Ronan Moss of Riddel Architecture discusses the opportunities for sustainable development in retrofitting heritage buildings.

Sustainable development is moving us towards a fundamental shift in our collective design consciousness. While architects and designers are becoming more engaged with environmentally responsive design and materials, this needs to be accompanied by a shift in attitude towards the way we approach the adaptive reuse of our 200 years of built heritage.

It is widely recognized that one of the biggest challenges in “greening” the industry is working out how to make our existing buildings more sustainable. With existing buildings substantially outnumbering new buildings, they are the greatest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, clean water wastage, energy wastage and poor indoor air quality.

Compared to other countries, Australia is moving very slowly in this area. While the concept of green retrofits is paid lip service, there are few examples that demonstrate to the industry how successful these buildings can be in terms of their significant life-cycle-cost savings, their energy reduction and their increased level of habitability. It is important that we develop green retrofit models in our own climate and conditions, creating a diverse range of local buildings available to visit and learn from.

Retrofitting buildings for sustainability delivers a suite of financial and environmental benefits. Projects of this nature work internationally because there is an established industry, with knowledge and experience. They understand the particular challenges posed by upgrading existing buildings compared to new build projects. Due to growing demand from this industry, the commercial sector is actively competing for improved market edge by committing to green strategies and the triple bottom line of good economic return, environmental sustainability and social sustainability. In Australia the federal government is proposing to release legislation on the mandatory disclosure of energy bills for commercial buildings prior to sale, which is likely to quicken the shift to an equally competitive green market here. It will compel building owners and developers to upgrade their assets, vastly decreasing life-cycle cost and, as a result, increasing total value. When market competition starts informing the sustainable agenda, the move to greener cities will be more quickly realized.

One of the fundamental obstacles we are facing is that long-term sustainability has become a race against time. The longer we wait to retrofit our cities and towns the less time we will have to develop sound models for best practice. Faced with this we need to ask ourselves, what do we want our future towns and cities to look like? The move towards sustainability will ideally encourage increased urban density, less development on greenfield sites, improved public transport and infrastructure, a shift away from anti-pedestrian design and a reduction of car use, leading to less congestion. Other initiatives we could improve on in time could be reducing our food carbon by embracing urban farming or cooperatives on the fringes of the city. This in turn will reduce the ecological footprint of the city while simultaneously creating a better environment to live in. For these changes to occur there will need to be broad development strategies introduced; these will only be achieved by a shift from all players in the industry and a decision to move away from the current solution of greening one building at a time.

An inevitable amount of new work will become available to architects when decisive action is taken to retrofit our cities. While this will provide many exciting design opportunities, consideration of the unique challenges posed by this new work will need to be carefully assessed. One of the things we should learn from the last thirty years is to measure how successful the attitude of short-term low-cost construction has been. Building it cheap to demolish it in the future has left us with buildings whose high embodied energies probably won’t successfully integrate with a retrofit for longer term use. I believe there are a few criteria that are critical to a good working outcome.

- Older buildings are often constructed differently from new buildings and need to be carefully manipulated so that their long-term building life and sustainability aren’t compromised. It seems there is still a misunderstanding about the way new and old materials work with each other. Most building materials, including brick, metals, timber, glass and coating systems like paint, are designed and manufactured differently now compared to the way they used to be and therefore they need to be upgraded and maintained differently. This will ensure there are no detrimental effects on the existing building which will undermine its long-term sustainability.

- It is important to understand the virtues and significance of older buildings, and to try to create contemporary interventions that enhance these qualities and don’t overshadow them. Too often this is done unsympathetically, and the old building feels like an obstacle to new signature work. This type of approach will likely be detrimental to the city as it will create competing building forms and poor uniformity.

- Some buildings won’t be suitable for retrofitting and will need to be demolished. However, the existing buildings should be carefully considered before this choice is made. Too often a building of cultural value is removed for something new, because it was decided that the older building wouldn’t provide the required density or meet a new use. Often with better consideration both options would be achieved, resulting in retention of the existing building, its cultural value and the embodied energy within. All this at the same time as creating a sympathetic addition that provides the necessary upgrades required to more than meet the desired outcome.

- Currently in Australia, Green Star is only testing pilot certification for sustainable upgrades to existing buildings. While Green Star does provide a certification tool for new fitouts, it only measures the effects of the new work. By not accounting for the carbon savings in retaining an existing building, with its high embodied energy, it doesn’t provide an accurate measure of how successful these buildings can be.

- The type of existing structure being adapted will often dictate the appropriate form of intervention. A culturally significant building needs to be approached carefully so as not to undermine the significance of its existing fabric. However, a less significant office or factory building may provide scope for far more radical ideas to enhance its virtues. These constraints of working with existing fabric present many exciting design opportunities and outcomes.

The adaptive reuse of our existing heritage is not only nostalgic, but can be economically and environmentally responsible.

Ronan Moss is an architect who works for Riddel Architecture, a practice with twenty-five years’ experience of combining contemporary building interventions with conservation.

Greening the City

Riddel Architecture is working on the sustainable upgrade of a twenty-storey building in Brisbane’s CBD. The 1970s office block is clad in roughcast concrete with a defining grid pattern of windows in deep reveals. While the building isn’t heritage-listed, it is a good example of a building of its age and type and adds cultural value to its surrounding precinct.

The proposal is to wrap a second skin around the building, offset from its facade. This will create opportunities for increased gross floor area, but will also facilitate a range of environmental interventions to increase the building’s energy-efficiency. Importantly, the new building skin will be designed to allow views back to the original roughcast building so as not to diminish its relationship to the history of the city.

Image: Riddel Architecture.

620 Wickham Street

In 1953, architect Karl Langer designed a furniture showroom for his friend Laurie West in Brisbane’s Wickham Street, Fortitude Valley. West’s furniture showroom was a radical example of late modern Australian architecture and featured furniture by international designers such as Eames, Le Corbusier and Marcel Breuer. The building had a series of unique design elements that maximized natural light for the deep building plan, including sloped glazing, concave and elliptical skylight shafts and a serpentine fish pond. In 1963, when West’s showroom ceased trading, the building was converted into a regular shopfront. The original design was unrecognizable.

Recently Riddel Architecture bought the property, aiming to reinstate Langer’s modern architectural gem. During the construction process many of the original materials were revealed behind the newer finishes. By retaining this existing fabric the embodied energy of the building was n0t lost, creating a far more sustainable solution than a new-build project. The restored building, which has been recently finished, provides a unique glance back to Brisbane’s late modern architectural scene. In today’s context, the building still appears futuristic and has provided a way to reactivate the city.

Image: Architecture Australia, January/March, 1954,p.17.

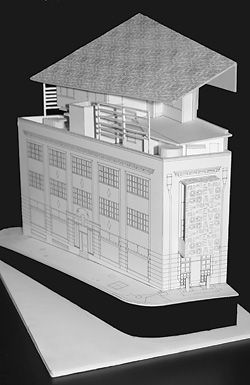

100 Boundary Street

The proposed adaptation of 100 Boundary Street includes a new rooftop apartment with parasol roof supporting photovoltaic panels placed over the existing building. The panels give a generating capacity of 30kw (averaging 150kw per day), which more than meets the energy needs for airconditioning, lighting and general power requirements, with more to spare to sell back to the grid.

The lower roof over the rooms, while shaded by the parasol roof, collects rainwater, which is then held in tanks in the basement, and will be used for clothes washing, water features and gardens on the roof. This modification will attain a better than zero omission status and is intended to be carried out without reducing the heritage qualities of the building.

Image: Model of 100 Boundary Street with proposed additions, Riddel Architecture.

St John’s Cathedral

St John’s Anglican Cathedral in Brisbane is arguably one of the finest of its type in Australia. Recently the eastern view has been revealed from Queen Street, which will soon be blocked for all time by a new eighty-storey tower.

This great opportunity to reveal one of the landmarks of our city has now been lost. Our speculative proposal imagines what one might expect in Rome – the Spanish Steps makes the most of the opportunity.

Image: Rethinking the view to St John’s Cathedral Brisbane, Riddel Architecture.

FURTHER INFORMATION

Riddel Architecture

Specializing in sustainable contemporary architecture and heritage conservation.

W www.rara.net.au

Docomomo

Nonprofit organization for the documentation and conservation of modern movement architecture.

W www.docomomo.com, www.docomomoaustralia.com.au

Centre for Design

Based at RMIT, the centre aims to demonstrate the role of design in achieving an environmentally sustainable future for Australia.

W www.cfd.rmit.edu.au

Green Building Council of Australia

Not-for-profit organization committed to developing a sustainable property industry for Australia.

W www.gbca.org.au, www.worldgbc.org

Your Building

Online Australian resource for sustainable commercial building.

W www.yourbuilding.org/

Sustainable Cities

Database providing knowledge and inspiration on the sustainable planning of cities and best practice cases.

W sustainablecities.dk/

Architecture 2030

A nonprofit organization aiming to transform the building sector from the major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions to a central part of the solution.

W www.architecture2030.org

GreenBlue

Nonprofit institute focusing the expertise of professional communities to create practical solutions, resources and opportunities for implementing sustainability.

W www.greenblue.org

Australian Green Development Forum

Nonprofit coalition that aims to accelerate the adoption of sustainable practices in Australian building and development.

W www.agdf.org.au