Review

Jury citation

Mooloomba House. Photograph Patrick Bingham-Hall.

The RAIA Gold Medal for 2002 has been awarded to Brit Andresen in recognition of her outstanding achievements as an academic and design architect over a sustained period in Australia and overseas. Brit is recognised for her holistic commitment to an architectural vision through teaching and practice, as well her acknowledged expertise in areas such as the work of Alvar Aalto. As an educator, she continues to inspire a generation of students and graduates, particularly from the University of Queensland, to think deeply about their work. She has an international profile through lectures and teaching at various institutions, and has designed and built, in collaboration with her late husband Peter O’Gorman and other architects, some exquisite architectural projects of high quality and rich response.

With her family, Brit visited Australia, from Norway, for extended periods between 1951 and 1962. These Australian visits, particularly the experiences of eucalypt landscapes around Sydney, had a lasting effect on her childhood and her imagination.

Brit has been involved in the design of projects principally with Peter O’Gorman, and also with former students Michael Keniger and Timothy Hill. Brit has encouraged other architects to collaborate in a climate where individualism often prevails. Although the completed works folio is not overly large, each completed project has been a reference point for others and is an important contribution to architecture in this country. Brit will continue to be recognised as a design leader and educator.

The 2002 Gold Medal honours Brit Andresen’s commitment to architecture, through teaching as well as personal design excellence, as distinguished service to the profession. This has brought an uplifting and investigative approach to design which has stimulated the minds of architecture students, many of whom have become established design leaders in their own right, and illustrates the great contribution an individual can bring to the discipline and the profession of architecture.

RAIA Gold Medal Jury, Chair Graham Jahn FRAIA

Tribute by Lisa Findlay

The Burrell Museum, near Glasgow. The design competition was won by Brit Andresen and Gasson and Meunier Architects. Temporarily shelved during the 1976 downturn, it was completed as designed in the 1980s.

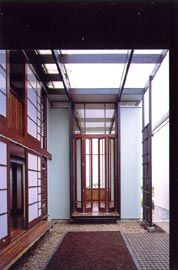

Andresen O’Gorman’s recently completed multi-purpose facility for Government House, Queensland. The pavilion juxtaposes the informal, asymmetrical awning with the formal, symmetrical dining room. The dining pavilion opens to views of the forest and lawns of the recreation area, while the base houses shower rooms, stores and machinery to service adjacent pool and tennis court. The project was completed in association with Michael Kennedy Architects. Photograph Patrick Bingham-Hall.

Brit Andresen’s childhood in her native Norway was punctuated by long sea voyages to Australia where her father was working as an engineer on large hydro-electric projects.

Little could anyone imagine that the young girl disembarking at Sydney Harbour in 1951 for the first time would one day be an internationally known Australian architect, scholar and teacher. Nor could they conceive that she would also be the recipient, fifty-one years later, of the highest honour granted by the RAIA, the Gold Medal.

Brit Andresen’s lifelong engagement with architectural teaching, scholarship and practice began during her university education. She completed her Bachelor of Architecture in 1969 at the University of Trondheim. The following year she pursued a housing research project in Eindhoven as the recipient of the Dutch-Norwegian Research Prize. In 1971 she moved to Cambridge where she established an independent practice and taught part time at both Cambridge and the Architectural Association. Students from those early years remember her teaching vividly, and her practice of that period is most notably marked by the acclaimed Burrell Museum in Glasgow, a project she won by competition in collaboration with Gasson Meunier Architects.

During these years, Andresen began to create a work life that defied the usual roles of either architect or academic. Her refined sensibility and desire to make architecture was balanced by a keen mind that craved debate and the exploration of ideas. So she entered a hybrid life of teaching, scholarship and practice - undaunted by a profession that was only just beginning to open the doors to women. While this combined approach means that work on all fronts may be a bit slower in developing, all three areas of pursuit inform each other and can lead, in maturity, to the kind of rich contributions to the field of architecture that the RAIA is celebrating in bestowing this award.

In 1977 Andresen moved to Australia to take up what she thought would be a temporary full-time position on the faculty of architecture at the University of Queensland.

There she met a quiet-spoken and charming colleague, Peter O’Gorman, whose dedication to, and passion about, both teaching and architecture matched her own. They married in 1980 and Andresen’s "temporary" stay in Brisbane has lasted 25 years.

It is quite simply impossible to write about Brit Andresen’s career without including her partnership with Peter O’Gorman. Andresen and O’Gorman were teaching colleagues, practice partners and equal parents of their two daughters. While they were a tightly knit team, each was also dedicated to, and supported in, their separate interests.

They always enthusiastically celebrated each other’s individual successes. In one of the sad ironies of life, Peter O’Gorman died in October of last year, just as the Gold Medal selection committee was meeting.

At the University of Queensland, Andresen, along with O’Gorman, was part of a small group of dedicated faculty that built the school into an exciting and lively place to study. Over the years she has become one of the finest architectural educators in Australia, winning a Teaching Excellence Award in 1990 from the University of Queensland and teaching graduate students in architecture one term per year for three consecutive years at the University of California at Los Angeles.

Andresen’s teaching demands intellectual rigour while maintaining respect and room for the ideas and concerns of the student - a difficult and necessary balance when teaching architecture in studio. She is intolerant of any kind of laziness and always pushes her students beyond first answers and simple solutions, insisting they develop their own sense of integrity and purpose about architecture. Her own generosity and intellectual curiosity inspires colleagues and students alike. The studios she teaches often encompass the concerns of her practice by exploring the making of an architecture fine-tuned to its landscape.

Few people in architectural circles know the depth of Brit Andresen’s scholarship.

She has presented papers at international conferences and has published several book chapters, and numerous journal articles and building reviews. Her scholarly work falls into two general categories: applied analysis and criticism, and architectural history. The analysis work includes Andresen’s internationally known work on the landscape and site strategies used by Alvar Aalto, and research and publications on shading - a critical architectural topic for sub-tropical Queensland - with co-authors L. Listopad, R.

Kennedy, and M. Keniger, and several pieces of architectural criticism.

Twenty years ago Andresen became concerned about Australia’s rapidly disappearing architectural heritage, particularly in Queensland. This led to two projects - one with Michael Keniger and a number of students entitled "Main Street: Queensland Country Towns" which worked with 90 small towns. Her other project, "Anglican Churches in the Diocese of Brisbane", evolved into a series of research projects that have, a bit unexpectedly, spanned twenty two years. These have yielded papers and publications, conservation and preservation reports on specific churches, consultation work with the Diocese regarding planning and construction, and significant contributions to the dialogue about heritage buildings in Australia. The largest part of this work is the ongoing compilation of an analysis and history register of pre-1903 parish churches which has grown to such proportions as to become Andresen’s PhD dissertation topic.

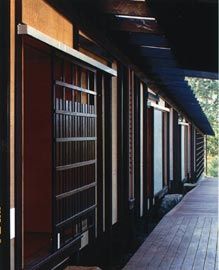

All of this teaching and research has had important influences on Andresen’s work as a practicing architect. Over the years Andresen O’Gorman Architects developed a refined architecture that celebrates dwelling in Queensland. Their work, primarily residential, is a meeting ground for the poetic and the pragmatic. The projects gently heighten the sense of being in a particular landscape and in a climate where one can merge outside and inside a great deal of the year. The site is always acutely observed, with topography and vegetation enlisted as architectural elements. These are integrated with the building to form a continuous set of paths and places in which to live the moments of life. The buildings have carefully orchestrated material palettes, which are often experimental and always finely crafted. In places, these materials are deployed in layers that can be adjusted to account for the demands of weather, privacy, and shade.

The sets of fine battens that have come to be identified with Andresen O’Gorman are built reminders of all of these concerns: they break apart the mass of the building, cast cooling filtered shadows like the leaves of a eucalyptus, and celebrate the power of the accumulation of small moves. The allure of this elegant strategy is evident in the number of times it has been borrowed by other architects.

As is evident in the internationally published Rosebery and Mooloomba houses, restricted budgets and modest briefs seem to challenge these architects to their best work. Widely published and exhibited in Australia, their work has also been published in Japan, Korea, the UK, France, Italy and Germany and exhibited in Italy, France, Spain, Malaysia, Singapore and the Phillipines. In 1999 they were included in the Record Houses issue of the US Architectural Record and the practice is one of 100 top international firms identified in the recent publication 10 X 10. They are also included in three recent books on architecture in Australia. They have lectured widely in Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Canada and the US about their work. A monograph on their practice, with essays by Andresen and O’Gorman, is due from Visionary Press this year.

This condensed version of the scope and depth of the work life of Brit Andresen would leave anyone a bit breathless. What marks all of it, without exception, is intelligence and rigour, thoroughness and care, and an abiding dedication to the importance of the role architecture plays in an ever more complicated world.

Lisa Findley is associate professor at the California College of Arts and Crafts in San Francisco. She is an architectural journalist, a contributing editor to Architectural Record, and author of the forthcoming book Constructing Culture: Architecture,

Ocean View Farmhouse, Mt Mee, 1994

The slopes of the Ocean View Farm spread from the end of a great spur, with high views of both the Samford Valley to the south and the coastal plain to the north-east. The owners required a timber farmhouse for occasional use, incorporating images and qualities associated with Australian gable-roofed sheds.

Intention. The design explores ideas about the experience of enclosure and interaction with the landscape. Formal underlining, concealment, framing, and implying the miniature are explored to extend visual coherence and to heighten the awareness of the landscape.

Site selection. The site was selected for its northern orientation, its shelter from the prevailing south-east wind, its open terrain, views and landform. Sited across the ridge of the shallow spur, the house benefits from the fall to the west for roof water collection, a defined foreground to the north, and views to landscape elements at varying focal lengths. These views include the horizon, the ocean and the astonishing volcanic cones of the four Glasshouse Mountains on the coastal plain. Large stones form the threshold as "little sisters" to these remote topographical monuments. Views of distant landmarks and related closer elements are accentuated or related by the design of the farmhouse. These elements combine reciprocally, to visually and experientially link the house to the landscape.

Landscape. The project raised the question of how to establish coherence and interaction between a small building and an open landscape.

The design describes the landform, establishes a landscape scale, introduces transparency, and orders lines of movement linked to topography and views. A single cut along a contour retained by a low masonry wall limits interference with the ground. Set 600 mm from this wall, a parallel wing of rooms stretches 30 metres across the spur to reveal and underline the slope and scale of the landform. The first view of the house from the hill above aligns the ridgeline of the roof with the horizon line, intensifying the interaction between the landscape and the architecture. The gable apex on the south elevation aligns with the fold of the spur, both marking the entry to the house and describing the hill slopes with its eaves, while also recalling the traditional farm shed. On the other side, the hill slope changes and the roofline of the north elevation is made as a single eave falling with the land to the west. The north and south walls introduce peripheral transparency, scale play, and a trellis "landscape". The horizontal timber battens of the south wall overlay profiled metal sheets, changing the scale of the wall and introducing shadow animation. These battens continue past the metal cladding to form transparent enclosures that "feather" the form with the landscape.

Climate. The house, conceived as an outstretched and protective wing, shelters the site from prevailing winds. The farmhouse rooms form a windbreak along the east-west contour and curl to the north to make a sheltered corner facing the sun and the views. The owners’ apartment acts as a "shoulder", contributing to the windbreak and forming a sunny corner at the heart of the house in a gesture of "embrace". The closed cooler southern wall contrasts with the permeable, warmer northern edge.

Garden. The integration of building and landscape required a simple landscape strategy that has not been completed. Cattle grids, steps and a "ha ha" were to define territorial limits close to the house, with the pastures creating a visual continuity between the house and the hillside. On the south wall, timber battens make a super-scale trellis designed to support vines to veil the building and to intensify its connection with the landscape. To the north, the gap between the house and the deck is a planting zone for a thick hedge. This was intended to increase the sense of privacy in each room, to amplify the threshold between inside and outside, and to include, close by, the animation and decoration that plants bring.

Plan. The farmhouse is essentially a self-contained, one bedroom apartment with a string of attached service areas. Access from the deck to the pastures is via outsized steps and an extended wooden ramp that also connects the bunkhouse and workshop.

The floor levels step across the apartment offering a close relationship with the ground, defining the territories within an open plan, deepening the northern view from the kitchen sink and giving greater ceiling height and a sense of distance from the entry to the main room. The spatial containment of the outside room is supported by extending the eave and by the fireplace. The decking is made as an island, formed as a raised element and a "thing" to be sheltered. A stone threshold between inside and outside is formed as a continuation of the hearth of the fireplace, foreshadowing the more intimate shelter inside. The outside room is planned both as a substitute garden and as the social centre of the farmhouse.

Project credits

Ocean View Farmhouse

Architect Andresen O’Gorman. Architectural Collaborator Michael Barnett. Engineer John Batterham. Contractor/carpenter TAYCON, Tom and Tim Taylor. Photographer Brit Andresen, opposite page, Simon Kenny, above, and Reiner Blunck.

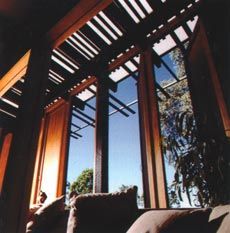

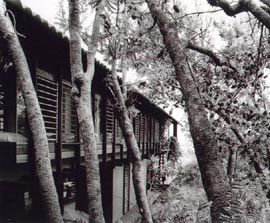

Mooloomba House, North Stradbroke Island, 1995-1999

In this house inside rooms interconnect with outside rooms, courtyards and garden to form a continuous "inhabited landscape". The largest space is the central courtyard bordered by a raised walkway that serves as a fish-cleaning table, a firewood store and access to the wooden bathtub. The raised deck, along the slope of the hill, also opens to the courtyard and connects to a two-floor gallery containing kitchen, stores, toilet, shower and bed alcoves. One end of this long north-south wing terminates against the hill, the other in a belvedere overlooking the ocean. The prefabricated gallery structure, on a regular grid, contrasts with the flanking structure, built from cypress poles and rough-sawn timber rafters set at irregular spacings.

Landscape. The house defers to and underscores the existing landscape. It also evokes a mythic landscape and creates a fantasy landscape. The existing hillside, with its grove of banksia and folding topography, predominates as the first level of habitable territory. Within this landscape the central courtyard is a "roofless room", bordered by timber decking and enclosed, in part, by a tall "built hedge" of frame structures overgrown with vines.

The incomplete site enclosure maintains a sense of the scale and continuity of the larger landform, while the boundary structures make formal alliances with neighbouring structures, particularly on the east where a common scale, structure and material aids visual continuity. Deferring to the landscape, the house is built as one edge to the central garden. A level of correspondence is found between the open-weave framework of the house, its colour, scale and transparency and the structure of the trees. Structures extend into the landscape and the landscape extends into the structures. The movement sequence from the hill to the ocean view, along the narrow upper walkway, links the earth and the sky, stretching the experience of the landscape space from near to far and from miniature to super-scale.

The evocation of a mythic landscape recalls elements of a child’s tree house and the bower in Milton’s Paradise Lost. It is not so difficult to accept the coastal sub-tropical landscape as the primitive paradise garden and the banksia grove as a clearing for its bower. The "inwoven shade" of the lookout nest connects with the adjacent trees and is designed to evoke qualities of the bower. The sleeping alcove, the studio aedicule and the lined "cave" room set in the "forest" of the rest of the house reiterate this. The creation of a parallel fantasy landscape is intended to intensify both the mythic landscape and the reality of the existing landscape. The constructed "forest" of thirteen cypress poles and irregularly spaced rafters merges with the existing trees along the western boundary. In conceptual terms, two rooms and two planted courtyards are built within this constructed "forest". The "cave" room is lined, more enclosed and has a fireplace. On the north, a vine-covered planting frame encloses the aedicule within the translucent studio-bower. Layered battens, vines and translucent corrugated acrylic sheets on the west make a wall animated by shadow play on the inside, and a vertical garden outside.

Construction and architectural intent. This project continues to explore the expressive capacity of construction through metaphor, geometry and the material properties of hardwood. Eucalyptus hardwood is usually concealed in stud framing systems because it tends to shrink, harden, warp, twist, cup and crack after milling. This seems an unfortunate loss of architectural opportunity, both in terms of the material’s high strength and durability, and its potential to contribute to a building’s expression. The Mooloomba House counteracts hardwood’s excessive lateral movement by vertically laminating thin members of opposing grain and sandwiching a 1200 mm wall panel of 18 mm waterproof ply between. The frame also functions as wide "cover battens" over the sheet joints. Exposing the frame as a skeletal structure and allowing it to play an expressive role develops three principal ideas. The first draws on Rachel Fletcher’s 1988 essay "Proportioning Systems and the Timber Frame", where she explains that an ancient Greek word for harmony (harmonica) was a carpentry and joinery term meaning "a timber frame such that to take away one piece would collapse it". The frame components must fit together harmonically to make a whole. In the Mooloomba House the generative 2000 x 1200 (1:1.618) proportion of the expressed panel and primary frame links this ancient meaning with the harmonic proportion, supporting its visual integrity.

The second idea is that space can be characterised by its constructional form. Tectonic space for example, made by the open weave assemblage of relatively thin stick elements, characterises the bower. Stereotomic space, defined by mass and continuity of surface characterises the cave. The house juxtaposes three different constructional forms (all hardwood) in three different parts of the building, held together through forms of what Aldo van Eyck called "reciprocity". The third intention, made possible by the benign climate of Stradbroke Island, is to use the tectonic structure to extend opportunities for describing space through transparency. Such opportunities are found in the bridge between technology (material and technique), light, territoriality (the plan) and the relationship to the landscape.

Project credits

Mooloomba House

Architect Andresen O’Gorman. Engineer John Batterham. Contractor Lon Murphy. Carpenters Graham Mellor and Peter O’Gorman. Assistant Peter Nelson. Photographer Patrick Bingham-Hall.

Rosebery House, Highgate Hill, 1997

Site. This beautiful but complex site is part of a north-south gully that terminates at the Brisbane River. A fragment of steep, leftover bushland, the gully’s sense of remoteness within its suburban setting is due to a fold in the topography and to large trees to the north and west that both limit and direct views beyond the site. Retaining the spatial and physical continuity between the hill and the river was important, and the long, undulating gully influenced in the decision to site a narrow timber structure along the east slope. The space of the landscape also affected the choice of materials, structure, circulation patterns and building form.

Site, plan and form. The site is dark for much of the year. In order to secure north light to the interior, particularly in winter, the pavilions are separated by open decks. The decks are screened by timber-battened walls and awnings clad in acrylic to provide additional cover, privacy and shade for the outdoor eating areas. The tilt of the skillion roof exposes a strip of glazing to the western sky, bringing winter light to the upper level rooms. The east elevation forms a low "blind" wall along the boundary to neighbouring properties to reduce visual impact and increase privacy. On the west, the pavilions and interspersed decks are bound together by a long timber battened screen.

The screen, and the interstitial spaces between screen and house, mediate between enclosure and landscape and were designed to mask or frame views of the site and of the surrounding "borrowed" scenery. The arrival sequence involves stepping through the line of the screen to climb the stairs behind, which widen with the rise towards the river.

The upper deck then projects beyond the screen, into the high branches of the camphor laurel tree to the west, acknowledging the view to the river.

Program. The children’s bedrooms are located on the upper level, close to the daily activities associated with dining, kitchen and decks. These upper bedrooms are linked, via the north stair, to the parents’ bedroom at the lower level. Each adult has a small personal space, linked across the entry deck, which can be combined for events such as exhibitions or a party. In the future, the teenagers or young adults might occupy a small, selfcontained apartment on the lower level with the parents moving upstairs. The lower entry deck, planned for family access and overlooked by eating areas above, can be screened off by three sliding gates for security or to direct access along to the main stair leading to the sitting room areas. The kitchen/dining room forms the centre of the house, with its glazed walls visually connecting the family area with the adjacent decks and the landscape.

The sitting room provides a place for retreat and includes a fireplace for winter comfort. A raised day-bed, along the south wall, opposite the fireplace, is sheltered by translucent batten screens that slide open to reveal the view to the river.

Landscape, transparency and enclosure.

The timber landscape screen reinstates the edge of the gully, both as a defined volume and at the scale of the landscape, while also masking the domestic scale of elements of the house behind. This timber framework, made from Australian eucalyptus, supports vertical battens and finer climbing frames for vine growth. It is envisaged as a super-scale planting screen to re-establish and underscore the qualities of the gully. The long "woven" screen helps blur the familiar dimensions of a two-floor house, establishing the relationship with the landscape as the major reference and providing another layer of transparency and enclosure beyond the room. The planted outer screen permits the selective erosion of the room enclosure and allows filtered light and views through the floor-to-ceiling glazing. The glazed pavilions are simultaneously open and protected.

Project credits

Rosebery House

Architect Andresen O’Gorman. Architectural Assistant Michael Barnett. Engineer John Batterham. Contractor/carpenter Lon Murphy.

Photographer Patrick Bingham-Hall.

Moreton Bay Houses, 1999-2001

The project was originally intended for a community of four single independent women who, living in adjacent apartments, could offer one another support. Four apartments were to be built over two adjoining lots, with some shared facilities and common gardens. Zoning limitations, however, permitted only one dwelling per site with tight constraints. To conform to regulations, two houses were built with private and common gardens.

Planning. The introduction of small lot subdivision for single occupancy houses in established suburbs has brought with it new planning regulations, principally intended to ensure contextual development and to safeguard amenity. The contemporary "three bedroom/two bathroom" house, regardless of household size, tends to be considerably larger than the older "workers cottage" - in terms of room area and room number. Consequently new houses on small, narrow lots often fill the entire permissible building envelope, resulting in long, two-level structures with terrace house-type planning. Light, ventilation, garden access and outlook for the central rooms are usually compromised. These factors also thwart the traditional Queenslander house form. Attempts by the local authority to identify features or elements associated with the "Queenslander" are well intentioned, but they do not reach to the core generators of the house form nor its interrelated construction methods.

Working within these parameters, we sought to strengthen the visual reading of the two narrow houses as one, and to establish something of the scale and proportions of houses on larger lots. The other proposition was to make the principal structure as a large planting frame, encouraging a vertical garden. This is intended to contribute to the streetscape through its most coherent element, the planting, and to propose a new sub-tropical model for the suburbs.

Site plan. To maintain the idea of shared territory a binding arrangement was made where external common areas could be established across the sites. The common zone links the entry court, the central palm court and the north garden. The long site enabled a set of courtyards in a sequence from streetside to bayside. This land/water axis establishes the common street entry, through the timber screen, into the central court and to the lower garden following views of the bay. The street court enlarges the combined frontage and makes a generous entry. The central court is conceived as the largest room in the house, providing a common area and a sheltered retreat in summer.

House planning. While each house functions as conventional single occupancy house, with guest facilities, they have been designed to retain the future possibility of housing a singles’ community.

The original program required that the two principal apartments be on one level and easily accessible from the car court. The ground level apartments are accessed along the north-south axis and the future upper level apartments along the east-west axis, midway along the side boundary. The living area is made as a "Great Room" to amplify the presence of the bay and to relieve the sense of tight containment on the narrow site. Tall windows and doors in the great room allow rooms further back on the site to benefit from the north light and views to the bay.

Construction, material and form. Composite vertical supports, made of twinned hardwood posts on either side of a plywood panel, and 300 mm deep timber beams create a structural frame that establishes a major scale and prominent order throughout the project. Secondary and tertiary scales are made by elements such as the timber trelliswork, screens and climbing frames. The primary structure acts as a giant-order trellis, creating habitable places below for indoor and outdoor rooms.

Architecture. The subtropics invite imaginings of living in a garden paradise and sheltering amongst "inwoven shade". The architectural strategy in this project has been to make a vertical garden from large garden trellis structures that can be variously occupied. This proposition allows the exploration of ideas related to transparency, metaphor and landscape alliances. Super-scaled planting frames and screens extend well beyond the weather enclosure to suppress the visual reading of the wall plane and promote the skeletal structure. The planting frames are exposed on the interior and exterior to sustain their role as independent structure. Horizontal strip glazing under the beams further amplifies this legibility.

Project credits

Moreton Bay Houses

Architect Andresen O’Gorman. Engineer John Batterham. Contractor/carpenter Greg Thornton Constructions and Graham Mellor. Photographer Patrick Bingham-Hall.