Review Elizabeth Grant

Photography Georgie Sharp

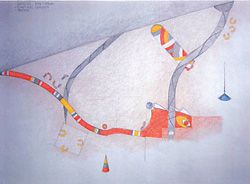

Conceptual drawing of movement through the court buildings. The presence of Arkurra, the Spirit Serpent of the Flinders Ranges Dreaming, acts as a wayfinding mechanism to lead people to the main entrance. Secondary paths lead to an outdoor shelter.

The double-height circular foyer is lit by diffused natural light. The simply etched wooden panels around the perimeter of the foyer illustrate pre-European life including significant historical events of the Port Augusta region.

Expansive views of the Flinders Ranges and the gulf seen from the foyer, forging a strong relationship between inside and the natural landscape.

The Magistrates’ Court is also used as an Aboriginal Sentencing or Conferencing Court. The organic shape of this court reflects the shape of the roundtable used in the Aboriginal Court. Photograph by Ben Wrigley.

Elevational view of the courts complex.

The outdoor shelter is a multifunctional shade structure that can be used as an outdoor court. Photographs by Georgie Sharp are courtesy of SA Life.

Port Augusta balances on the tip of Spencer Gulf, a geographic meeting place of the ranges, gulf, desert and plain. The massive scale of the Flinders Ranges frames the stark beauty and expansiveness of the unrelenting landscape. A sense of journey is integral here. Port Augusta is the gateway to the outback and an important transient point and settlement area for European Australians and meeting place for Indigenous Australia.

Alongside the permanent Aboriginal population of Port Augusta of people from over twenty different language groups, there is a fluctuating population of Aboriginal peoples from the north and west of South Australia and beyond. This mobility occurs according to a number of “lines” or “paths” reflecting attachments to place by birth, kinship ties and traditional ownership of country. Aboriginal peoples also travel to Port Augusta to access a multitude of services (including the justice system) not available in remote areas.

The design of a new court complex for the region needed to take into account the complexities and importance of the place, the need to service a large number of matters across a wide range of jurisdictions and the socio-spatial needs of different client groups and organizations. With many of the users identifying with Aboriginal cultures, there was an opportunity to move beyond traditional court architecture to integrating the traditions and needs of various Aboriginal peoples into the design. In order to achieve this, the design team (including architects, artists and landscape designers) consulted closely with the Indigenous and non-Indigenous stakeholders. The application of extensive participatory planning and consultative processes resulted in the project receiving an Institute Commendation for Collaborative Design.

The site for the complex was sectioned from the neighbouring railway yards. It lies adjacent to the main business centre of Port Augusta and commands distant views of the Flinders Ranges, with shorter views of the Minburie Ranges and Spencer Gulf. The two-storey complex is constructed of a combination of lightweight materials such as corrugated iron in natural and pre-coloured finishes, fibre sheet and copper cladding against precast concrete and texture-rendered walls. To develop open and non-intimidating architecture, large areas of glass were used to allow visual connection with the outdoors. In some areas, timber-louvred sections and artwork were used to provide shading or privacy screening. The colour palette for the building’s exterior was chosen by matching the colours of various Flinders Ranges ochres. A hierarchical order was then given to the choices – colours reminiscent of important ceremonial ochres were chosen for imposing sections of the exterior. The building reflects the adjacent landscapes, with alternating colours taking the viewer’s attention as the sun moves through the course of the day.

The complex sits along the long axis to the street frontage, with a series of long, low sand mounds planted with spinifex mirroring Port Augusta’s landscape. Between the mounds, mass plantings of indigenous plants soften the building and keep the visitor to pathways while allowing privacy and views under the canopy zones. Visitors arriving at the street frontage are led along the main pathway, which is coloured grey and represents Aboriginal contact with the European criminal justice system. The path intersects with another path where a depiction of Arkurra, the powerful and feared bearded Spirit Serpent of the Flinders Ranges Dreaming, is laid out. The presence of Arkurra acts as a symbol and as a wayfinding mechanism leading people to the main entrance. At the entrance, another path allows diversion. This allows people an important deviation should they sense conflict in the public or entrance areas and wish to collect their thoughts or wait outside. The secondary path leads to an outdoor shelter.

The outdoor shelter is a simple, open shade structure repeating the roof lines of the court complex. The shelter commands magnificent sweeping views over the Minburie Ranges and Spencer Gulf. A multifunctional structure, it is used for a range of consultations where privacy is necessary as well as an external waiting and reflection area. The need for relief from court processes, by being able to get outside the building and feel the sun and wind on your face, is central to reducing stress among Aboriginal users. The shelter has been designed to accommodate outdoor courts (although it has not been used for this purpose at this stage). Seats within the outdoor shelter (and around the exterior of the site) are three-dimensional translations of Aboriginal depictions of people sitting. The seats allow two or three people to sit as a group but are situated in relation to each other so that direct eye contact can be avoided (necessary in many Aboriginal cultures) between people seated in different seats.

Once at the entrance to the complex, the visitor notes Arkurra’s head sitting under the front verandah, with his beard protruding as geometric shapes from under the verandah screens. His elliptical eye appears as a pattern in the cement and nearby a high cone shape symbolizes his tail breaking the ground outside the building. Looking into the building, people are able to directly view the layout and key destinations and can orient themselves in the open and readable organizational system. There is a common registry with separate and discreet reception for the Youth Court, with its own foyer, conference area, interview room and amenities.

The entrance leads into a double-height circular foyer. The area employs extensive glazing to offer views of the ranges and the gulf, continuing the strong relationship between the interior and exterior of the building. Just below the ceiling, elements of local history are represented in a frieze using a series of simply etched wooden panels. The panels illustrate pre-European life and historical events such as the arrival of Captain Flinders and the establishment of Port Augusta as an industrial hub. Moveable organic-shaped seating fulfils its intended purpose and provides children with diversion as they move the seats to form new shapes. Arkurra’s path continues, denoted by the leaves of mangrove stems pointing to the doors of each of the courtrooms.

The complex has three courtrooms opening from the circular foyer: a jury court, a magistrates’ court and a multipurpose court. Each court has a courtyard to provide visual relief and continue connections with the external environment. The magistrates’ court also doubles as an Aboriginal Sentencing or Conferencing Court. The Aboriginal Court concept originated in South Australia to address the mistrust Aboriginal peoples have with the criminal justice system. It provides the offender with opportunities for direct and meaningful engagement with the judiciary, Elders, family and community and connects action and consequence through intense focus. The design of the Aboriginal Court at Port Augusta departs from the traditional rectangular courtroom layout, with an organic space to administer traditional sittings and the roundtable used in the Aboriginal Court. Space is compressed by the use of retractable screens, which accentuate the focus on the significant circle of participants. The need for light and short and long views was acknowledged in the use of large areas of glazing, offering views of internal courtyards and of the gulf and ranges. Five slump glass panels frame one of the views and depict the story of Seven Sisters Dreaming. This narrative exists in many forms throughout Aboriginal Australia and is shared by Aboriginal communities as far north as the Kimberley right down to Port Augusta. The story reveals Aboriginal knowledge of the night sky as well as the strict moral and social codes.

The Port Augusta Courts Complex attempts to respond to the needs of Aboriginal peoples in the justice system, recognizing the social and legal issues that face Aboriginal communities by striving to remove some of the barriers associated with the Western justice system. It is a significant and unique court building, which has attempted to articulate the accessibility, accountability and transparency of the judicial process while responding to and respecting the cultural attitudes, socio-spatial needs and beliefs of the Aboriginal peoples. Rather than alienating Aboriginal users, it presents architecture that reinforces the viability and splendour of Aboriginal Australia.

Dr Elizabeth Grant is a lecturer at the Wilto Yerlo Centre for Australian Indigenous Research and Studies at The University of Adelaide.

PORT AUGUSTA COURTS

Architect

Department for Transport, Energy and Infrastructure (DTEI)—project architect Denis Harrison; project team Paul Drabsch, Ian Abbott, Brian Carr.

Interior designer

DesignInc.

Landscape designer

Viesturs Cielens design.

Artists

Cath Cantlon and John Turpie (facilitators), Donald McKenzie, Regina McKenzie, Lavene Ngatokorua, Deb Williams.

Structural and civil engineer

Wallbridge & Gilbert.

Services engineer

BESTEC.

Acoustics engineer

VIPAC.

Project manager and cost manager

DTEI.

Contractor

Candetti Constructions.

Client

Courts Administration Authority.