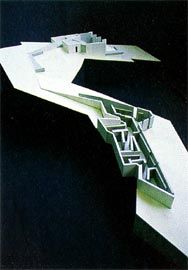

Model of wall, forming the studio and library, in relation to the existing house.

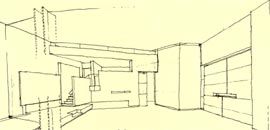

Perspective of the library. The wall cutting into the landscape leads directly to detailed strategies for fabricating workable space.

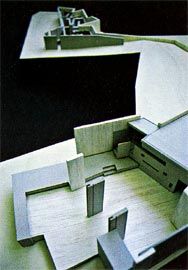

View of the model with library in foregound.

Model with sculpture studio in foreground.

In cinema, the jump-cut introduces ›› temporal disjunction into what should be a ›› unified visual and narrative space. It is a ›› device which shifts attention to the very ›› processes by which visual and narrative ›› continuity may be constructed – or refused.

Such a concept seems apt for reviewing an ›› unbuilt project from Terroir, which exhibits ›› the way in which its design collaboration is ›› constructed.

The project by Gerard Reinmuth, Richard ›› Blythe and Scott Balmforth of Terroir ›› provides a studio and exhibition space for a ›› sculptor, and a library and study for an art ›› critic, on a five acre site 20 km north-east ›› of Canberra. The spaces are situated on a ›› slope below an existing north-facing house.

A meandering wall in the landscape ›› encloses a labyrinth for the library, and ›› directs the outlook from the adjoining study ›› to expansive views in the east. The wall ›› then cuts back into the earth parallel to the ›› existing house, and reemerges folded ›› through the studio, which opens up to the ›› west and to the noise of a natural pool. The ›› direction of the wall’s line is tightened to a ›› radial geometry which extends from the ›› centre of view in the existing house. This ›› radial geometry, derived from Doxiadis’ ›› geometric analysis of the seemingly random ›› topographical distribution of buildings over ›› several ancient Greek sanctuaries, also ›› gives rise to a certain associative and ›› functional naming of the spaces in the ›› project: the library initially proposed as stoa, ›› the existing house as propylaea and the ›› studio as treasury.

The wall is interpolated into furniture ›› elements at each end: bookshelves and ›› writing desk in the library; exhibition ›› platform and thick, operative storage wall in ›› the studio. A notion of defining and detailing ›› building form is skipped here, with a rapid ›› movement from a cutting into the landscape ›› leading directly to questions of fabricating ›› and installing the fittings of workable space.

This movement from gestures conceived ›› at the scale of the site and its greater ›› environs to the pragmatics of furnishing ›› workable space attests to the process ›› through which this design – I do not like the ›› word “evolved” – came to a certain ›› resolution. The office of Terroir exists in ›› three distinct localities. Blythe lives in ›› Launceston, Balmforth in Hobart and ›› Reinmuth in Sydney. This distance meant ›› that the design process was highly ›› mediated. The fax machine and email were ›› utilised throughout the design process, not ›› as form-givers or tropes in an architectural ›› translation, but as facilitators for the very ›› possibility of the three designers working ›› together on one project.

This mediation is visible in the project in ›› two related ways, and here we must take ›› the project not as a supposed building, but ›› as the design process itself. Firstly, there is ›› an increasing level of resolution visible from ›› initial diagrammatical sketches to ›› architectonic model. This rapid forming up ›› of the projects results from the three ›› designers having developed a language, ›› both drawn and spoken, that renders ›› concepts and ideas quite transmissible ›› between them. But secondly, this ›› increasing resolution of the project is visible ›› as a series of jumps or leaps. It is this ›› second feature I am more keen to follow up ›› on in thinking about this project. These are ›› not so much leaps of the imagination or ›› faith, or great leaps forward, but leaps or ›› jumps in the sense of the jump-cut. The ›› project gives a sense that the mediation ›› involves a stitching together of three ›› different perspectives and senses of time in ›› respect of the common project.

The wall is, in some senses, the line of ›› this jumping and cutting. It is its organising ›› structure. It initiated the project, but one ›› gets the sense that it will survive the ›› project as well. It will survive it as the ›› landscape will survive the specific spaces ›› imposed on it, and it will survive the project ›› by becoming the datum, even if only ›› conceptually, for other Terroir projects. The ›› wall maintains a continuity and an ›› openness in the project, the sort of ›› continuity and openness that suggests ›› projected endings are yet to be decided, ›› but have a structure within which to ›› be articulated.

As I cannot – and do not see reason to ›› – determine its adequacy as inhabited ›› architecture, I can only project certain ›› scenarios myself to test the promise of the ›› project. One such scenario, in lieu of my ›› judgement, would be this: the art critic may ›› very well enjoy being lost in his labyrinth, ›› and the sculptor secure with her work in ›› the treasury. The house may provide the ›› prospect, and geometry may govern the ›› relation between these structures. But is ›› there another sense of space, another sort ›› of space that exists between these clients ›› that can transform such a robust set of ›› relations between the structures? This ›› other sense of space would arise through ›› another jumping and cutting, this time by ›› the inhabitants: the introduction of work – ›› with words, with plaster and clay – and ›› objects – books, sculptures – into the ›› spaces, and possibly out of the original ›› places and niches assigned them.

The project has thus reached a ›› sufficient resolution to begin a discussion, ›› and to sustain itself further in the process ›› of being translated into built and ›› inhabited architecture.

Charles Rice is an associate lecturer in

architecture at the University of New

South Wales