In February 2015, I caught up with Santa Monica-based architects Hank Koning and Julie Eizenberg. Remarkably, they still seemed to me the same canny Melbourne architects making clever and responsible architecture that I met thirty years ago as a fresh-faced PhD student. Back then, in 1985, they were working on something that was unusual in Los Angeles: architect-designed affordable housing for families from lower socio-economic backgrounds. They were intent on imparting – with minimal means – design dignity to a series of modest walk-up apartments. They spoke about the importance of spaces between buildings, and about ordinary “people” elements like a balcony, a stoop and a stair where chance meetings might grow into something more meaningful, perhaps even a sense of community.

The two Australians established their practice in 1981 after graduating from the University of California, Los Angeles, where they’d been taught by expatriate Bill Mitchell as well as luminaries Lionel March, George Stiny and Charles Moore. They started their architectural practice in a way that was brave and socially responsible and in response to where work needed to be done. It was a space of practice where frankly others were not prepared to go. And it paid off. Over the next three decades, they developed Koning Eizenberg Architecture (KEA) into a firm of national repute, gaining a succession of American Institute of Architects awards for projects like the Simone Hotel Apartments (1992), the first new Skid Row accommodation facility in Los Angeles in thirty years, and the brilliant and internationally-acclaimed Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh (2005).

The firm’s ability to talk with user groups, social agencies and construction managers, and produce inventive, economically shrewd solutions caught the attention of not just the profession but also educational institutions. Julie Eizenberg has held teaching positions at almost all the Ivy League schools. Her directness, her skill in judging if you like the politics of a commission, and her willingness to champion other women have meant that she is in constant demand. Hank Koning, quietly at her side, is laconic, self-deprecating but equally resilient, even tough. They make an exceptional team. They also bring to American architecture a sense of ethical practice. They’re great admirers, for example, of Alabama’s Rural Studio founded by Samuel Mockbee and currently led by Andrew Freear. They know that part of practice is keeping faith with a local community – and that is what they have done in Santa Monica, where they have lived and worked for the entire time they’ve been in the United States.

The architects reinterpreted the use of stucco, prevalent in local Spanish Colonial Revival houses, in their design of this Santa Monica home.

Image: Eric Staudenmaier

Koning and Eizenberg both graduated from the University of Melbourne (1977), where they counted as important academics like Jeff Turnbull and Graham Brawn, who were positive about the pair leaving Australia, and also the late Evan Walker, for whom Eizenberg had worked while at Jackson and Walker. They admired the lean modernity of Max May’s architecture, were part of the group that formed the Half-Time Club, and part of a talented, oft bumptious student cohort that included Steve Ashton, Howard Raggatt and George Hatzisavas. But their aesthetic and intellectual interests were different then and now. In Los Angeles in the 1980s, it might have been easy to fall under the formalist spell of a Frank Gehry, Morphosis Architects or Eric Owen Moss. In time, Koning and Eizenberg came to know well all of these players, who in turn came to recognize the skill of the antipodean interlopers. Koning and Eizenberg developed a healthy immunity to the vagaries of fashion. They instead focused on an architecture of social relevance that was and has always proved to be not over-earnest or ponderous, but which finds the right balance for homo ludens, always with a deft architectural touch.

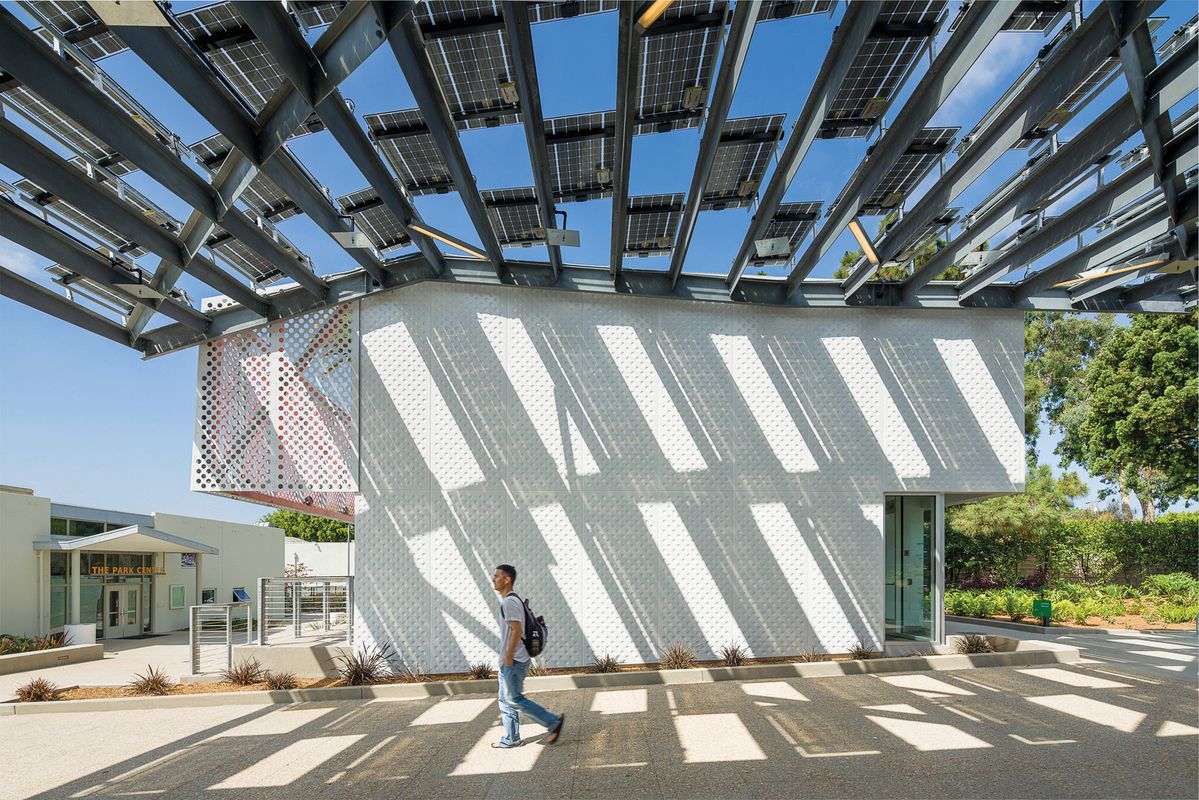

That touch remains with them. On this past visit, I saw four recently completed projects: a library, a school, housing and a house – all in Santa Monica. Each epitomizes the realism embedded in intense engagement with site, client, politics and design. The Pico Branch Public Library (2014) involves not just the creation of a beautifully folded roof over a light and airy reading room but also the melding of new and existing buildings with the 2005 KEA-designed landscape for Virginia Avenue Park (the first US park to achieve LEED certification). Koning Eizenberg Architecture likes the blurring and overlapping of public functions: one day there’ll be a farmers’ market in front of the library’s acid-green fabric canopies, on another it will be families enjoying picnics in the park, playing basketball and throwing Frisbee across the introduced grass mounds. The John Adams Middle School (2013) is a complex combination of refurbishment and addition. A new form of legibility has been introduced to a 1950s school through a smart blend of new structures grafted onto old, splashes of colour and supergraphics, and a series of linear classroom blocks with outdoor teaching spaces and concrete benches supporting solar collectors. Each classroom has a solar chimney – an object that teaches children about the virtues of differential air pressure (and how to avoid airconditioning). These become miniature landmarks across the campus. Silhouette, mini-monuments and the creation of kid places impart a lively new identity.

The Belmar Apartments is a mix of condominiums, artist studios and affordable family housing.

Image: Eric Staudenmaier

A stone’s throw from Santa Monica Beach, the Belmar Apartments (2014) demonstrate Koning Eizenberg’s undeniable skill in making neighbourhoods. Part of an extensive urban development to increase density and a responsible demographic mix, 50 percent of the Belmar Apartments are dedicated to affordable family housing amidst condominiums and artists’ studios. Generously scaled living balconies (big enough for table and chairs) overlook a landscaped “living street,” a community walkway with overhanging wires of night-lights (that recall the washing lines of Italian towns). This “street” connects other urban paths and the development seamlessly knits itself into the city. Compared to the high-end Moore Ruble Yudell-designed apartments nearby, which adopt a soulless developer-led preference for beige and green glass, Koning Eizenberg Architecture’s apartments are fresh, even joyful. They welcome signs of life.

The last project I was shown is a suburban family home (2014): a clever reinterpretation of the stucco language of Santa Monica’s Spanish Colonial Revival houses and strict local planning by-laws, all resolved by the subtle insertion of a series of living landscapes across a gently sloping site. The clients were about to have dinner and were utterly relaxed about our unannounced arrival. The Australian habit of just dropping in did not surprise them in the least.

Aaron Betsky has said of Koning Eizenberg’s buildings that they are “jewels of expressive practicality.” This is true. The work is never overbearing and never precious. But its social value is priceless. In this, it has great appeal. Yet what is concealed here is the extraordinary patience, hard work and multitude of hours of community engagement behind it all. There is a sense of something familiar to us here in Australia: a sort of artless artifice, even architectural humility, that is difficult to register as part of any canon. The work seems utterly natural but we know that it is not: apparent ease has actually been hard fought. As in architecture, as in life, Koning and Eizenberg have not lost their Australian accent.

Source

People

Published online: 14 Sep 2015

Words:

Philip Goad

Images:

Eric Staudenmaier

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2015