Jury Citation

Olympic Pool Competition,1956, James Birrell with Rudi Krastins and John Rawlston. Neville Ward, the other team member, is behind the camera. Image: John Macarthur.

Captain Birrell, 1967. Image: John Macarthur.

In Papua New Guinea, circa 1964. Image: John Macarthur.

Throughout his career of over fifty years in public and private practice, James Birrell has made a spirited and distinguished contribution to the discipline of architecture through his built work, through his publications and through his service to the profession and the wider community.

He is best known for the buildings that came early in his career, following his appointment in 1955 as the City Architect for the Brisbane City Council and later, in 1961, as the Staff Architect for the University of Queensland. His education and early practice in Melbourne fostered an enthusiasm for abstraction, expression and inventive construction, all of which register in his major projects of the period. These include the Centenary Swimming Pools, the Wickham Terrace Carpark and the Toowong Library for the Brisbane City Council; Union College, the J.D. Story Administration Building, and the Agriculture and Entomology Building for the University of Queensland; and the library for James Cook University in Townsville.

Each of these buildings is shaped by a separate exploration of the significance of form, yet they share an aesthetic governed by tectonics, material and structure. Looking back, it is hard to appreciate how few precedents there were to draw on as Brisbane emerged from the material and fiscal shortages of the postwar era. Birrell’s architecture catalysed a fresh appreciation of the possibilities for designing public and institutional buildings in ways that embraced both innovation in construction and the pragmatic constraints of budget, site and climate. Over time, his office provided the training ground for a bevy of highly regarded architects including Rex Addison, Bruce Goodsir, Russell Hall, Helen Josephson, John Railton and Don Watson. The potency of Birrell’s architecture is such that these early buildings continue to provide inspiration for many of Queensland’s younger practices that, in turn, are gaining national and international recognition.

Following this period of public practice, Birrell established his own practice in 1967 with projects in Papua New Guinea and regional Queensland. His later work included large-scale planning schemes for the Government of Indonesia and the World Bank, among others. His most significant publication is the biography of Walter Burley Griffin, which resulted from his award of the 1961 Sisalkraft Travelling Scholarship. Fittingly, he currently serves on the committee for the Griffin Legacy in Canberra.

He was the co-founder of Architecture and Arts in 1951 and has written at length about architecture and planning. He co-edited the book Building Queensland for the Queensland Chapter of the RAIA, published in 1959, which remains one of the few inclusive records of the architecture of the day. Recently, he spent four years as a member of the National Capital Authority and chaired the Parliamentary Precinct review.

As an architect whose work has made a significant contribution to the quality of the built environment in Australia and continues to inspire, James Birrell has had a formative and enduring influence on the architectural profession and is a fitting recipient of the 2005 RAIA Gold Medal.

Michael Keniger, for the RAIA God Medal Jury.

The 2005 jury comprised Warren Kerr, David Parken, Greg Burgess, Louise Cox and Michael Keniger.

JAMES BIRRELL IN CONVERSATION WITH JOHN MACARTHUR

James Birrell, December 2004. Image: John Macarthur.

Opening of the Toowong Library, from the album “Toowong Municipal Library Official Opening 14 April 1961 by Lord Mayor T.R. Groom”. Image: John Cocker, Brisbane City Council Photographer.

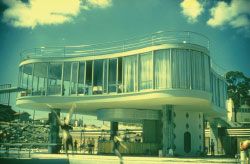

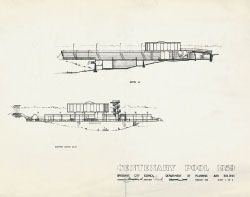

Centenary Swimming Pools, Spring Hill, Brisbane, 1957–1959. Images: John Cocker, Brisbane City Council Photographer.

Toowong Library, Brisbane, 1959. Image: James Birrell.

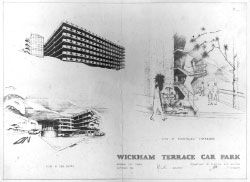

Wickham Terrace Carpark, Brisbane, 1958–1961. Image: John Cocker, Brisbane City Council Photographer.

Wickham Terrace Carpark, Brisbane 1958–1961.

Annerley Library, Brisbane, 1957.

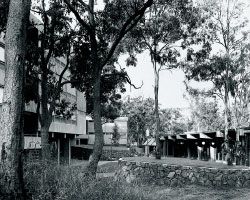

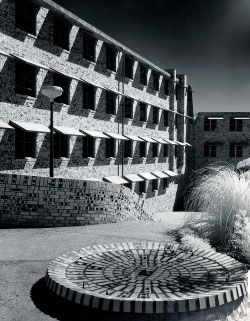

Union College, University of Queensland, 1963–1972. Image: David Knell.

Union College, University of Queensland, 1963–1972. Images: Richard Stringer.

John MacArthur Jim, you’ve often said what a great inspiration Walter Burley Griffin has been to you. Your book has been important in Griffin scholarship [Walter Burley Griffin, UQP, 1964]. Did you know about Griffin growing up in Melbourne? Or was his work introduced to you at university? Did he have a reputation among your generation of students?

James Birrell Well, in a way I knew about Griffin before I knew of architecture. When I was a kid I went to Essendon High School, which had its sports field down on the banks of the Maribyrnong where Burley Griffin’s incinerator was. I didn’t know anything about Griffin but I knew the incinerator was a fascinating backdrop and the sports fields had been built on the ash that had come out of the incinerator. That was my first real feel for any magic that came out of architecture. At the same time my father used to take the family out to the cinemas in Melbourne, and the cinema that fascinated me more than anything was the Capitol Theatre; you used the architecture. You would go in and there was a superb interior, the roof would light up with the stars in the sky and it was a great outing regardless of the movie you saw. My grandmother lived in Carlton and I used to walk from her place along the full frontage of Newman College, which also looked different. And my grandfather in his old age was the lift driver in Leonard House where I caught the tram. So I had a subconscious exposure to Burley Griffin before I even considered being an architect.

The architects were discovering him when I was at uni. Boyd did a lot of work on the rediscovery of Griffin. He didn’t do it as well as he could’ve done, but he knew there was a great man involved and he didn’t want to miss out on it. I really began to think about Griffin when, after graduating, the Commonwealth Works Department sent me to Canberra in 1952. Griffin had been denigrated terribly from 1922 on. His contract had run out and it wasn’t renewed. Sulman was appointed in his place as chairman of the new Federal Advisory Council and Griffin was asked to work with him. Sulman had started to undermine him before Griffin’s ship arrived in Sydney, and Griffin said, “I can’t work with this man”. It was Sulman who made the statement that did the most damage to Canberra, and that was: “Griffin’s idea of people living on boulevards and walking up and down footpaths was a Continental idea; we would stick with the British where people will have their own backyards and they won’t be walking down the street.” So he converted the whole plan to English garden city rather than a city in its own right.

In Canberra I lived in hostel accommodation for the first few months, because Bob Menzies was moving the entire public service there and housing was in very short supply. I used to sit around communal tables with diplomats and other interesting people sharing these hostels, and we’d have fine debates. I used to harp on about Burley Griffin and what was going wrong with Canberra and they used to say, “if you think this seriously, Birrell, write a bloody book about it”. When I finally got access to the Parliamentary Library I saw that the Griffin files had not been opened since 1922. They were covered in cobwebs – all those beautiful drawings of Marion Mahoney’s were there with beetles running over them. Even at that late stage they were siting buildings across avenues just to make sure Griffin’s plan couldn’t happen because it was American. Anyway, I still get wound up about Canberra …

JM So was it Griffin and Canberra that lead you to be interested in planning? How did you come to broaden your practice and register as a planner?

JB Deciding to qualify as a planner came a little later and out of a lot of reading. I used to read Louis Mumford, the American academic, and Frederick Gibberd, who did all those British New Towns. I later met Gibberd, when I was on the Sisalkraft Scholarship, and got on well with him. He had a fantastic collection of Australian watercolours. That was his hobby. It seemed to me that no-one took an interest in planning in those days. The University of Queensland was a case in point. Before I took the job as University Architect [1961], they were simply carving building blocks from the site as if it was a suburban subdivision. I started to say, “You don’t do that; let’s rub off all the subdivision lines and let’s start to design buildings on sight lines into the landscape”. This was revolutionary. Griffin must have had some effect on that. At the University of Melbourne I had taken a course on Fine Art from the fifteenth century on, and this introduced me to Renaissance gardens, and that led onto Capability Brown and Olmstead. Anyway, this interest in the context of building fascinated me, so when I was Brisbane City Architect I contacted the Planning Institute. In Brisbane City Hall I sat the exams set by the University of Sydney as an external applicant. I actually failed the design exam the first year, because I didn’t know the site and I misread the bloody scale! But I got through the next time and suddenly the planners loved me because there were so few of us in Queensland. There were people like Alex Yates trying to get Toowoomba on the road. We all formed a little group and kept the Planning Institute of Queensland rolling along; we started Queensland Planner and things like that. I think that’s a role an architect should take and I think it is sad that the institute of planners has been taken over by non-architects, development-controllers with almost no design training. All the campus planning came out of this. After reorganizing UQ, I did a scheme for Griffith Uni at Nathan, then James Cook at Townsville, and Port Moresby and Lae.

JM You took up the job with Brisbane City in 1954 and left in ’61, having done some hundreds of buildings. These were mostly small and mostly good, but among them are the Wickham Terrace Carpark and the Centenary Pools, which were big-budget projects that were popular and critical successes nationally. How did you manage it?

JB In Darwin I was in charge of a drawing office at a tender age, and I learnt a great deal about how to run a big general practice, and especially about how to deal with bureaucracy. In the Darwin Office most staff were afraid of files, they’d write something and pass it on to someone else. You would get to the end of the financial year and dozens of departments had not spent their building allocations. So I just went round to see the chief, saying “Do you want to fix up this problem or that?” and I’d have a design all ready so they could get the money committed before it disappeared into the next budget.

Brisbane was still in a mess from the war as late as 1954. Nobody had painted anything; the City Hall leaked like a sieve; you’d get a burst of rain and manholes would jump up with cockroaches crawling out. The place had kind of given up. Well, Groom got in as mayor and said, “Let’s smarten the place up”. He had supported this cultural shift and built Brisbane into this nice place where there were nice things for the people. There’s a picture here. That’s the photo of the opening of Toowong Library. See the people in the street? That tells a story that the people of Brisbane were at a stage where it was important to give them pride.

When Clem Jones came in as mayor, his idea was to sewer the place and I could see that any budgets for building would disappear. They had already started to disappear six months before the election and I was sitting there twiddling my thumbs. As far as I can see, any buildings Jones had built had no architecture; the whole idea was to denigrate the architecture. So I took the job as University Architect. I am bloody glad I didn’t stay with the council.

JM So many of those buildings, even the small ones, are very memorable. Some, like Toowong Pool, look as if you are following your teacher Roy Grounds’ idea of civic architecture being about “significant form”. Was this your method on these smaller suburban libraries and swimming pools, toilet blocks and so on?

JB I think I was a bit more collective than Grounds. He would have a fixed idea and go for it. With the Centenary Pools, the concept of the curvy form and burying all the mechanical equipment under the ground so you didn’t see it was pretty organic. I think also I was never scared of overwhelming landscape. Most architects want to see their buildings, but I think the entire environment is what it’s all about. For instance, at the Pools the thing that struck me straight away was that you could take a sight line across the valley through the front door of the Medical School half a mile off. It looked in the distance like a piece of Capability Brown landscape, and I was always a sucker for the English landscape school. Probably the best thing that came out of England was the parks and gardens.

JM So what are your favourite buildings from the BCC period?

JB The Toowong Library and the Centenary Pools were interesting, so were Annerley Library and the Wickham Terrace Carpark.

JM Speaking of Roy Grounds, you were much more inspired by his teaching than that of Robin Boyd. These days their reputations are rather the other way around.

JB That’s because Robin Boyd was a publicist and Grounds wasn’t. I suppose you have seen the book Robin Boyd: A life by Searle? You try and find Robin Boyd in the book. I won’t say any more about Boyd, but Grounds …

Melbourne University had just recommenced after the war. We were the first students under Brian Lewis. He got around him some incredible tutors – Roy Grounds, Ray Berg, John Mockeridge, Fred Romberg – and then they got a guy direct from the Bauhaus called Fritz Janeba. He came a year after me but affected everybody else. All the contemporary people who grew up under the influence of Roy Grounds – his influence was incredible. But I found out an interesting thing about Grounds about that time … In the works department where I worked there were a lot of old men because the war had depleted all the young men; they were brought in from retirement to do military work. There were two I remember more than the others. Their names were Stan Garrett and Hugh Craig. They were from the Blacket office and were steeped in Georgian architecture, and a lot of their work had been in alterations, extensions and improvements to old colonial architecture. And they claimed to have trained Grounds when he was a journeyman in architecture. They said, “Oh, you’re always worshipping Grounds but we don’t think you understand him – he’s not the Modern architect you think he is, he is much more than that, he’s Georgian. Next time you are worshipping Roy Grounds’ buildings, half close your eyes and look at it fuzzy and you will see a Georgian building”. And it is true, he was steeped in the geometry and proportional systems, so that was an incredible influence to get. If you look at the Academy of Science in Canberra, it’s a pure piece of Georgian geometry.

JM Grounds’ experiences would have been typical, then, of many Modernist architects of that generation. Do you think Modernism requires that kind of background history to react against? Or that continuity of skills?

JB Absolutely, but the schism comes later with postmodernism. Modernists might not fully understand the classical aspects of what they are doing, but postmodernists are at one more remove. They are reacting against something they don’t understand – they are mannerists. Everybody who works under the influence of people like Grounds and, if you extend it, people like Le Corbusier, are working with influences that came out of the Beaux-Arts. They had a foundation in Georgian or classical design, and even though they reacted violently they knew what they were reacting against.

JM Yes, but what about yourself? You didn’t have this training. You observed it through Grounds. And some of your work is very aformal, as we’ve discussed specific to the topography, and if there are geometry or proportional systems there, they aren’t pitched in the same way as Grounds so that the geometry hits you straight up …

JB I was on the tail end. Other influences come into play. You see, we were remote from the sources. Australia was a long way from England (particularly in the war) and the blokes that really got the experience were the remnants of the troops that came back. They had seen it in the flesh.

JM What about English Modernism? Some of Brian Lewis’s buildings, such as University House in Canberra, have much more the flavour of the asymmetrical picturesque-inspired Modernism that The Architectural Review was promoting from the late 1940s.

JB English Modernism had a big role. I was just about to come to that, you’re reading my mind … What happened was that because of our remoteness we were very dependent on imported books from England. The Architectural Review was very important. It had been taken over by Pevsner and Richards; they were very European. And we would pour over it because it was the only thing you could get. But it was British art as much as architecture that interested me. There was a woman, Miss Livingstone, one of our drawing office supervisors in the Technical College. She stood around and helped you with your freehand design. A middle-aged, very sensitive woman, she’d been a friend of the English Modern artist Ben Nicholson. So she had brought all these books from England and she had a bookshop called Primrose Pottery Shop down in Flinders Lane. It was the only place where you could get anything modern at all. She used to cut the books up so you could buy them by the page. We used to save our pennies and buy a Henry Moore page. So a lot of my interest in the relation of texture and form was derived from the exposure through her to people like Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth. In that other book on my work you talk about some brickwork with the weeping mortar as being Brutalist, but I thought of it in tactile terms of Hepworth and Nicholson.

JM So for you Modernism isn’t simply a matter of architecture, it is something we see through other arts?

JB For me the arts are all interrelated. I did Fine Arts at Melbourne University under the instruction of Lewis. He couldn’t put me straight into fourth year without claiming he had an influence on me. So he said you better do third-year Fine Arts, which was the fifteenth century in Europe, which bored the living daylights out of me but I enjoyed it in the finish. A lot of the development of Renaissance architecture in Italy was predicted by painters before the architects got a chance. Massaccio, for instance – he draws lots of things that come out in Michelangelo’s architecture and there is a good reason for this. None of those blokes ever saw the buildings finished because they took a hundred years or so to do, so there was a tremendous influence between the two and quite often you cannot draw a line. It irritates me, this legislating to have art in architecture and the government requiring that so-many-percent of the project go into what is allegedly a piece of art, which is stuck to the building. This is not the way it’s done at all, for me. As a consequence we were always busting to get something done and the best and quickest way was to get involved with the artists, because you could get some ideas of proportion or texture across with your associations with them, you had a common interest. I was part of the reformation of the Contemporary Arts Society of Melbourne and had a lot of friends among them; we used to have coffee and chat and I entered some of their exhibitions. So I am a little disturbed when I walk down the mall here and see some sculpture hung up on wires, which is supposed to be art integrating with architecture – it’s stuck on!

JM You’ve had a very large influence on architecture in Queensland, even just through the people who’ve worked in your office, who’ve all gone on to do quite different work. Some who spring to mind are: John Kershaw, David Cheesman, Don Watson, Bruce Goodsir, Rex Addison, Russell Hall. When I was a student Bruce Goodsir was my tutor and he got me to look at the Agriculture Building at uni, which he worked on for you. It was very unfashionable in 1980! You weren’t frightened of giving them a fair bit of responsibility?

JB Well, it is what you have to do. I don’t understand these architects who claim to do it all themselves. The animosity that was in some offices over who designed what … in one place I remember they used to redraw drawings to get their initials on them. I found that people who were doing a course and were enthusiastic about architecture made far better staff than trained architects. There is no question they were eager to find something out, achieve something and follow a pattern. My technique was: I would start work at sunrise, say 4.30/5 in the morning, then I would go around all the drawing boards and draw all over their boards and they thought I had worked all night. About 1 P.M. I would do all my office work, then I would go out for a long lunch, then I would come back about 4 P.M. and give them heaps and make sure they had done a good job. You have to be on their boards all the time. I cannot understand all the people who work with computers. I mean, computers can do things that you couldn’t have done in the past, but you need your intellectual shorthand connection with your staff, I think. Even with an arthritic hand I can still draw something and get what is up in the mind on paper and expect the staff to work with it. And every one of those people responded to that through the office.

It’s a matter of philosophy. Sometimes I was too gentle and things went through because I didn’t want to hurt someone’s feelings, but it didn’t happen very often. Roy Grounds, he was a bastard, I did a beautiful set of drawings … He had a dairy farm and he used to set some of the university projects for the sheds for the dairy farm. I designed a milking shed with these tanks on beautiful single-column stands that you could mow right around. At the time that great movie had been made, My Fair Lady with the famous line in it – Grounds comes in and puts his great crayon across my drawing and says “not bloody likely”.

Dr John MacArthur is a reader in architecture at the University of Queensland. With Andrew Wilson, he edited Birrell: Work From the Office of James Birrell (Melbourne: NMBW Publications, 1997). This is an edited transcript of an interview conducted on 23 December 2004.

TEN TRIBUTES TO BIRRELL

Staff Club, University of Queensland, 1963. Image: James Birrell.

Agriculture and Entomology Building, University of Queensland, 1966–69 (later named the Hartley Teakle Building). Image: Richard Stringer.

J. D. Story Administration Building, University of Queensland, 1963. Image: University of Queensland photographer.

Resource Materials Centre, Darling Downs Institute of Advanced Education, 1975. Image: Richard Stringer.

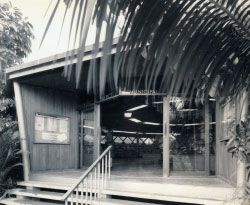

Arts/Law Building, University of Papua New Guinea, circa 1969–1974.

Papua New Guinea Banking Corporation Headquarters, Port Moresby, 1977.

Papua New Guinea Development Bank Headquarters, 1977.

Maroochy Shire Chambers, Nambour, 1978.

Jim Birrell is an extremely noteworthy Australian architect, town planner, historian, author, public figure and liver of life to the full. From the early 1950s to the present day he has been sharply imprinting himself on those disciplines, as well as on the hearts and minds of his friends, lovers, family members, colleagues, business associates, coworkers, clients, readers, fellow municipal councillors and board members, even his detractors, and, above all, those who have occupied or merely gazed upon his extensive body of work, studding the cities, towns, campuses, coastlines and interior regions of Australia, Papua New Guinea and beyond. The reality was that in raw, post-World-War-II, British-dominated Australia, the difficult task of achieving a much-needed national culture in the arts, particularly architecture, was necessarily going to be in the hands of intelligent, talented risk-takers. Mere scholarship and diligence weren’t enough. Those cultural pioneers also needed to be well read, lateral-thinking, understanding of both the prevailing Beaux-Arts school and the avant-garde, aware of how to beat the establishment at its own game, able to suss out the bureaucracy and the property industry, and, above all, able to get things done with apparent calm. As well, it didn’t help if they were uncharismatic, hated attractive members of the opposite sex and a drink, possessed no ego or mood swings whatsoever, or were humourless, timid, prosaic or void of common-touch charm. Enter the slightly non-saintly J. P. Birrell to tackle the cultural cringe hands-on. It was a labour of love for this proud social outsider, performed beguilingly with legitimate references to the works of the masters of world architecture, town planning and landscape design – the disciplines then lagging behind the other Australian visual arts, to which he remains so well connected, and which he has always so brilliantly and unself-consciously incorporated into his work. No boring over-achiever, nor obsessive megalomaniac, our Jim. Still working in his seventies but semi-retired these days. He could intimidate and be dismissive, and always demanded intellectual and technical rigour, usually tested against his own not inconsiderable knowledge and talent, modestly invoked. But he could definitely inspire and knew how to get the best from everyone working with him. Actually, he depended, even relied on their input, but invariably acknowledged their contributions. He remained the boss, an ego who could still take responsibility if things went wrong.

We are told by the American Institute of Architects that the profession of architecture is changing from being what architects do to what architects know. Is that an expression of acuity in the age of managerialism, or a dangerous and irresponsible surrender to a (hopefully transient) doctrine?

Examine the works of a truly complete architect, Jim Birrell, and find out.

JACK KERSHAW B. ARCH. FRAIA

The year 1959 was a milestone for Queensland. It was the state’s centenary, celebrated in Brisbane with a new swimming pool designed by James Birrell. As City Architect, Birrell’s work from 1955 enlivened the city. For a back-seat passenger like myself, his public toilets and maintenance sheds and later his libraries at Chermside, Annerley and Toowong were childhood landmarks with an urbane sophistication in a determinedly suburban city.

1959 was also a big year for me – a spine fusion kept me from the last six months of my primary schooling and I did the scholarship examination at home encased in a body plaster. To celebrate, and as my first outing for five months, the family had dinner at the recently opened restaurant which hovered over Birrell’s Centenary Swimming Pools. My siblings jumped from the three-metre diving board while I, still immobilized, admired the architecture. There was a lot to see – Birrell’s unerring topographical opportunism, the weir-like pool deck, the structural gymnastics, the patterned materials and the futurist restaurant (inappropriately Chinese). In the following year, my regular check-ups were on Wickham Terrace. Under construction opposite was the municipal car park, Birrell’s next masterpiece and similarly unprecedented: its entry a freeway flyover; the corkscrew ramps unwinding from the steeply raking hillside, their upward trajectory restrained by thickly coiled cadmium springs; the cantilever stairs (like most of Birrell’s borrowing, better than the original); and bumpers appropriate for a Studebaker. But by then Birrell had moved to the University of Queensland where he successfully redressed, for the short time he was there, the pragmatic undoing of Hennessy’s powerful master plan. This almost terminal activity resumed after Birrell’s resignation in 1966 – a not-too-different story from both his council and university masterworks. The J.D. Story Administration Building, the Agriculture and Entomology Building and Union College are all to a greater or lesser extent now diminished by pragmatic maintenance. Despite the recent heritage listing of the last, Brisbane still has a way to go in recognizing and caring for its architectural achievements. In his council and university days Birrell received less official recognition both locally and nationally than he deserved. The award of the RAIA Gold Medal redresses this oversight.

DON WATSON

In a climate in which most figurehead Australian architects are hesitant to provide opinion, Jim Birrell offers stark contrast. To honour Birrell’s contribution to architecture is to honour critical practice. With the aim of promoting and advancing the profession and its contribution to the arts, Birrell has, to his credit, never sacrificed dissidence for decorum. He has spoken and continues to speak critically about architecture in person. He also criticizes its conventions through his built works, the well-known of which he produced in his early career. In this regard, and to use just one iconic example, I refer to his Agriculture and Entomology Building at the University of Queensland (1966–1969). Built unashamedly of brick seconds, mortar is left dribbling from its joints, not caring to clean itself up, and by its disregard revealing another form of beauty. It is Birrell’s refusal to accept aesthetic sobriety, to succumb to style, and his pursuit of experimentation with architectural form, texture and construction that marks his seminal contribution to Australian architecture.

IGEA TROIANI

At the dinner held at the Staff Club at the University of Queensland after the launch of the publication Birrell:Work from the Office of James Birrell, in 1997, I remember joking with Jim about the square table we were dining at in one of his circular rooms. He proceeded to tell me his ambition for the room. It had been conceived, he said, as a room where academics from different disciplines might meet and talk, to facilitate discussion and collaboration across the disciplines, a significant new locus in the university. In his original conception there was no furniture in the room except for a cushioned seat around the perimeter, with beer taps connected to kegs in the bar below at one location, and a mattress as the floor so that academics might pull their own beer as a way of lubricating the discussion and use the floor to recover after a particularly intense exchange. Jim’s conception of the Staff Club exceeded its social function. Needless to say the Senate didn’t approve his idea and the room had ended up containing the square dining table we were seated at. This story, while humorous, has at its heart the broad ambition that makes Jim’s work so engaging: architecture as culture (see John Macarthur’s preface to Birrell:Work from the Office of James Birrell).

ANDREW WILSON

I first met James Birrell around 1950 and remember him as a fun loving but serious fellow student at the University of Melbourne School of Architecture. In 1951 I became editor of the Victorian Architecture Students Society news-sheet Smudges, originally founded by Robin Boyd and Roy Simpson. In 1952, sensing the need for a broader forum dedicated to the cause of modern art and architecture, I and my student friends Helen O’Donnell and James Birrell persuaded the other Smudges board members that the news-sheet should be wound up and replaced by a national journal. This became the magazine Architecture and Arts. I designed and edited only five issues before being replaced in unfortunate circumstances, but the journal continued to document, promote and critique Australian modern architecture and art until 1968. Jim contributed a number of significant articles during my editorial tenure. After graduation, Jim worked for a while in Melbourne, then moved to Canberra and later Darwin. In Canberra, I recall Jim designing some amateur theatre sets for a local repertory group and he asked me up to stay with him and see the show. I did and Jim exhibited some of my Canberra sketches in the foyer of the playhouse. Jim wrote me many letters over the years. He wrote of his frustrations and achievements. Such is the pattern of life. I lost track of Jim, to some degree, when he moved to Brisbane, although in 1964, when the University of Queensland Architecture Students Society asked me up to deliver an evening public lecture, Jim kindly put me up at his home in St Lucia and even took me to the beach at Maroochydore. We were all starting out in architecture then. A lot was happening – there were struggles to survive in private practice and to convince clients of the merits of our architectural offerings and philosophies. Jim, of course, went on to be Brisbane City Architect and University of Queensland Architect and to create the works for which he is recognized today. I congratulate Jim on his achievements and particularly for his 2005 RAIA Gold Medal Award.

PETER BURNS

Jim and I have been close mates for 45 years and during that time we have shared many adventures. Since we both carry a strong streak of the larrikin, most of those moments are probably best left unrecorded. But he has always been a great intellectual companion and we have had many challenging and stimulating discussions. For Jim, architecture is not just about designing buildings. It is the catalyst that inspires thoughts about art, philosophy, the environment, politics, the rule of law and history. I can recall several times when a quiet lunch over a bottle or two of wine extended into dinner and beyond, much to the amusement of the waiters. I always feel enlightened after one of our lunches, although now it sometimes takes a day or two for the enlightenment to arrive. One of my fondest memories took place one mid-afternoon in the deserted public bar of a local hotel. Jim had just won the commission to design the library at the new James Cook University in Townsville. There was much talk, on his part involving Le Corbusier, concrete and spatial elements. He seemed somewhat obsessed with the problem of where to put the bulky airconditioning equipment and its pipes. As we chatted, he began drawing on the bar surface with his finger various possible solutions to the problems. He became more excited and began spilling beer on the bar to make new drawings. He abruptly said he had to go for a pee and left. I finished my beer and ordered another. When I had finished that one and he hadn’t returned I started to worry. A quick check of the gents showed he wasn’t there. In fact he had left the premises and gone to his office. At the foot of the stairs at my house there hangs a 50 cm x 95 cm framed drawing. It is the original first working sketch of the James Cook University Library building in charcoal. In the bottom right-hand corner there is a blue biro scrawl. It says “For F. Thompson James Birrell 2/67”. It is one of my favourite works of art.

FRANK W. THOMPSON

From 1961 to 1966 Jim Birrell was Architect to the University of Queensland and was a key player in planning the campus and designing the first buildings for the university’s fledgling campus in Townsville. The University College of Townsville was established in 1961 (becoming James Cook University in 1970) and in 1964 Jim Birrell collaborated with the distinguished university planner Professor Gordon Stephenson in preparing a “master plan for a university in North Queensland”. As University Architect he designed the first building on the new campus, a hall of residence, “University Hall” (1966). Subsequently, as the principal of James Birrell and Partners, he was commissioned for two further buildings, the library (1968) and Humanities II (1970). These bare facts give no indication of the lasting impact of Birrell’s creative and imaginative planning and design. First, the master plan combined Stephenson’s long experience in campus planning with Birrell’s skilful application of design principles such as the Burley-Griffin-style use of axis lines in the overall layout. Forty years on, the campus development shows how effective the master plan has been and how closely it has been followed. Second, each of Birrell’s buildings reflects his skill in matching architectural style with function and purpose, and in meeting the special demands of a tropical environment. The domestic feel and Spanish/Californian flavour of the red brick residential block of University Hall contrast dramatically with its concrete “facilities building”, which combines the classical Euclidean “golden mean” with Le Corbusier principles. The centrally located, highly functional library, again in concrete, is a fascinating combination of slopes, curves, circular ports and a wide, overhanging, high fascia roof. Humanities II, of inexpensive masonry block construction – with rounded ends, high-pitched copper roof and precast concrete “eyebrows” over windows – has an almost medieval, monastic feel, befitting the disciplines housed within it. As CEO of the institution during the time of Jim Birrell’s university work in Townsville, I represented the “client” and was closely involved in the genesis and development of each of his projects. I experienced first-hand the passion and the pain and the ultimate excitement of the architect at work. I well remember how the first ideas for the library were sketched in the sand at my weekender on Magnetic Island. They were heady days!

PROFESSOR KEN BACK AO

James Birrell still presents himself as an architect and planner, and it’s his bridging of these professions and his colossal grasp of the public/private interface over time and space that makes him so influential. When he came back from his 1961 Sisalkraft Scholarship, he announced that Queensland’s architects were not worthy of its developers. He might harbour similar thoughts with respect to South East Queensland’s present planners. Beyond the “professional”, Birrell’s immersion in what Peter Goldston (former GM of South Bank Corporation) called “the crypto-political” girds his work. I was reminded of this before the 2000 local government election, sitting quietly with Jim in the back of a classroom of the Toowong State School at a public meeting to “save” Toowong Library, while two contemporary political leaders rubbished it as architecture, completely oblivious of the library’s significance or Birrell’s presence. Birrell’s incredible success in convincing the political leaders of the fifties to bequeath Brisbane such a rich and successful set of diverse public facilities probably had more than a little to do with the attitude of the political leaders of the noughties. In the seventies, Jim got $8,000 for preparing a town planning scheme for the whole of Maroochy Shire (Nambour, Maroochydore, Mooloolaba). At the time we were getting $30,000 for documenting unremarkable twelve-storey beachfront apartment blocks at Mooloolaba. The redressing of this gross imbalance in priorities is one of Birrell’s most important influences. In the eighties, I remember Jim expounding the principles of a density zoning system of planning control which he had meticulously researched in the US. This approach could be infinitely better than the current infatuation with either “performance-based criteria” or “New Urbanism”. I can still see Jim on ABC TV put-putting up the river in a “tinnie”, giving us heaps for our Post-Expo South Bank Masterplan. And I can imagine him having plenty to offer on the current South East Queensland Regional Strategy. I haven’t always agreed with Jim’s critiques, but he has always pulled us forward to better outcomes and a new day. I might have direct contact with Jim only once every two to three years, but he always ennobles the moment. For example, he and his wife Franki once took me and my family on a full-day exploration of the Sunshine Coast hinterland, including a spontaneously provisioned and served barbecue lunch, while Jim extolled his long-term vision for this “Riviera” region (my family still fondly remembers that day). For me, James Birrell will remain an architect and planner.Would that the inspiration of his work and life might descend today on politicians, developers, architects and planners alike.

NELSON ROSS

James Birrell is an exceptional man. During his working life he has successfully performed the duties of architect; City Architect (Brisbane City Council); Head of School of Architecture and Town Planning (University of Queensland); principal of James Birrell and Partners, Architects and Town Planners of Brisbane and Maroochydore; specialist adviser to the World Bank on foreign aid for projects in developing countries; novelist; and councillor of the Maroochy Shire Council for a term. In concert with another town planner in North Queensland, Jim pioneered the introduction of “whole area” local government land use and town planning schemes for the state. From 1970 to mid-1980 some fifty such schemes were proclaimed, to the mutual benefit of the Government and the people of Queensland. During his term as a specialist adviser he became concussed at the “cavalier” attitude of governments, consultants and contractors towards the use of aid provided. He wrote and published a novel which clearly portrayed the attitude in the hope that some improvement would be achieved. The effectiveness of the novel is not known but it was a good read. Jim is an innovator, a sound thinker and an excellent communicator. He loves the long lunch, a good read and a healthy discussion about matters of significance (all at the one time). Those who participate in this enjoy themselves immensely and learn things of interest and value. Jim is a high achiever who really does care about his fellows – exceptional.

ARTHUR MUHL

Jim Birrell is almost quintessentially Australian – a blokey fellow, sometimes gruff, a bit of a larrikin, incredibly bright, always fair and a great mate. He is a magic example of an architect who believes in architecture and his profession and its importance to our country. Jim was a member of the National Capital Authority from November 1997 to June 2001. I would sometimes wonder, as I looked at him across the board table, whether the profession appreciated that it had such a champion of architecture in Canberra. I would enjoy watching Jim with his brow furrowed, his intense blue gaze and his almost intimidating attention to the design work before us. If the work had merit, his support was plucky, articulate and passionate. He would squarely remind all detractors that the work was for the capital of our nation, that it had to demonstrate what we had achieved and could achieve, that it had to be good architecture and that it had to serve the future, not only the whimsy of the present. When the work was less than good Jim would seek to guide the design. If it was unsalvageable he did not hesitate to say so. As chairman of the Parliamentary Zone Review Advisory Panel, he was more challenger than adjudicator. In many ways Jim set the pace for such professional panels, making it clear that their role was to advise and guide and that this demanded intellectual rigour and debate. At our Authority meetings he would present the views of his panel faithfully and with great vigour and colour. Sometimes frustrating, but always invigorating, he made his colleagues’ views and concerns spring to life and gave the report substance. He was a tough and plucky “client” for all of our projects in the capital. It was not unusual to find Jim with his sleeves rolled up at the drawing board, exploring designs with our architects to get the work built or make it better. He gave us confidence in what we were doing. Lest you think him a serious fellow, let me tell you that Jim knows how to enjoy life and helps you to enjoy it too. I have discovered that talk of architecture, people and places can run on to the wee small hours and many empty bottles of wine. Jim Birrell has been part of the Canberra phenomenon for a good part of his life in practice and scholarship. When you visit Commonwealth Place, Reconciliation Place or Anzac Parade, you should know that Jim Birrell was a member of the Authority when these projects were created and built. If you read the Griffin Legacy you will see Jim is part of that too. He has had an important hand in the architecture and planning of our national capital and in my view Australia is better for it.