<b>REVIEW</b> Laura Harding

<b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> Michael Nicholson, Patrick Bingham-Hall, Brett Boardman

Detail of the York Street facade, showing the transition between the “old” and “new” fabric. The massing of the new work follows the light wells and verticality of the original building.

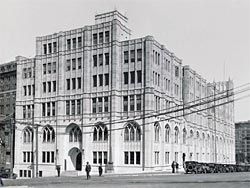

The competition-winning proposal for the Scots Church assembly building, 1927.

Scots Church and Assembly Hall c. 1931. Five floors had been completed when construction was halted. Image courtesy of the State Records Office of New South Wales.

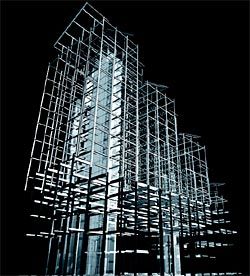

Three-dimensional study of the conversion, which fills the volume of the initial design, but within the contemporary sloping height plane.

An interior view of a standard double-height apartment.

A new apartment in the existing heritage building.

The northern facade overlooking Lang Park. The changing pattern of orange solar blinds animates the facades.

Sketch of the carefully worked facade.

Oblique view of the striking York Street elevation. The stepped form responds to the City of Sydney’s receding height plane, with a series of “sky follies” meandering above and between the towers.

The debate surrounding the relationship between contemporary architecture and heritage fabric has been passionately contested over many decades, but has, in recent times, been marked by the negotiation of a comfortable architectural truce. It is now quite acceptable to propose a forthright contemporary addition if it formally defers to its heritage neighbour. “Old” and “new” are at liberty to revel in their own time and tectonic if the moment of their meeting is orchestrated with deft, clinical precision – pared down to the barest of minimums and articulated by a wary and respectful distance.

Opportunity for such politely staged segregation in the contemporary addition to Scots Church, Sydney, was limited. Rosenthal, Rutledge and Beattie’s Presbyterian assembly hall and church offices were themselves substantially incomplete. The result of an architectural competition held in 1927, overseen by the Institute of Architects and adjudicated by Norman Weekes (the City Engineer responsible for the 1920s design of Hyde Park), Mr O. Beattie’s Neo-Gothic proposal was ultimately intended to fill the envelope delineated by the city’s 150-foot height limit in a monumental expression of “the universal character and inherent nobility of Presbyterianism and the material consummation of the church’s pioneer efforts in this new world of Australia”.1 Only the first five floors and the assembly hall had been completed when construction work was abandoned following the onset of the Great Depression.

Despite its evident rigour, the Scots Church assembly building was marked by contradictions – it displayed an eccentric simultaneity of ecclesiastical and commercial expression, and an authoritative self-confidence that was at odds with its incomplete and fragmentary nature. The assembly hall is the original building’s most curious and notable feature. Buried within the centre of the building, its elliptical form grazes the York Street facade but is essentially hidden within its taut, orthogonal skin. The only hint of its presence is offered on the Margaret Lane frontage, where it momentarily swells beyond the predominant structural line before sweeping back into the building where it is anchored in the thickness of the plan.

Tonkin Zulaikha Greer’s recent addition was also a competition-winning scheme – the result of a limited competition conducted as part of the City of Sydney’s Design Excellence programme. The contemporary brief called for the completion of the building with a volume equivalent to that of the original proposal. The new works needed to accommodate a change in use from commercial to residential and also address current planning codes, which included a sloping height plane that brutally pitched at 45 degrees from north to south along the site. The angled height plane is the city’s rather blunt method of preserving solar access to its important open spaces – and Wynyard Park is located immediately to the south of the Scots Church site.

Tim Greer of TZG credits the City of Sydney’s competition process with broadening the discussion and scope of important city projects at a critical moment – the commencement of the design and documentation process. The competition system is valuable in that it gives the city a voice as the “client” and lends the winning proposal a level of support and acknowledgment that helps to steel it for the fierce battles that inevitably accompany commercially challenging projects of this type. Despite this, the responsibility for defending the integrity of the project still falls all too heavily on the architect and, as such, the architecture itself must be focused, shrewd and selective.

TZG’s new volume is highly respectful and keenly curatorial in its response to the massing of the original building. Eschewing the introduction of a politely prosaic setback that would allow “new” to hover deferentially above “old”, the formal massing of the building is drawn from the alignment of the existing base and enmeshed with that of the original, characterizing the new work as the completion of a unified architectural project, as opposed to an aloof, objectified addition. The York Street elevation is particularly striking – the dignified verticality of the structural rhythm is carefully referenced in the new volume and the three original light wells are remade as deep cuts that retain the building’s formal intent as a cluster of articulated city towers. On the northernmost tower, where the lateral wall of the predominant housing module is revealed as a comparatively solid elevation, a tracery of linear seaming in the zinc panels visually extends the compositional patterning of the base, terminating at a level that marks the city’s original 150-foot height limit.

The northern facade is constrained by the inset alignment of the existing structure, which prevents it from adopting the subtle articulation of the central three bays and achieving the lean verticality of the York Street side. On its southern faces, the new work valiantly battles the strictures of the height plane – pleating and folding the building’s facades to enliven the ponderously even stepping imposed by the commercial imperative to fill the envelope. A series of folded interstitial roofs or “sky follies” playfully meander above and between the towers – contemporary “grotesquerie” that culminates at the northern edge of the building, where they hover beyond the facade in a manner that Greer attributes to “that Sydney tradition of doing anything to catch a glimpse of the harbour”.

Moments of resistance that anticipated the subversion of the architectural intent during the construction process were strategically embedded in the building, providing idiosyncrasies that have enabled TZG to retain an extraordinary amount of variation in apartment types and layouts. Fewer than half of the 148 apartments resemble the standard module, with elements such as the pleated southern facades and existing heritage elements used opportunistically to induce particularity and complexity throughout the project. The standard apartment type is deftly worked to maximize its efficiency. Reminiscent of the Corbusian unite module, each has a lower living level and a bedroom mezzanine, spatially unified by a double-height atrium and wintergarden that imbues each with the vertical disposition of the gothic base. Thoughtful but spare detailing offers moments of raw tactility – plasterboard is peeled back to reveal the fretted ceiling structure and define the dining space, castellated steel stair risers respond to the shifted alignment of the kitchen joinery below, while a linear floor grille at the bedroom/bathroom threshold provides unexpected glimpses between levels. Such elements offset the jarring remnants of site battles lost – including the clumsy imposition of airconditioning elements in the bedroom spaces that openly flout the building’s integrated natural ventilation and cooling strategies.

The deliberate formal control of the new work is contrasted with a more ambivalent and provocative material sensibility that allows the fabric of the addition to engage with contemporary environmental demands. An intensively worked facade unit offers each apartment a high degree of environmental operability. Thin louvred panels and a secondary layer of bi-folding doors with integrated sashes permit controlled natural ventilation without exposing the interiors to the acoustic intrusion of the city’s traffic snarls. Alternatively, a large sliding door set within red, tapered aluminium reveals can be retracted to draw dramatic urban vistas and the unimpeded life of the city directly into the domestic realm. The shifting calibration of vibrant, orange solar blinds forms a variable mosaic that records the intermittent traces of human occupation and use on the building’s facade.

With its addition to Scots Church, TZG has constructed a lively, shifting discourse between halves of an architectural whole separated by more than three quarters of a century. The provocative addition resists the imposition of a singular ideological response to the original building, deftly alternating between moments of considered conservation and deliberate disparity. This approach neatly negotiates the contradictory character of the original building itself and opens the work to contemporary environmental and programmatic agendas. More broadly, the project proposes that “old” and “new” be allowed to breach their customary distance and tentative dialogue – so that each may engage in a more vital and spirited interrogation of the other. One hopes that they are increasingly given the opportunity to do so.

›› LAURA HARDING WORKS WITH SYDNEY-BASED PRACTICE HILL THALIS ARCHITECTURE + URBAN PROJECTS. SHE WISHES TO THANK PHILIP THALIS FOR HIS THOUGHTFUL COMMENTARY REGARDING THE ORIGINAL SCOTS CHURCH BUILDING, WHICH INFORMED THIS REVIEW.

PORTICO, THE SCOTS CHURCH CONVERSION, SYDNEY ›› Architect Tonkin Zulaikha Greer Architects—project team Tim Greer, Paul Rolfe, Wolfgang Ripberger, Trevor Williams, Georgia Webb, Ruth Leiminer, Yannick Goldsmith, Kon Vourtzoumis, Roger Sullivan, Brian Zulaikha, John Chesterman, Angela Rheinlaender, David Jackson, Michael Bennett, Jan Ly, Helen Hughes, Trina Day, Bettina Siegmund. Project manager, quantity surveyor and builder Westpoint Constructions. Engineer Van der meer Bonser. Heritage consultant Brian McDonald and Associates. Environmental and mechanical consultant Hyder Consultants. Acoustic consultant PKA Acoustic Consulting. Electrical consultant Donnelley Simpson Cleary. Hydraulic consultant DCH Hydraulics. Lift consultant Norman Disney Young. Planning and BCA consultant City Plan Services. Fire engineer Defire. Surveyor Rygate & Co.

›› ENDNOTE 1. Competition Adjudicators Report, 1928, from ScotsChurch and Assembly Hall Conservation Study by John Graham & Associates, 1992.