Buildings are simple: a budget, a brief, a roof over your head, and walls to keep the wind out. But of course, our hopes for architecture are like the hopes we have for our children – that they will be better than us, more than us, and, if nothing else, we pray they outlive us. They will take on the world’s joys and cares, and will be called upon to respond, architecture and children alike.

So, it’s not surprising that Angelo Candalepas felt some trepidation in taking on the commission of a new mosque in the western Sydney suburb of Punchbowl. As an architect, he has spoken about the weight of history in religious architecture and, as a practising Greek Orthodox Christian, he does seem an unlikely choice for this commission, at least on the surface. When Candalepas spoke to his then mentor Col Madigan, the older man said, “You wouldn’t give that sort of opportunity up.” Candalepas says, “It was an awakening.”

“There is a present trepidation about entering into the realm of the spiritual. A realm that has a transcending power over us, if fully comprehended,” he writes in Angelo Candalepas: Australian Islamic Mission. “Architecture is one of the arts that can allow a ‘universal’ understanding of emotional experience to form an epiphany.”

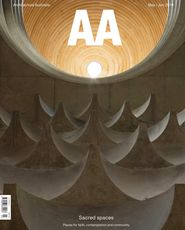

One hundred and two concrete domes, cast in situ, form the muqarnas. A small oculus in each of the domes admits light.

Image: Brett Boardman

There is method in commissioning a respected architect such as Candalepas (or Glenn Murcutt for that matter) to design a mosque. Gaining planning approval for new mosques has revealed some steadfast prejudices and fears. Permission was denied for a new mosque in Currumbin on the Gold Coast on the grounds that it was “too big” following concerted opposition that included vandalism and death threats. In Victoria, Bendigo Mosque was approved despite seventy thousand Facebookers and multiple legal challenges opposing and delaying the project. Pauline Hanson, you won’t be surprised, once called for a ban on the construction of mosques and Islamic schools. Zachariah Matthews, vice-president of Punchbowl’s Australian Islamic Mission, has said that commissioning contemporary design was a response to these known challenges. The mosque is a building to pray in. In a society that so often seems atomized, so often consumed by conflict, so often lonely, to build for prayer seems like a prayer itself.

It has taken more than twenty years to plan, fundraise, commission and deliver the Punchbowl Mosque. The congregation has raised the twelve million dollars needed, an extraordinary testament to the community’s commitment to the project. As director of the Sydney Architecture Festival, Timothy Horton described the project as a “modern architectural masterpiece,” and it was awarded the 2018 Sulman Medal for Public Architecture. It isn’t even finished yet.

Inside, the main prayer space appears to have been sculpted from raw concrete. The large dome draws the eye up, magnifying the spiritual significance of the space.

Image: Brett Boardman

The brief called for a three-hundred-year lifespan; the architect proposed a thousand. In an age of catastrophic cheapskates, contract law and fast-tracking, this is more than hyperbole – it represents a kind of resistance. For Candalepas, concrete is the material of the ages. It has an almost transcendental significance. The Punchbowl Mosque is almost entirely cast in situ – like an ancient building, it appears sculpted as from raw material. There are few visible services, and heating and cooling is subsumed in the slab. The balance of permanent form and provisional mechanization is tipped toward the pre-industrial.

Candalepas has designed a complex that includes a two-level underground car park and a primary school, or madrasa – a type that evolved from the mosque to become the second most important religious building in Islamic tradition. The school, when built, will address the street and return to form a central courtyard. The mosque holds the rear corner of the site and is approached through a low portal in the street wall. Passing through, the mosque is before us, across a forecourt with a covered walkway to the right. To our left and pushing obliquely forward is a contemporary take on the minaret. My guide calls it “an Australian minaret” – no longer amplifying the call to prayer, it is more outcrop than campanile. It is no taller than the building and screened, open to the breeze. Its purpose is not for the muezzin to perform the call to prayer over the suburbs, but to house the women’s separate entry, ritual washroom and prayer gallery. In Candalepas’s arrangement, the women of the congregation now occupy a place traditionally reserved for men.

The entry to the women’s prayer gallery, accessed via the minaret.

Image: Brett Boardman

The separation of men and women in Muslim spaces has its roots in Ottoman Islam and has become a global typological norm. To many of us in secular Australia, it will seem incongruous and, indeed, there is debate within the Muslim community as to the future of this tradition.

The men will turn right into a long washroom. They will perform a ritual washing, the wudu, which is accommodated in a utilitarian space but also one tuned for spiritual preparation. Indirect light creates a cool calm; timber and tile complement the concrete. It is tactile but unfussy. The men will return to the covered walk and then to the wide timber doors leading to the prayer hall proper. The entry is low, compressed to the height of the doors through which the domed hall opens around the prayerful. The sequence from street to prayer is an essay in the compression and release of space.

Prayer is one of the Five Pillars of Islamic faith. Prayer is a duty, a practice and a spiritual act of worship. The faithful must answer the call to prayer five times a day – facing Mecca, standing in intimate proximity, they will bow at the waist, prostrate themselves on seven bones, forehead to the floor. With each posture, appropriate prayers are recited, the physical ritual aligned with the spiritual offering. Prayer as powerful discipline.

A central dome sits over all, with a concrete ring beam cast on site. A thin band of clerestory windows floats the dome; a circle sitting over a square. In Islamic architecture, the laws of proportion are based on the division of a circle inscribed by regular figures – the circle is the clear symbol of the Unity of Being (wahdat al-wujud) that contains within itself all the possibilities of existence, as described by Titus Burckhardt in Mirror of the Intellect: Essays on Traditional Science and Sacred Art. For Candalepas, the circle is “an abstraction of all things found in the universe,” but it is the muqarnas that really makes the heart sing.

A timber screen physically and visually separates the women’s prayer gallery.

Image: Brett Boardman

In traditional Islamic architecture, muqarnas is applied ornamental squinches repeated in crystalline exuberance. In Punchbowl, as elsewhere, the squinches are deployed to negotiate the transition from circle to square. The Topkapi Scroll, dating from fifteenth-century Iran, contains some of the earliest pattern drawings for muqarnas, which has no intrinsic boundary or scale but can be repeated and scaled at will. In this, the muqarnas reminds me of Madigan’s tetrahedral grids, which he extended in drawings and on site, creating vectors and vertices to order the world around his buildings.

Candalepas’s muqarnas is not applied but cast in situ, a single pour making it structural ornament. They recall the coffered concrete dome of the Pantheon and the cascading domes of Istanbul’s Blue Mosque, but the chief sensation is not of historical recollection but of originality. Their presence, unadvertised and unexpected on arrival, seem like a cast taken from the vault of heaven.

Above the large prayer space, the women’s prayer gallery is accessed via the minaret. The women are raised, almost level with the domed muqarnas; a timber screen provides physical and visual separation between men and women. Over two levels, the women look down to the men on one side and out to the courtyard on the other. In the prayer hall, the timber is modest and warm, and complements the concrete forms. However, on the reverse side – the women’s side – the steel frame and bracing are expressed, resulting in a harder, unfortunate mechanical articulation.

In plan, the screen appears as a sharp chamfered slice across the incomplete square of the prayer hall. This line is the clearest disruption to an otherwise orthogonal armature, aligning the prayerful to Mecca. It is an intriguing gesture that seems to render the screen between genders a tense provisional element. It is as if, being timber, it might be the first thing to perish in this thousand-year building.

The rituals of worship have informed the organization of space. The male ablutions room is a utilitarian space, but also one tuned for spiritual preparation.

Image: Brett Boardman

There are one hundred and two domes in all, and ninety-nine will receive calligraphic ornament. Each will be unique, inscribed with one of Allah’s ninety-nine names and the hilya, an ornamental calligraphy that describes the qualities of the Prophet. Craftsmen from Turkey and Iran have been commissioned to paint the inscriptions directly onto the concrete. The Prophet said, “Allah has ninety-nine Names, one-hundred less one; and he who memorized them all by heart will enter Paradise.”

The Most Merciful, the Giver of Peace, the Shaper, the Provider, the Giver of Honour, the Giver of Disgrace, the Giver of Life, the Bringer of Death, the Finder, the Indivisible, the First, the Last, the Timeless. Perhaps it seems indulgent to list even these few here, but the naming of Allah in this space will have a profound effect on the sensation of the room as if through nomenclature the faithful might be brought into his presence.

This kind of text and ornament is anathema to so much of modern architecture, an edict that sometimes seems dogmatic. These two crafts, architecture and calligraphy, are the highest orders of art in Islam. How rich the potential to communicate another sensation, another meaning, another hope beyond utility. Even as Islam, an aniconic religion, proscribes the depiction of sentient beings – God, people and animals – it has led to the development of a complex geometric and calligraphic art and architecture. The proscription isn’t a limitation on invention, but its foil.

Burckhardt describes the role of aniconism in Islamic art:

Islamic art as a whole aims at creating an ambience which helps man to realize his primordial dignity; it therefore avoids everything that could be an ‘idol’. […] Nothing must stand between man and the invisible presence of God. Thus Islamic art creates a void; it eliminates in fact all the turmoil and passionate suggestions of the world, and in their stead creates an order that expresses equilibrium, serenity and peace.

The apparent incongruity between Islamic tradition, Candalepas’s modernity and his Greek Orthodox heritage is resolved into an original, propositional whole, at once traditional and contemporary. Punchbowl Mosque takes on the world’s joys and cares, and it responds. It will certainly outlive us all.

Credits

- Project

- Punchbowl Mosque

- Architect

- Candalepas Associates

Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Project Team

- Angelo Candalepas (director); Adrian Curtin (senior associate); Evan Pearson (principal); Jeremy Loblay, Rachel Yabsley, David Butler, Ivan Jeldrez, Claudia Takada (architectural team); Alex Dircks, Andrew Scott, Christian Natterodt, Clancy Mears,, David Tordoff, Nichole Darke (architectural team – early stages design and documentation);

- Consultants

-

Access consultant

Accessibility Solutions

Acoustic consultant Marshall Day Acoustics

BCA and PCA Blackett Maguire and Goldsmith

Builder Infinity Constructions

Fire consultant Innova Services

Geotechnical consultants JK Geotechnics

Hydraulic, mechanical and electrical engineer Jones Nicholson

Landscape architect Taylor Brammer Landscape Architects

Planner SJB Planning

Quantity surveyor Napier and Blackeley

Stormwater consultant Neil Lowry and Associates

Structural engineer aylor Thomson Whitting, Wood and Grieve Engineers

Surveyor Geometra Consulting

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Public / cultural

Type Religious

Source

Project

Published online: 24 Jul 2019

Words:

Mark Raggatt

Images:

Brett Boardman

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2019