Between the covers a snapshot of architectural photography in Architecture Australia.

“It is strange that, in an age so alive with scientific thought, we still have the spectacle of make-believe pervading the practice of photography … We attempt to idealise the subject instead of assessing its value as an objective fact. As Lewis Mumford said, the mission of the photograph is to clarify the subject.” Max Dupain

A cursory glance at contemporary architectural magazines, including Architecture Australia, suggests that Max Dupain’s suspicions still have relevance. Buildings are often photographed under exceptional circumstances using pre- and post-production technology to enhance or exaggerate their attributes. “Just how many purple sunrises are too many?”, one might ask. In an increasingly competitive market, the pressure to idealize architecture in photographs often begins with the commission by the architect. John Gollings describes this relationship with candour:

A symbiotic relationship has always existed between architects and their photographers.

For instance, Seidler and Dupain, Cox and Moore, Ezra Stoller and Mies Van der Rohe, Ando and Futagawa, the list goes on. Both professions are commercial arts depending on patronage and working with the inherent limitations of client requirements and budgets.

Photographers need good buildings to photograph and publish for a living, architects depend on good photographs to promote a design or attract new clients.

Much has been written about the idealizing capacity of photography. In 1944, Walter Benjamin caustically observed that in the hands of exponents such as the German photographer Renger-Patzsch, “the ‘New’ or Modernist Photography could idealize anything”. More recently, Thomas Schumacher argued that “Architects today use the photograph as a form of pornography. It is perfect, clean and ‘air-brushed’, with no odour, no hair, no warts. More importantly it has become a substitute for experience.” Such criticisms may be overstated, but they alert us to the power of the architectural photograph, a power which can be productive, problematic and pleasurable.

Australian architectural photography has evolved over one hundred and sixty years, preceding the Journal of the Institute of Architects of New South Wales by six decades. The magazine has published striking professional photographs of buildings, both Australian and international, since its inception; the first building so reviewed was the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Today Architecture Australia continues to be an important vehicle for disseminating the architecture of this country, and this is generally illustrated through the work of Australia’s leading photographers.

So, at the risk of oversimplification, here are some of the more significant milestones in Australian architectural photography’s history.

Just two years after Louis Daguerre’s scientific discovery was announced at the French Academy of Arts and Science in 1839, photographers were using the daguerreotype process in Australia. Colonial photographers such as Henry Beaufoy Merlin and Charles Bayliss (New South Wales), Richard Daintree, Antoine Fauchery, Charles Nettleton and later Melvin Vaniman (Victoria) were commercial operators who documented Australia’s early settlements – from goldfield diggings to city monuments and streets. Photography of Australia’s built environment continued into the early twentieth century, and this is exemplified in the pictorialist work of Harold Cazneaux (1878–1953). “Caz” was a prolific photographer of landscape, people, fashion, home interiors and gardens, most notably for The Australian Home Beautiful and The Home magazines, but his work also appeared in the pages of Architecture. He used darkroom techniques to further soften the effects of mist, fog, smoke, steam, cloud and rain – to create painterly impressions through the manipulation of daylight. Cazneaux recorded the development of Sydney in thousands of uncommissioned photographs and some of his later work, for example Bridge Pattern (c. 1934), anticipates the Modernism that would typify the younger Max Dupain’s work.

The shorter history of Australian architectural photography properly begins with Max Dupain. By the 1930s Dupain was aware of Modernist or “New Photography” published in overseas magazines such as Das Deutsche Lichtbild. Characterized by dramatic points of view, reductive composition and close-ups of everyday subject matter, these images presented the familiar in unfamiliar ways. Australia’s buildings at the time were not generally impressive by European or American standards, but Dupain used prosaic Sydney city views as inspiration for his Modernist interpretations. He also came to have some of the most highly acclaimed architects in the country as longstanding patrons – John D. Moore, Sydney Ancher, Harry Seidler, Philip Cox, Glenn Murcutt, Ken Woolley, Lawrence Neild, Andrew Andersons, Alexander Tzannes, Ed Lippmann. In Seidler’s case the relationship lasted nearly forty years.

Dupain’s photographs helped to build the reputations of these architects, and he, in turn, amassed a comprehensive portfolio.

The work of Wolfgang Sievers and Mark Strizic, two Melbourne-based émigré photographers, paralleled Dupain’s. Sievers studied at the Contempora School in Berlin and his interest in architecture was rekindled in the 50s and 60s through commissions by eminent Melbourne practitioners such as Frederick Romberg, Peter McIntyre, Robin Boyd, Roy Grounds, Buchan Laird and Buchan, Yunken Freeman, and Bates Smart and McCutcheon.

Strizic’s photographs are more poetic than Sievers’ dramatic images. He gained his interest in and knowledge of photography in Australia rather than Germany. He worked with editors Neville Quarry and David Saunders on the University of Melbourne’s highly regarded broadsheet Cross Section, and published Living in Australia with Robin Boyd in 1970. Three of Strizic’s favoured photographs were of the 1959 Lloyd House. The titles – Space, Homage to Robin Boyd; Soul, Homage to Robin Boyd and Structure, Homage to Robin Boyd– suggest his high regard for Boyd, and his understanding of architecture.

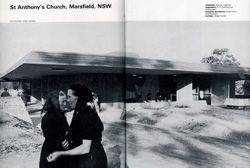

As Modernism began to be questioned towards the end of the 1960s, photographic practices also began to change. Harry Sowden, who worked in Australia during this time, advocated a more inclusive approach known as “reportage” or photojournalism – “tell it the way it is”. In his book Towards an Australian Architecture, Sowden took a swipe at the exponents of Modernist photography, writing that “[he] avoided the usual formal methods employed in architectural photography – the meticulously staged full facade shots where people, cars and other uncontrollable objects are rigidly excluded … The job that architectural photography must do is to recreate the experience of a building … I think this cannot be done by showing buildings as a series of isolated monuments tortured on the rack of a wide angle lens.” Sowden’s approach was widely accepted by the profession and was often published in Architecture in Australia.

In 1974 the Sydney architectural photographer David Moore wrote “Thoughts on the Photography of Architecture”, published in Architecture Australia the following year. It reflects attitudes formed during his years as a photojournalist with The New York Times, Life, Fortune, The Observer and others. Moore appealed to building users and to the reader’s common sense by saying that it “should be possible to photograph well any building in existing conditions if it is worthwhile architecture”. He cited the Sydney Opera House as a building which could be photographed from most vantage points under any weather conditions with good results. The argument is difficult to refute, but were architects detached enough from their work to commission such an independent photographer? There is little evidence in the published work of the period to suggest that their patronage supported a photojournalistic approach. After all, such a technique was unlikely to produce “art”, and that is what the majority of architects sought.

By the late 1960s something else was also changing architectural photographs – the demand for colour reproduction. Journals had to compete with television and popular magazines. Theirs was a polychromatic world in which illustrations recognized what many architects had long denied – that colour was an integral part of the built environment. By the 1970s colour in architecture became a seriously regarded design element. In Melbourne, John Gollings worked closely with Peter Corrigan to produce a portfolio of “constructed” images of polychromatic architecture based on multiple exposures and poetic-theatrical intent. Gollings’ photography infuriated some, delighted others and continues to stimulate debate.

Many photographers seek to explore the potential of new, rather than old technology.

At a lecture to the New South Wales Chapter of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects on 11 July 1994, John Gollings said that we are already living in the “post photographic era”. He meant that photographs may be digitally scanned and manipulated using personal computers and readily available software. Previously, architectural photographers had interpreted their subject with the aid of various films, lenses, points of view and darkroom techniques.

Nevertheless such images could be generally regarded as evidence of the building’s basic proportions, structure and materials. Gollings was, however, flagging a new era of architectural photographs – one offering unprecedented potential for radically reconfiguring architecture’s context and components, even falsifying its very existence. There is a certain irony here – accuracy and credibility were precisely the perceived failings of perspective drawings before the invention of photography.

Photography has great influence in architecture. Comparatively little knowledge of recent architecture is gained by first-hand experience: most of it is known only through images.

Photography is the principal means of communicating new ideas and processes, and architectural photographs continually present new perspectives on buildings and the built environment. Yet despite this influence, relatively few Australian photographers work exclusively in architectural photography. (Two notable exceptions are Peter Hyatt, editor of Steel Profile, and Patrick Bingham-Hall, publisher and editor of Pesaro Publishing.) By the mid-1990s there were around one hundred professional architectural photographers nationally – most of them also accepting a wide range of other kinds of commissions. A generation earlier, when Australian architectural photography was still comparatively young, the leaders were Max Dupain, David Moore,Wolfgang Sievers, Richard Stringer and Fritz Kos.

This handful established standards for the photography of Australian architecture for the 1960s and beyond. Their work appeared frequently in Architecture Australia and its predecessors, and thereby became well known to the broad architectural profession. Two generations on, John Gollings, Patrick Bingham-Hall, Anthony Browell, Trevor Mein, Brett Boardman and Jon Linkins are among the country’s most prominent photographers, and their work appears frequently in the pages of the magazine. The link between particular photographers and Architecture Australia and its predecessors is significant. Regular publication and acknowledgment in the journal bears an unofficial but implicit imprimatur of acceptance by the architectural profession.

Architecture Australia and its predecessors have showcased the work of some of Australia’s finest photographers, and in doing so have made a wide range of buildings available for public consideration. Despite my caution about the power embodied in architectural photography’s links to the print media, I trust that this educative and inspirational role will continue.

Adrian Boddy

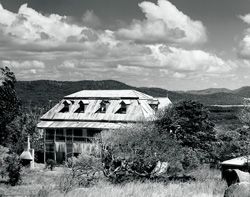

ONE OF my chief pleasures is photographing some of the old buildings in Queensland. Older buildings weather and accumulate softening vegetation and give lovely romantic photographs.

Some of the most delightful buildings are those in ruins.

Richart Stringer

PATTED ON the head, officialized as “vernacular” and marginalized by the Eurocentric architectural blatherers who continue to infest our country, the beaten-up buildings of early Australia endure as a nineteenth-century version of Critical Regionalism (if you like). A European model adapted to the local climate and the local lousy budget.

Richard Stringer and Wesley Stacey photographed these buildings in a most tender and direct manner. Their photographs are without corniness – without the Norman Rockwell lens that was appropriated by many of their peers.Wesley Stacey’s photographs survive in an endearing series of books including Historic Towns and Colonial Towns. Richard Stringer is mainly known to me through his photographs for many National Trust books in the 1970s.

The photographs illustrating the Architecture in Australia feature of December 1974 on Richard Stringer’s work are of Cooktown Convent. Twenty-seven years later, I photographed Rex Addison’s addition to the convent (now the James Cook Museum). Stringer’s photographs are much better than mine, but he did have one undeniable advantage – his subject was eighty years old, mine was a little baby, not even a month old.

Stringer and Stacey photographed “real” architecture in “real” Australia. Their legacy is invaluable.

Patrick Bingham-Hall

I REMEMBER one picture he took for Syd Ancher of a particular house. I think it was in a bush setting and the house was quite linear. In the foreground was a rock with leaves on it, and there’s light coming down illuminating that rock. Although it’s not only an excellent photograph of the architecture within the environment, that foreground detail I think is absolutely magic and it’s stuck in my mind for a long time.

David Moore from an interview by Patrick Bingham-Hall on 6 August 2001 for a proposed book on Max Dupain’s Photography of Sydney Modernist Architecture.

I’VE CHOSEN to discuss this particular photograph, not because I took it, but because I like the idea of “imagery” coming along in between all the “information”.

Architectural photography, in order to fulfil its charter, has to be explanatory and illustrative; it has to show the reader how the building works, how it feels to be beside or within it, and how it looks: it has to be informative.

As part of any coverage of a project, I think it’s important to include an impression, an interpretation, however symbolic or romantic – if for nothing else then to show how you personally feel about the building.

There is magic somewhere in most things, and it is good to take a bit of it home.

Anthony Browell

IT IS THE composition with the central tree that I like. It gave credibility to many of my own early shots, but was done in the early 1950s. The split frame bothers a lot of people because it makes the building secondary to the composition but also more memorable.

John Gollings

ADJOINING THE house he designed for his mother, Rose Seidler, this house for the Rose family by Harry Seidler was a pure and minimal response to a construction ideal. The photograph by Max Dupain responded perfectly to those ideals.

Since his arrival in Sydney, Harry Seidler has involved his brother Marcell in the photography of his work. Key exteriors of the Rose Seidler House and the Meller House were photographed by Marcell, who was an enthusiastic cameraman, using the large format camera equipment required for the photography of architecture.

Marcell, however, needed to pursue his manufacturing business in Australia and he had heard of the worth of a photographer in Sydney called Max Dupain.

He suggested that Harry give him a go.

The first project ready for photography was the Rose House (c. 1950). Since the end of World War 2. Max Dupain had been eagerly accepting architectural assignments, encouraged by Syd Ancher. Sam Lipson, before WW 2, was probably his first architectural client.

So when Dupain arrived at the Turramurra location it was a moment of portent. This is thought to be the first negative he exposed at Seidler’s behest and a forty-year professional collaboration ensued which both challenged and rewarded the participants and Australian architecture.

Eric Sierins

THE SCALE and brooding foreign nature of the Victorian Arts Centre burnt into my psyche as a twelve-year-old on a country school excursion. I regarded it at the time as ugly and fascinating. Eight years later as an architectural student I felt it to be one of the most beautifully resolved whole structures, full of light play, spatial conflicts, reference to movement in space, interplay of inside to exterior space and time. Its grand fortress facade still moves me. I look forward to its renovation in twenty years’ time.

Trevor Mein

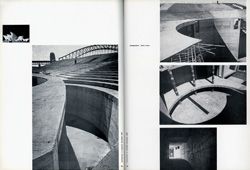

FEW PHOTOGRAPHS of architecture have achieved a monika in the style of the keyhole shot of Australia Square Tower. Such is the imagery and mastery of form, shape and light that Max Dupain has brought to this exterior shot, that it defines itself in one word like a popstar or a rock singer. In Dupain’s case, however, it would be more like the synergy of a Beethoven symphony rolled into one seminal moment of previsualization and film exposure. The total experience of the curve set against the towering verticals and the girl who, as I understand it, was asked to hold that position by Dupain.

It was a major city project by Lend Lease under Dusseldorp’s direction. In 1997 Harry Seidler recalled Dupain taking the photograph, “… he picked that [shot] totally – I thought [we’d shoot it] from the plaza to explain the whole thing … Max’s shot is fantastic I think, the way he gets the graduation of the light and to extract the most out of an object, rather than purely telling an architectural story …the abstract compositional aspect – that was his artistry.”

Eric Sierins

BEYOND RECORDING the architectural project, in the most memorable architectural photography there is a desire both to interpret the work and to reveal something of its idea.

These images represent the potential of the camera to move beyond the document or record and to serve as translators of the authors’ work. It is fitting to speak in the past tense when describing photography. Photographs of architecture not only allow us to stand in sometimes inaccessible places, but perhaps most importantly, they allow us to re-enter an inaccessible time. These are enviable moments that can only be visited thanks to the skill of the photographers.

David Moore’s photographs of the Opera House (Architecture in Australia, December 1962) form part of a larger series of articles that were presented during the course of its construction (Architecture in Australia, September 1960, December 1962, April 1968). The presentation of the building process over a period of years demonstrates that editorial policy then was less concerned with displaying the singular heroic image of completed architecture as fetish object. Moore’s images remind us that architecture is temporal in both its process and its experience: the result of complex human interactions. This complexity was revealed in a series of photographs showing us a site of archetypal forms revealed in the characteristic hard light of Sydney. Beyond straightforward documentation, Moore was able to excavate multiple meanings.We are presented, not with iconic shells, but with a monumental sundial, a cavernous industrial site with workers as ant-like silhouettes, and monochromatic abstract compositions of steel and concrete.

Max Dupain’s image of Seidler’s Australia Square (RAIA Year Book 1968–1969, November 1968) offered a portal to a future of Australian architecture. Heroic Modernism is framed, reaching infinitely upward, supported by the rational, mathematical engineering of Nervi and a system of prefabricated construction. The image reveals a photographer acutely aware of the decisive moment: that time when the materiality and the detail of the architecture are best exposed. Dupain provides further architectural information, scaling and dating the building with the “fashionable” inclusion of contemporary models.

John Gollings’ work with Edmond and Corrigan from the 1970s to early 1980s (Church of the Resurrection, Keysborough, 1975–76; Freedom Club childcare centre, Keysborough, 1975–77; Kay Street Housing, Carlton, 1981–83) demonstrates that beyond a technical virtuosity and understanding of the photographic medium, memorable photographs are the product of a creative relationship and implicit understanding between architect and photographer.

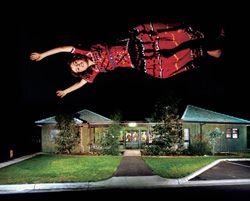

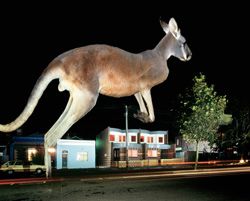

The architecture was shown as controlled studio set pieces often photographed at night.

Gollings literally “shed light” on his subjects by supplementing the existing architectural lighting with his own, emphasizing the artificiality of the built landscape. Enigmatic figures of kangaroos, flying children and priests inhabit these postmodern landscapes where mythologies and narratives of Australia were exposed and explored.

Brett Boardman