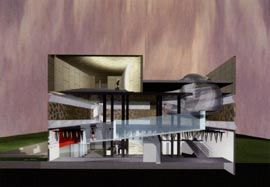

The House of Excess, montaged onto Giorgione’s The Tempest.

Francisco Goya’s 3rd of May, 1808, transformed into a disturbing image of the architect, surrounded by his followers, defending his work.

The architect contemplating his fate, depicted through Casper David Friedrich’s Wanderer Looking over a Sea of Fog, 1815.

SET AGAINST A picturesque backdrop, a tumultuous sky overhead, a man stands somewhat nonchalantly. On his arm, a young woman all long legs and attitude. To his left, another woman with less attitude and more flesh, feeds her baby. Is this the wife? But placed high and glorious behind them all and framed by the landscape, is the house glittering gold. Lo and behold, it is the splendorous architect designed house!

Extravagant, elegant, entirely excessive, too big, too expensive, this is the House of Excess! A glossy domestic monument, a “lifestyle trophy for particular elite groups” to quote architect Shane Murray. And along with the hip city chick, this house has been montaged into Giorgione’s famous painting, The Tempest. In the hands of BNArchitecture, this painting has become a provocative and rather pessimistic statement about the modern architect, his creations and fidelity. A project, I am sure, many will contest. Designed for the recent Melbourne Fashion Festival and exhibited at the RAIA, this project is more precisely a protest from architect Hamish Lyon and firm BNArchitecture (formerly B+N Group) about the lack of debate and of critical discussion that surrounds contemporary architecturally designed housing projects. Lyon is referring to those projects that frequent the pages of architectural magazines, the “beach house”, the “holiday home”, the house that, is rarely accompanied by any kind of rigorous discussion. Those projects, as Lyon puts it, are “quarantined from criticism”, and the architect, the famous domestic architect no less, also escapes critique and evaluation.

The design they have proposed is essentially an appropriation, not quiet a “minestrone” of great moments in modernism. Included are Le Corbusier’s Villa Stein at Garche, Koolhaas’s house near Bordeaux, and a Herzog and De Meuron project. Clad with gold, leopard skin prints and windows made from cut crystal, this house has everything including the standard faddish feature: the “blob”. It has a lumpy bumpy black ceiling, a bunker, a garden you can’t get into, windows you can’t see out of, a runway, a functionless kitchen and more. But it is these ironically glossy images, like the collages of ARM, that become the critical output of this project.

Another image begins with Francisco Goya’s painting 3rd of May, 1808. Here the martyr figure kneeling, arms outstretched but over scaled and colossal, becomes the architect. What was originally a revolutionary but a propagandist image commissioned by the Spanish Monarchy as a protest against the Napoleonic occupation of Madrid in 1814, becomes a disturbing image of the architect surrounded by his followers defending his work, his identity, in short “the ego of the architect”.

Lyons told me that this project is allegorical – the project is designed around a story, albeit fictitious, about an architect and the house he designs for a famous and very wealthy fashion designer. The story goes something like this: an architect was commissioned by a fashion designer to design a house. The House of Excess would be a place for the designer to live and exhibit his work, it had to have runways, space to hold openings and fashion shows and accommodate the champagne slurping people in attendance.

So the house is finished, the designer moves in and all is well until the owner unexpectedly decides to sell the property. The architect, horrified, imagines his wonderful creation purchased by some uncultured capitalist who will ruin the house and alter it beyond recognition. And so in desperation he places himself in huge debt and purchases the house back from the client. But alas the architect’s meagre income prevents him from being able to completely occupy and maintain the property.

Forced to live in one small room in the basement, the architect spends his time in the bunker-like space of the ground floor or staring pensively out of the top floor room window contemplating his fate as depicted by the image using Casper David Friedrich’s epic painting entitled, Wanderer Looking over a Sea of Fog. Completed in 1815, Friedrich’s image shows an inquiring lone figure, withdrawn and contemplating the new world. But for Lyon this man becomes the heroic yet tragic figure of the architect, a voyeuristic man who stares out at a semi-naked woman perched on a cliff and at the world – the world that is indeed the architect’s backdrop.

Used on the cover of Paul Johnson’s The Birth of the Modern, the painting can also be read as a reflection on the emergence of the modern world. For me this raised an interesting issue about contemporary housing. Gaston Bachelard talks about the home as being constructed just as much through our dreams and our thinking as by the very essence of its materiality. The occupant “experiences the house in its reality and its virtuality, by means of thoughts and dreams”. Is it our thoughts and dreams that have gone astray? The problem of contemporary architectural housing and the standard of debate can only be answered through a broader cultural and political discussion. Why is the modern world as we know it in Australia so determined by politeness, by a fear of discussion and analysis? Economics risks suffocating architecture, but so does polite conservatism and a consumerist attitude.We exist in a market place hungry for “lifestyle trophies” rather than buildings addressing some broader social or architectural issue. To make the situation worse, the critic fears speaking openly knowing the responsible architect will be inflamed.

For Lyon, architectural ideas and discourse are disseminated like Chinese whispers in the pub or the corridors of the workplace.

It must be said that one can find examples of housing projects and discussion that are intelligent, sensitive and even optimistic. Melbourne architects Field Consultants and Kerstin Thompson Architects, to name just two firms, produce works that are imaginative, considered and which address issues beyond the envelope of the building. Their work has been discussed in ways that enrich architectural discourse. Murray, writing about Thompson’s Napier Street housing, says her project is “emphatically unconcerned with representing itself as a current lifestyle ‘must have’,” but rather offers an intelligent contextual reading and an “imaginative reconsideration of dwelling configurations”. Similarly Field Consultants’ Holyoake cottage is a wonderful reinterpretation of the small-lot city house. It is a polemic piece of architecture that has much to offer the typology of house.

The fact that these projects are the exception is what BNArchitecture are concerned with, and this is sent up through the House of Excess. American cultural theorist Fredric Jameson claims that everything in the contemporary age is dominated by capitalism and everything in that culture is thus “immediately co-opted into commodities and images”. He argues for a “cognitively viable aesthetics that reinserts the individual in the community”. He believes architecture has a critical role in this because it is in “architecture that modifications in the aesthetic production are most dramatically visible”. BNArchitecture desires the revival of debate about the responsibility of architecture to engage with social issues beyond the idiosyncratic view of the architect. They hope this project will stimulate such a discussion – with such wry and provocatively lush images I am sure it will.

ANNA JOHNSON IS A LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT RMIT UNIVERSITY.