Shelmerdines Consulting Engineers

Environmental consultant Aurecon

Fire engineering Stephen Grubits & Associates Sydney

Heritage consultant Stephen Davies

Hydraulic consultant Whipps Wood Consulting

Mechanical consultant Nappin and Associates

Planner Mersonn Pty Ltd

Structural consultant SDA Structures

- Site Details

-

Location

5–9 Roslyn Street,

Kings Cross,

NSW,

Australia

Site type Suburban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Commercial