Celebrating Richard Johnson – his oeuvre and his contribution – with tributes by James Weirick, Stephen Frith and Gerard Reinmuth.

JURY CITATION

Richard Johnson is a most worthy recipient of the Gold Medal, the highest honour the RAIA can bestow. The award recognizes Richard’s exceptional body of executed work and his outstanding contribution to the development of the profession in Australia.

Richard Johnson was educated in Sydney at the University of New South Wales, graduating in 1969 with First Class Honours and the RAIA Silver Medal. He continued his education at University College, London, receiving a Master of Philosophy in 1977. He has served the community in various capacities including, most recently, as a member of the board of Australian Technology Park and the Redfern-Waterloo Authority. He has lectured and taught widely and has been an Adjunct Professor at the University of New South Wales since 1999.

At an unusually early age Richard was awarded an MBE, in 1977, for his work as architect on Okinawa Expo 75 in Japan. In 1985, in collaboration with Yoshinobu Ashihara, he completed Expo 85, Tsukuba, in the same country.

More recent examples of his work include: 363 George Street (1999), Art Gallery of NSW Asian Gallery (2003), Hilton Hotel redevelopment (2005), Westpac Place (2006), Arts of Islam exhibition at the Art Gallery of NSW (2007), new work at the Sydney Opera House in association with Jørn Utzon, and the National Portrait Gallery – due for completion in December 2008.

Richard comments that his early work in Japan, along with his education at UNSW, particularly under Professor Peter Kollar, was influential in developing his architectural direction. Today his work reflects an exquisite understanding of space, use of materials and sensitivity to the contribution of architecture in the public domain.

Richard’s design process combines masterful leadership with a willingness to collaborate with other distinguished architects, including those within his practice. He has fostered an inclusive approach to the design of many buildings and places of significant technological, spatial and urban complexity. Richard’s work also demonstrates the value of a multi-disciplinary approach to architecture. It integrates, as appropriate, urban design, landscape architecture, interior architecture and exhibition design to form a cohesive and distinguished body of work that now spans four decades.

Richard’s architecture is characterized by clarity in expression, form and execution. The sensory experience is generated by exceptional spatial concepts, which often solve complex functional requirements with apparent simplicity. The work typically involves new significant public spaces at the ground plane, improving existing urban conditions. As a result, his architecture is widely respected for its contribution to the visual experience and amenity of the public domain.

His work also typically defines public places through distinctive and appropriate architectural forms developed with meticulous attention to detail. Each building reflects the essential properties of the materials used and techniques of construction. The architecture, in effect, embodies a sophisticated appreciation of context, material technology, environmental engineering, structure and conditions of practice. As a result we experience through his work an authentic representation of our culture in time and place. This ensures continuing relevance and appreciation of Richard’s contribution to the built environment in the future.

The work has a sense of certainty and permanence – confident without being intrusive, rigorous in conception and executed with exemplary skill. His buildings stimulate a feeling of wellbeing and dignity for users and visitors alike.Perhaps the most enduring legacy is also the most elusive to appreciate. Experiencing Richard’s architecture encourages contemplation of the work of others, as we are automatically engaged with a study of the interconnecting elements of urban fabric. The work connects people and their actions in history. It reflects our communal responsibility to design better places through collective actions. This work expresses a commitment to provide public environments that are designed and built to exceptional standards.

Richard’s work represents architectural and social constructs of significance. This is architecture that is selfless – architecture that is memorable, functional and exceptional.

The work of Richard Johnson is awarded the 2008 Gold Medal. Through this we recognize the enduring contribution of meaningful architecture to enhancing our lives, and those of all who follow.

2008 RAIA Gold Medal Jury: RAIA National President Alec Tzannes, RAIA Immediate Past President Carey Lyon, 2001 Gold Medallist Keith Cottier, Professor Philip Goad, Melinda Dodson.

1969–1985

PRINCIPAL ARCHITECT, COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT

Collaboration

Yoshinobu Ashihara, Jim Maccormick, Jack Torzillo, Stan Dolton, Paris Drake-Brockman

Paul Berkemeier, Mike Boyd, Bruce Bowden, Jim Caddaye, Peter Collins, Neil Durbach, Tony Fabro, Stephen Frith, Paul Gallagher, John Lambert-Smith, Peter Page, Phil Page, Mike Rolf, Greg Scott-Young, Andrew Wilson.

Photography

Max Dupain: FFG Workshop, National Biological Standards Laboratory.

1970

HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT COMPETITION, LONDON

Richard Johnson, Peter Page

Fourth place in a two-stage international competition for a new parliamentary building in London, to house office and conference facilities for Members of Parliament, with links to the House of Commons.

1979

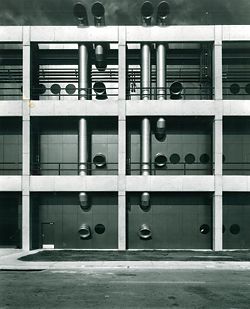

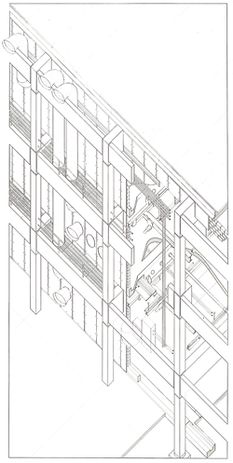

FFG WORKSHOP

Richard Johnson, Paul Berkemeier

A highly serviced workshop building for FFG guided missile frigates on Garden Island. The building integrates structure, building services and FFG equipment maintenance and testing services and relates to a maritime aesthetic.

Merit Award, RAIA NSW Awards, 1980.

1980

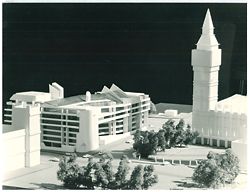

NATIONAL BIOLOGICAL STANDARDS LABORATORY

Richard Johnson, Peter Collins, Jim Caddaye, Mike Boyd

A research and testing laboratory complex at Symonston, ACT, was designed to accommodate the scientific, administrative and support activities of the National Biological Standards Laboratory (NBSL) and the Australian Dental Standards Laboratory (ADSL). The integrated development was designed for future flexibility, high levels of servicing and microbiological security. The project was fully designed and documented but not built.

1985

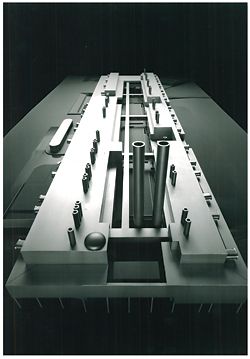

AUSTRALIAN PAVILION EXPO 85, TSUKUBA

Richard Johnson, Paul Berkemeier

The Australian Pavilion at Expo 85, on the theme of Science and Technology, presented Australian advances in science and technology in a sequence of integrated exhibition galleries incorporating exhibits and audiovisual techniques.

1985–2000

DIRECTOR, DENTON CORKER MARSHALL

Collaboration

Jørn Utzon, Gae Aulenti, Bill Corker, John Denton, Barrie Marshall, Adrian Pilton, Jeff Walker, Sunny Yeung

John Andreas, Brad Baker, Lucy Bannyan, Paul Berkemeier, Neil Burley, Sue Carr, James Casserley, Belinda Chan, John Crosley, Geoff Crowe, Richard Desgrande, Renate deTorre, Garry Emery, Peter Emmett, Diana Fisher, Susan Freeman, Paul Geehan, Iain Halliday, Christopher Hansen, Catherine Hart, Leo Hoefsmit, George Korban, John Lambert-Smith, David Langston-Jones, Clive Lucas, David Melocco, Bob Nation, Graham Parry, Steve Pearce, Brooke Pinker, Gerard Reinmuth, Paul Rolfe, Terry Tam, Matthew Todd, Alec Tzannes, Peter Watts, Barry Webb.

Photography

Max Dupain: Australian Embassy, Beijing.

John Gollings: All other projects this section.

1988

SPANISH PAVILION EXPO 88 BRISBANE

Richard Johnson

The Spanish Pavilion at Expo 88 Brisbane, won in competition, displayed Spanish art and plans for the future Expo in Seville. The design evoked a feeling of Spain through the use of Andalusian colours, water, grilles and classical planning.

1990

AUSTRALIAN EMBASSY BEIJING

Richard Johnson, Tony Fabro, John Denton, Barrie Marshall, Bill Corker, Bob Nation, Adrian Pilton

An embassy compound comprising the Ambassador’s House, Chancery, Staff Apartments and Recreation Centre of the Australian Mission in Beijing. The design responds to traditional Chinese urban planning.

International Award, RAIA National Awards, 1992.

1992

LOYOLA COLLEGE

Richard Johnson, Steve Pearce, Kiong Lee

A Jesuit school in the western suburbs of Sydney. Built on a heavily wooded site, the design is organized around cloistered courtyards and a central axis on which the library and chapel, the “mind and spirit” of the school, are placed. The masterplan and design provide a strong sense of place and quality for buildings of a modest budget.

Merit Award, RAIA NSW Awards, 1993.

1993

SPENCER RESIDENCE

Richard Johnson, John Lambert-Smith

A three-level single residence on a sloping waterfront property fronting Middle Harbour in Sydney. The house is for a family of two adults and two independent children. The design is based on a 12-metre cube embedded in the side of the hill, which slopes down to the waterfront. From the higher, street-level entry the house appears quite unobtrusive, allowing neighbourhood views over the rooftop garden to the harbour beyond.

1993

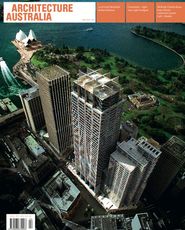

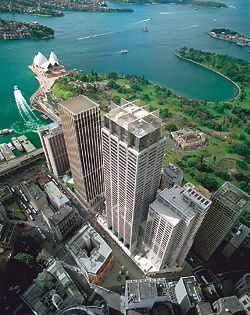

GOVERNOR PHILLIP AND MACQUARIE TOWERS

Richard Johnson, Jeff Walker, Adrian Pilton, Barrie Marshall, Bill Corker, John Denton

This 64-level commercial office tower is part of the First Government House site – a project won through an international competition. Located in the core of the financial and legal precinct of Sydney’s CBD, Governor Phillip Tower was completed in 1993 and Governor Macquarie in 1994. It is distinguished by its optimum floor plan and is oriented to maximize the views across the Botanic Gardens and Sydney Harbour. All floors receive excellent natural light and are column-free with a clean central core.

Sulman Medal, RAIA NSW Awards, 1994.

Commercial Award, RAIA National Awards, 1994.

1994

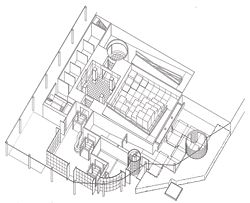

MUSEUM OF SYDNEY

Richard Johnson, Steve Pearce, Paul Geehan, Adrian Pilton

The Museum of Sydney, built on the remains of First Government House, creates a series of urban rooms and gallery spaces to interpret the site, our colonial past and the current city.

Lloyd Rees Award for Urban Design, RAIA NSW Awards, 1995.

Merit Award, RAIA NSW Awards, 1997.

1996

PYRMONT BAY PARK

Richard Johnson, Adrian Pilton, Paul Geehan, Matthew Todd

The final stage of Pyrmont Bay Park, at the eastern end of Pyrmont Bay, responds to the maritime and industrial character of the area.

Merit Award, RAIA NSW Awards, 1997.

Walter Burley Griffin Award for Urban Design, RAIA National Awards, 1997.

1999

363 GEORGE STREET

Richard Johnson, Jeff Walker, Kiong Lee, Peter Blome

A 35-storey, 40,000-square-metre commercial office building elevated above existing historic buildings. Selective demolition has created generous civic spaces, with the foyer contained within a glass-enclosed loggia. The raised tower allows for the penetration of daylight and the visual appreciation of the heritage buildings. A public through-site link re-creates the notion of laneway and access, long lost in Sydney.

Architecture Award, RAIA NSW Awards, 2000.

Commercial Award, RAIA National Awards, 2000.

2000–2008

DIRECTOR, JOHNSON PILTON WALKER

Collaboration

Jørn Utzon, Adrian Pilton, Jeff Walker, Kiong Lee, Graeme Dix, Paul van Ratingen

Peter Blome, Andrew Christie, Wayne Dickerson, Matt Morel, David Springford, Adrian Yap, Carol Zhang

Scott Balmforth, Richard Blythe, Jim Caddaye, Angelo Candalepas, Belinda Chan, Peter Collins, Anne Flanagan, Susan Freeman, Clive Lucas, Ken Maher, Sophie Pickett-Heapes, Gerard Reinmuth, Richard Rowell, Richard Tam, Jamie Wanless

Photography

Jennie Carter: Dead Sea Scrolls, Arts of Islam.

Eric Sierins: AGNSW Asian Gallery, Sydney Opera House, Australian Museum.

Richard Glover: Hilton Hotel, JPW Studio.

Brett Boardman: Abbotsleigh, Westpac Place.

2000

AGNSW DEAD SEA SCROLLS EXHIBITION

Richard Johnson, Adrian Yap

The exhibition, designed in collaboration with the Art Gallery of New South Wales, presented a selection of Dead Sea Scroll fragments along with related archaeological material from the nearby Khirbet Qumran site.

2002

ULTIMO AQUATIC CENTRE COMPETITION

Richard Johnson, Kiong Lee

This competition entry (unsuccessful) attempted to house the facilities of the Aquatic Centre – pools, change rooms, gym, et cetera – in a podium that related to the sandstone escarpments of Ultimo. The roof of PTFE inflated fabric, controlled by cylindrical geometry, acts like a cloud sheltering and shading the pool.

2003

AGNSW ASIAN GALLERY

Richard Johnson, Graeme Dix

The new Asian Gallery allows the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ permanent collection of Asian Arts to expand, and provides space for travelling exhibitions. The extension’s double-skinned vented glass facade filters daylight, allowing works to be displayed without totally isolating the gallery from the outside environment. At night, this facade glows from within, the simple, geometric language referring to traditional Asian lanterns and giving the gallery presence and scale within the Sydney skyline.

Architecture Award, RAIA NSW Awards, 2004.

Commendation for Public Buildings, RAIA National Awards, 2004.

2004

JPW STUDIO

Richard Johnson, Kiong Lee, Richard Rowell

Johnson Pilton Walker’s office is a clear realization of the design ethos and culture of the practice: a collaborative studio environment where projects are developed to make lasting contributions to our built environment. The design of the new office is focused on a multipurpose central space, which is used for a variety of events and activities: staff talks and presentations, formal and informal meetings, and entertaining.

Corporate Interior Design winner and Best of State (NSW) winner, Interior Design Awards, 2006.

Australian Timber Design Award, 2006.

2005

HILTON HOTEL SYDNEY REDEVELOPMENT

Richard Johnson, Paul van Ratingen, Peter Blome

This major reconstruction project reinstates the Hilton’s prominence within the Sydney skyline. The grand sun-filled public spaces and links to the Town Hall and the Queen Victoria Building contribute to civic life in the core of the city. The hotel contains amenities and conference centre facilities that set a new standard for the region. The existing guestrooms and commercial office facilities are updated to current market expectations.

Architecture Award and Civic Design Award, RAIA NSW Awards, 2006.

Commercial Award, RAIA National Awards, 2006.

2006

ABBOTSLEIGH RESEARCH CENTRE

Richard Johnson, Graeme Dix, Richard Tam

The building provides a range of teaching, social and research spaces across three levels, and creates a new civic meeting space linking the eastern and western sections of the campus. The design sets out the resource collection in a series of timber and metal structures that define the primary structural and architectural grid.

Public/Institutional Commendation, Interior Design Awards, 2007.

Australian Timber Design Award, 2007.

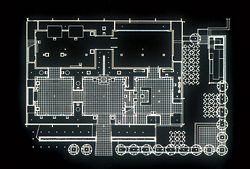

2006

WESTPAC PLACE

Richard Johnson, Jeff Walker, Kiong Lee, Graeme Dix, Adrian Pilton

Located on the western edge of Sydney’s CBD, this development (originally called the KENS project) covers a one-hectare city block. JPW were selected through a limited design competition conducted under the Sydney City Council Design Excellence guidelines. The design response to the large, complex and historic site demonstrates the potential for a development to make a significant contribution to the public realm as well as satisfying commercial objectives. The project has created the largest new public landscape park in the CBD for more than a century.

Lloyd Rees Award and Architecture Award, RAIA NSW Awards, 2007.

2007

AGNSW ARTS OF ISLAM EXHIBITION

Richard Johnson, Jamie Wanless

The design for a major exhibition of Islamic art from the Professor Nasser D. Khalili collection. The exhibition design arranged 350 works in a sequence of rooms inspired by concepts of Islamic art and architecture and showcased the diversity in artistic traditions of the Islamic world. The central room of the exhibition re-created an Islamic dome in light.

2008

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY

Richard Johnson, Graeme Dix, Adrian Pilton, Adrian Yap

Won in open international competition, the National Portrait Gallery will be the most significant new national institution constructed in the Parliamentary Triangle for almost 20 years. The design draws inspiration from Canberra’s climate and unique natural light, the essential character of many Australian rural structures, the institution’s art collection and its purpose: to increase the understanding of the Australian people – their identity, history, creativity and culture – through portraiture. The building embraces its setting, and links the visitor’s experience of the gallery spaces to the Australian landscape, with views into the landscape from transition spaces and controlled natural light illuminating the galleries.

2008

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM

Richard Johnson, Graeme Dix, Matt Morel

When complete in 2008, the eight-storey Collections and Research Building will house some of the Australian Museum’s 80 research scientists and 14.5 million specimens. The building is the first phase of Johnson Pilton Walker’s strategic masterplan, and the first significant building project undertaken at the Australian Museum for more than 20 years. The external design of the new building responds to the heights, massing, materials and detailing of the surroundings. The contemporary building extends the main museum complex in a way that is clearly of its time, but also respectful of the past and the significant heritage of the existing complex of buildings.

1999–2008

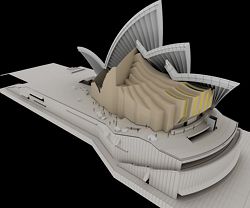

SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE

Utzon Architects in collaboration with Johnson Pilton Walker.

Utzon Architects: Jørn Utzon, Jan Utzon;

JPW: Richard Johnson, Kiong Lee, Matt Morel, Wayne Dickerson, Belinda Chan, Sophie Pickett-Heapes.

2004 Utzon Room

Utzon Architects in collaboration with Johnson Pilton Walker refurbished a reception room as part of the ongoing venue improvement programme at the Sydney Opera House.

2006 Western Foyer

The Western Foyer services three performance spaces: the Playhouse, Drama Theatre and the Studio. Utzon Architects in collaboration with Johnson Pilton Walker is currently working on the interiors, providing these spaces with access and views to the Western Boardwalk and harbour. For the first time since the building opened in 1973, patrons experience entering the western theatres while always being oriented in the spectacular harbour setting of the Sydney Opera House.

2007 Opera Theatre Study

Utzon Architects in collaboration with Johnson Pilton Walker completed a design study for a new opera theatre within the existing Opera Theatre Shells, with improved acoustics, sight lines, capacity and back of house.

The public role of the architect

Richard Johnson in conversation with Stephen Frith.

In early January Richard Johnson and Stephen Frith spoke about Johnson’s career and commitments. This is an edited transcript.

The public role of the architect occurs where the architect mediates the public realm and private interest. I have been lucky enough to work at a scale where there is never just one author in an undertaking, nor should such authorship be claimed – certainly I can’t claim it. I feel humbled by this honour of the Gold Medal, and want to recognize those with whom I have enjoyed many creative working relationships, with people like Yoshinobu Ashihara in my early years, with colleagues at Denton Corker Marshall, with Jørn Utzon, and more recently at Johnson Pilton Walker, in particular with Jeff Walker and Adrian Pilton.

The role of the architect is to sell the vision of the public realm to others, to have an idea, to clearly express it, and to keep reminding clients to ensure that this vision is not being eroded. We check for opportunities where the public realm and private commercial interests coincide. Good public space has levels of enjoyment that have commercial value. Harry Seidler did it in Australia Square, and we try to do it – to push the boundaries, to show the client where to buy an adjacent site, close a road, incorporate public life into a project for the greater good. This is true for Westpac Place, the Hilton project, and 363 George Street.

These projects originated in competitions. Even if you don’t win, you learn a lot by looking at what others have done, which encourages a serious evaluation of what you have done yourself. There is no point in thinking that all your ideas are better. You win a competition with an exquisitely clear, legible response to the aspiration and functional requirements: it leaps off the page.

We often win competitions because of the urban focus of our projects. In Westpac Place Sydney now has a new urban park! The lawn at the heart of the project attracts northern sun, and there are always young children in it – parents meet each other there for lunch with their kids. This project was all done within strict commercial parameters. Once the vision was sold, it was protected, and a lot of people have ownership of it. It is clearly expressed and appropriate for the context – this is what architects do. We can elevate a client’s aspirations, as we did at the Hilton Hotel. We convinced the client that it should be a five-star rather than four-star urban civic hotel connected to the Town Hall precinct. We interconnected public spaces, with the elevation of the Queen Victoria Building as a backdrop, whose sandstone columns are echoed in the playfulness of the pillars at the entrance. While it’s a private commercial hotel, we have created a great public room – the foyer is now back on the ground level and connected to the street.

The engagement of the public with our work is also enhanced through our designing of exhibitions. In Australia, exhibition design is not part of the mainstream of architecture as it is in Europe, and it adds another dimension to our practice. We do about one exhibition a year for the Art Gallery of New South Wales; we have just completed the Islam exhibition. This work developed from our design of the Asian Galleries wing. Like our Expo architecture, it is not just about the interior, but about the movement of people, the experience of space, the physical and symbolic context, about practice at a broad level. It is significant that all of our projects involve artists. They interpret site, context and space in different yet complementary ways from architects.

Building a house

The Spencer House at Cremorne in Sydney is the second house for the same client, on a harbourside site. It is beautifully finished and built, and is an intimate house. The money was spent crafting it and making the materials work, and making the spaces liveable and connected with place, rather than making a strong expression on the street. You look at the roof and the roof garden and drive down to the court, from which you enter the house and look through to the water. The client had spent considerable time in Japan, and collected art there, and was sympathetic to what we were trying to do with materials. They were sensitive in regard to the Japanese concept of space. There was a nice connection between what the client wanted and what I would have wanted for myself.

I have been more influenced by traditional architecture than by contemporary work. Traditional Japanese architecture has been especially influential, for there is always more beneath the surface. I now go to Katsura Imperial Palace as often as I can – I have been there five or six times – in as many different seasons as possible. I am immeasurably humbled by it – such skill used by its architects, controlling the vistas and space, the heightening of the senses through shadow, smell, colour, form and space, and processional experiences. Katsura was designed for the moon viewing. The guests were escorted on a journey to a platform from which to experience the moon at a certain time of the year. The most incredible thing is that, though highly constructed, the landscape and architectural arrangement feel accidental and constantly changing. With the garden the control seems effortless, full of complex layers that affect all the senses. I often think that if it is possible to control these things at Katsura, it is possible to solve any particular architecture problem you are facing.

Architecture and experience

I have learnt much from others about Japan. Yoshinobu Ashihara, with whom I worked on Expo 75, Okinawa, and Expo 85, Tsukuba, explained many things to me. He was a humanist and an internationalist. I am attracted to architects whose work takes a simple idea that can regulate the building and its elements in a particular context. A building can then have a certain authenticity, that wherever you look in whatever dimension, the parts work together, like the landscape in the valley in which I live, from hundreds of different species evolving together with an inevitable sense of relationship to place. I desire an architecture that is both inclusive and singular – Louis Kahn at the British Museum of Art at New Haven, or in the Kimble Museum, where there is an authenticity of materials working together. Jørn Utzon talks about this quality often. The materials of a building become the finish; there’s a sublime simplicity about these works. This was the thing that captured me especially about Alvar Aalto – everything contributes to the expression of the whole. He once said that when you design a window, you design it as if someone you love is standing in it. His is an architecture of humanism, oriented to how people feel in the space rather than simply a concern for what it will look like. Utzon also works in this humanist tradition, oriented to human experience.

There is in Japan a unique focus on the joint, the junction between materials, where a mediation occurs, a third element introduced to make manifest its particular material qualities. An example in our own work is leaving the welded seams on large steel columns unground – they have their own quality, which becomes the decoration of the column. Each has its own difference, like the trees in the valley where I live, which are a testimony to the uniqueness of how a tree exists in a particular place. Each is subtly different, its shape and colour different, but each exists in relation to a family of elements, with an organic inevitability in their relation to each other. My wife Maureen belongs to a group that weeds foreign plants from the valley, and propagates seeds from the existing species of great diversity, bringing harmony back to that place. It is important to use materials that are logical to their own nature; if you break that logic, then the building won’t work. People will intuitively feel uneasy in it. I have become more and more interested in natural light, and in the art of its substitution by artificial lighting. I like what Louis Kahn says, that at the instigation of a building the light is not yet there. Through the building of the work the light reveals itself. Certain materials manifest their character in different ways. If you don’t polish a stone you can see the stone in ways that you can’t if you polish it – its veins, its structure, its colour, its texture – all different if you polish it. Materials determine how a building is put together; the tectonic character of a building is about how it becomes legible.

I am against architecture as a brand. Architecture needs to be seen in all seasons, it is an experiential art. It is like the difference between a still image and a moving image. A lot of architects are preoccupied with the still image, the iconic moment, the emblematic shot. It is not that that is not sometimes meaningful, but if that is all there is, then the piece of work remains unexperienced. In an architecture of continuity, you don’t know it but you are enveloped slowly and subtly – a bit like Katsura – it seeps into you, and reveals itself slowly, this profoundly moving, symbolic power of architecture. This is really important – architecture’s emotional power.

Order through proportion

Setting up a complex proportional system, where one creates rhythms and systems of relations, is important for architecture just as it is for music. I am frustrated by what I don’t know, and am frustrated by architects who make no effort to connect with contemporary culture. This is very important to me. If we are to experience and interpret our time, we have to know the best performers and thinkers of our time, and to be informed by them. An example is minimalism – you see it in architecture, hear it in music, see it in drama and in art – all these mediums give you an understanding of it. The best minimalism in architecture is profoundly intricate and simple, like the music of Arvo Pärt or Philip Glass. In infinitely simple themes even a surprise can spring from something fundamentally predictable. The language of poetry, of music, is about timing and spacing. These notions of harmony have snuck into a lot of our projects – sometimes intuitively. The National Portrait Gallery incorporates the most rigorous application of an ordering system that I have used so far. Yet at the centre of the work is the perception of architecture through the senses.

My father taught me to have two goals in life, one that can, with effort, be achieved in one year and another that is a lifetime goal. If the latter even comes within reach, it must be elevated to a higher level of architecture through the senses.

Stephen Frith is Professor of Architecture at the University of Canberra. This is an edited transcript drawn from a conversation with Richard Johnson in January 2008.

Urban Architect: the work of Richard Johnson

Year 5 project from 1968, by Richard Johnson, Peter Reynolds, Lorienne Humphrey, Ian Sansom and Barry Sneyd, for a studio run by George Molnar at UNSW. The scheme involved reactivating Sydney’s Queen Victoria Building.

363 George Street, Sydney – “an essential place of city life”. Denton Corker Marshall, 1999. Photograph John Gollings.

The luminous pavilion of the Asian Gallery at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. Johnson Pilton Walker, 2003. Photograph Eric Sierins.

Westpac Place, Sydney, raises the tower above the ground plane to generate new public spaces. Johnson Pilton Walker, 2006. Photograph Brett Boardman.

Queen Victoria Building forecourt proposal, final-year project from the UNSW Molnar Studio.

Looking to the Queen Victoria Building from the interior of the first-floor bar at the Hilton Hotel Sydney. Johnson Pilton Walker, 2005. Photograph Richard Glover.

Principled, powerful and compelling work – James Weirick raises a glass to an architect of the city.

The architecture of Richard Johnson presents a clear and compelling case for the continuing vitality of rationalism in the making of the modern city. The inner logic of his work, revealed with precision and grace, is predicated on the idea of order embedded in the contingent conditions of the city – an order made manifest through pure geometries and pure forms expressed in new combinations of structure, space and materials. Produced over the past forty years in association with key collaborators, up to and including his current partners, Adrian Pilton and Jeff Walker (founding principals of Sydney-based Johnson Pilton Walker), this body of work stands as a powerful antidote to the anti-urban mainstream of Australian architecture. The inspiration and impetus for Richard Johnson’s work resides in the city itself.

This position was strongly established at the outset. In student work from the University of New South Wales in the 1960s, which gained Johnson the RAIA Silver Medal (awarded in those years to the “outstanding student of Architecture among all students of Architecture in Australia”), the urban condition was the generator of design ideas in a portfolio of projects produced in the Year 5 George Molnar Studio. This studio contemplated the commercial core of Bondi and the little-valued Queen Victoria Building (QVB) on George Street. The latter scheme, undertaken with Peter Reynolds, Lorienne Humphrey, Ian Sansom and Barry Sneyd, is still a striking testament to deep thinking about the city. In the face of preferred options of partial and total demolition, the team retained and reactivated the QVB in its entirety, not as a curiosity in twentieth-century Sydney but as a civic statement integrated with the Town Hall and St Andrew’s Cathedral through the creation of a city square on George Street – an idea still seriously discussed in Sydney today. In 1968 this was astonishing. The key to the scheme was not the heroic traffic solution or the new Town Hall Station, but the recognition that the sandstone buildings of nineteenth-century Sydney were the soul of the city, whose qualities could be reasserted through the geometric clarity of civic space.

The continuation of a search for civic order found expression in the Stage 1 and Stage 2 entries in the Commonwealth-wide competition for the Houses of Parliament, Westminster, prepared with Peter Page in 1970/1971. The Sydney team was selected as a second-stage finalist from a field of 245 and was ultimately placed fourth. The jury, chaired by Denys Lasdun, had included Robin Boyd for Stage 1. The project involved an office annexe and conference centre for Members of Parliament, sited between the tower of Big Ben and New Scotland Yard. The Johnson/Page solution looked beyond the picturesque imagery of A. W. N. Pugin and John Nash to find generative order in Charles Barry’s classical plan of the Palace of Westminster and the “architectural promenade” implied in the movement of parliamentarians to the House of Commons across the urban space of Canon Row. (The competition was won by Robin Spence and Robin Webster, but the project did not proceed.) The tragic death of Boyd in 1971 on his return from the Stage 1 judging in London marks the end of Australian modernism as an unproblematic movement committed to a better future. Modernism turned from diagrammatic solutions and a celebration of sun angles to more modulated fusions of technology and culture. This tendency was anticipated in the Australian Expo pavilions at Montreal and Osaka designed by Boyd in association with James Maccormick at the Commonwealth Department of Works. With the loss of Boyd, the creation of Australia’s Expo environments moved in-house as a total design challenge in the Department of Works. By this time, Richard Johnson had joined the Sydney office of the Department as a graduate architect after a cadetship served during his student years. In a short time, he was able to create a distinctive design atelier in the amorphous organization, otherwise known for all-concrete telephone exchanges. He first worked on the Australian Pavilion at Expo 74 Spokane with Maccormick; then with his own team he designed the Australian Pavilions at Expo 75 Okinawa and Expo 85 Tsukuba Science City. The latter transformed a building shell designed by Kiyonori Kikutake into a celebration of Australian science and technology. Designed at the height of the Hawke Government’s enthusiasm for a high-tech future, the sequential experience of the Tsukuba pavilion came together as a recalibration of the Corbusian concept of an acoustic space filled with light and sound to evoke vastness, ingenuity and unlocked mysteries.

An unbuilt project from this period took a similar approach to human space, abstraction and the sublime. The 1980 scheme for the National Biological Standards Laboratory at Symonston in the Jerrabomberra Valley, Canberra, responded to a programme that required secure, strictly quarantined research laboratories and, at the same time, a stimulating environment for cross-disciplinary scientific enquiry. The conflicting demands of interaction and isolation were resolved in an “academical village,” Jeffersonian in its human-scaled spaces, stretched across the landscape in a machine-like world of precision and exactitude.

The Australian Embassies in Beijing and Tokyo were the most significant projects initiated during Johnson’s tenure as Principal Architect in the Commonwealth Department of Housing and Construction (as Works had become by the mid-1970s). Both embassy projects involved complex negotiations at all levels in Australia, China and Japan to realize the formidable expectations that surrounded the mission of modern Australia to the great capitals of Asia.

Work began on the Beijing Embassy in 1977 and, in due course, the Beijing authorities assigned a site in the still-rural Chaoyang District, east of the Forbidden City, adjoining the Canadian Embassy. During the masterplanning phase, overseen by Johnson, Denton Corker Marshall was appointed design architects in accordance with the long-established practice of awarding embassy commissions to major Australian design practices. At this stage of the project, the fundamental parti of the embassy as a walled courtyard complex was determined – a mark of profound respect for the traditions of Beijing urbanism – together with the challenge of opening and inflecting the wall to express the presence of an open society in the midst of post-Mao China.

The Beijing project was long delayed in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution, and not brought to completion until 1990. In the meantime, Denton Corker Marshall had been appointed as design architects for the new Australian Embassy in Tokyo. This was a project necessitated by a razor-gang decision during the first Hawke Government to sell Australia’s remarkable landholding in Minato-ku, south-west of the Imperial Palace – 1.5 hectares valued at $2.1 billion at the height of the Tokyo land boom. This grand estate, complete with a 400-year-old garden and a lavish 1920s mansion, had been acquired from the family of Marquis Masaaki Hachisuka following the occupation of Japan in 1952. With the site earmarked for sale in the early 1980s, Johnson directed masterplanning studies on behalf of the Commonwealth. A measure of wise counsel prevailed in Canberra. Less than a third of the land was sold – 6,000 square metres for $607 million. The 1920s mansion was lost, but the Tokugawa garden was retained, and the new embassy complex – given an urban presence on the street frontage to the north – was integrated with the traditional landscape on the south in a way that salvaged something of Australia’s cultural reputation.

During the Tokyo project, Johnson left the Commonwealth and joined Denton Corker Marshall as a director. He established the Sydney office of the firm and by the late 1980s was involved in the competition for commercial development on the site of First Government House. This competition went through several complex stages before the commission was awarded to Denton Corker Marshall. Undertaken as a collaborative venture between the founding principals in Melbourne and the new Sydney office, the initial Leonidov-like sketches of the office towers captured the constructivist ambitions of the project, raised as an heroic structure above surviving fragments of colonial Sydney. In design development, these fragments came together as a thoroughly urban ensemble – a gift to the city on every front in terms of massing, materials and proportions. Nowhere was this more convincing than at First Government House Place and the Museum of Sydney. This “urban room” on Bridge Street was created by the key decision of the Denton Corker Marshall competition scheme to set back the commercial tower from the Bridge Street building line. This served not only to protect the rediscovered footings of First Government House, but also to ennoble the space with the presence of the sandstone buildings of James Barnet and Walter Liberty Vernon on either side. The new sandstone plinth, colonnade and walls of the Museum of Sydney, executed with skill and brio unseen in Sydney for generations, demonstrated that the genius of the past could come alive in an urban drama of today.

For the first time since the 1920s, the streets of central Sydney became the generators of an urban architecture in which the programme and scale of the commercial tower met the ground in heroic yet harmonious spaces of everyday experience. The interaction of geometry, structure, materials and light transcended the “podium and tower” prescriptions of the Sydney planning scheme to give integrity to each element. In the office tower at 363 George Street and the extraordinary transformation of the Hilton Hotel, the spatial qualities of frames, voids and shafts unlocked programme and activities in a way that went beyond signature moves to make these essential places of city life.

In 2001, at the time of the Hilton commission, the Sydney office of Denton Corker Marshall was re-formed as the independent practice Johnson Pilton Walker. From this period, the work was stripped of stylistic conceit. The major development on the KENS site – the city block on the western fringe of the CBD bounded by Kent, Erskine, Napoleon and Sussex Streets – was won in competition, as was the Hilton project. It demonstrated the power of the “architecture of the city” as a generator of commercial solutions and compelling form. This design, now known as Westpac Place, replaced the developer’s tentative solution of twin towers on a podium with a large-floorplate double slab, strategically raised above the site to interweave existing urban texture and new north-facing public spaces. These turn to advantage the unlikely combination of building undercroft and freeway undercroft.

The major cultural projects of recent years – the Asian Gallery at the Art Gallery of New South Wales; additions to the Australian Museum, Sydney; the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra – inject rational order into complex and conflicted settings to reveal the underlying strength of the original architecture. The luminous, lantern-like pavilion of the Asian Gallery reasserted the presence of the AGNSW on the eastern side of the city after the appalling depredations of the Eastern Distributor engineering works. Across town at the Australian Museum, the Johnson Pilton Walker masterplan and new research wing on William Street will bring together the remnants of incomplete building campaigns that have dogged the institution since Barnet’s initial work of the 1860s. In the Parliamentary Triangle, Canberra, the National Portrait Gallery will have its own presence on Prince Edward Terrace and reinforce the exhilarating space of the high-level podium of the Colin Madigan/EMTB High Court and National Gallery.

In this series of commissions, the quest to reveal the inner integrity of the original work is motivated by deep respect for the original architect. The same approach has given Johnson’s most significant professional challenge true strength and substance. For the past ten years he has worked with Jørn Utzon to recover the design principles of the Sydney Opera House and redress, at least in part, the unforgivable events of the 1960s that drove Utzon from the project. The outcomes from this new conversation and collaboration with Utzon range from the convincing to the contentious, but there is no question that they have been advanced with deep sincerity, through a process that has set the standard for all time on how one architect honours the work of another.

The architecture of Richard Johnson is principled, powerful and compelling. On a late afternoon in Sydney, take time to sit against the curve of sandstone that forms one of the great elliptical columns in the first-floor bar of the Hilton. Look across George Street and feel the empathy with the facade of the Queen Victoria Building. Remember the QVB project from the Molnar Studio forty years ago – and all that has been achieved since – and raise a glass to a great architect of the city.

James Weirick is Professor of Landscape Architecture and Director of the Graduate Program in Urban Development and Design at the University of New South Wales.

a true professional

New work on the Sydney Opera House with Jørn Utzon – “the greatest example of Richard’s sense of commitment and service to the profession”. Photograph Eric Sierins.

Gerard Reinmuth reflects on lessons learnt from his mentor Richard Johnson about the nature of the profession, and how to be a committed professional.

It is a great honour to be invited to contribute to this celebration of Richard Johnson’s career, and to help illuminate the importance of this quiet achiever.

I met Richard when applying for a job in 1995, as a student recently arrived in Sydney after extended travels overseas. The one building that had really impressed me on my return was the Museum of Sydney – a sophisticated and urbane project in what is still something of a frontier town. The architects’ handling of the site, the deep integration of artwork and the dense layers of meaning embedded within the arrangement and fabric of the building all suggested that the project was a marker in the architectural history of the city. Of particular interest was the fact that the power of the object was derived from its relational qualities in context and its instrumentality in revealing the potency of the site, a place of critical importance in the history of the nation. I wanted to work with the author.

I remember arriving for an interview and being disappointed that I was not faced with an intense character in a black T-shirt – such are the prejudices of an architecture student. Richard presented himself as a quiet man in a well-cut suit (perhaps a deliberate foil to his prodigious yet highly controlled intellect), but I left with no doubt as to his passion for architecture. That passion continues to infect me and those fortunate to work alongside him today.

This sensibility – intense yet highly restrained – provides a lens through which Richard’s work and his contribution to the profession might be understood. His private nature – driven by shyness and the constant self-critique typical of the best people in creative fields – means that celebrity does not suit him at all well. He rarely participates in the performative end of the profession, rarely gives lectures and will almost never express strong opinions among people he does not know well. Unlike many of his generation, Richard has no school of followers and would never see it as appropriate to inflict the cult of hero-worship on impressionable students. He operates in a genuinely humble way, the least narcissistic architect I know, working to the best of his ability on every aspect of an architect’s craft and on every project. His ambition is high, but the ambition is for an exceptional outcome as opposed to increased personal notoriety, and so in striving to meet this ambition his only competitor is himself. Perhaps the price for such genuine humility has been a lesser influence to date than might otherwise have been. This makes the award of the 2008 Gold Medal an important moment for our profession – it brings an opportunity to widen his audience, as uncomfortable as he may be in the spotlight that will shine as a result.

My 1995 job interview started a relationship with Richard that has taken three distinct forms over the past decade. He is firstly a mentor, secondly a supporter of our fledgling practice, and now thirdly a collaborator with Terroir on occasional competitions and projects. While each of these engagements with Richard has been of direct personal relevance to me, I believe the lessons learnt have critical importance for the profession as a whole.

Richard’s most distinctive lesson is his understanding of what it means to be a member of a profession and to conduct oneself in a professional manner. In terms of professionalism, I have not seen another architect in this country equal Richard’s extraordinarily thorough and complete mode of operation, nor his tightly constructed and strongly enforced ethical code. In addition, few of us practise in such a way that the idea of architecture as a profession is a central belief driving our actions. By adapting to the paradigm of the service provider, we have lost our way as a profession. This means that Richard’s approach is critical and the awarding of this year’s Gold Medal is hugely important.

Language and concepts are inextricably linked. Thus, as the nomenclature of our profession expands to include ideas of project management, customer relations, service provision, market focus and so on, we lose the basis on which the profession was founded. Richard gives excellent client service (many of his current clients are of more than ten years’ standing), manages projects tightly and with great effectiveness (outdoing any project manager) and always works from an understanding of the fiscal and market pressures of a project. However, he addresses these issues from within a framework based on an overarching sense of his responsibility to the society that trained him and to the profession he serves as a result of that training. In exercising this responsibility Richard comes into being as an architect and he faces each new project with this sense of duty.

As someone who has been educated by Richard during the formative years of my professional life, I have not only been fortunate to receive a complete exposure to his sense of duty, but have witnessed constant affirmation of this in practice, day after day, project after project. His rigour and consistency should be the benchmark to which we all aspire, but there are so few like Richard that opportunities for mentorship are scarce. I despair that so many will not experience such an architect at close hand in their career.

The few who by luck or design have sat across from Richard at a drawing table are fortunate indeed. Given the scale of his practice, it has astounded me that Richard found so much time for those eager to learn, often staying late to complete a conversation that may have started early in the afternoon but which needed to continue into the night to explore the issues fully. These precious conversations will be remembered by all who have worked with him closely; they locate architecture as a crucial cultural act and, as such, encompass connections to the full range of cultural and political activities, from art to music, politics and history.

I learnt much from Richard as an assistant safely tucked under his wing, but it was not until he expanded his tutorial role into a regular and generous counsel of my entire practice that I saw the power of his approach – a power that becomes apparent when your life, or at least your practice as you have envisaged it, literally depends on it. Richard has spent countless hours since the inception of Terroir guiding us through issues as diverse as fee agreements, practice structure and ownership, intellectual property and moral rights, ethics, design, politics (inside and outside the practice) and so on. Richard’s generosity to us and to others stems from a sense of service to the profession and a desire to see that profession survive as a new wave of architects start to navigate their place within it.

The greatest example of Richard’s commitment and sense of service to his profession is ongoing – his assistance to Jørn Utzon on the masterplanning and gradual refurbishment of the Opera House over the past eight years. This often thankless task has been subject to much critique and speculation, and it is extraordinary that so much of the commentary on the collaboration has overlooked the astounding political and ethical impact of actually making peace with Utzon. The profession will eventually understand that Richard has performed a profoundly selfless job in shepherding and shielding Utzon from the worst of architectural practice in the new world, thus enabling Utzon’s continued involvement on the more civilized terms he may expect, given the conditions of practice in Scandinavia. For Richard to have given much of the last decade to the service of another architect at perhaps the most critical point in his own career is extraordinarily generous. The enormity of this is little understood, but perhaps it can only be understood by another architect.

I hope that the awarding of this Gold Medal sheds light on this commitment and on other aspects of Richard’s extensive career, and perhaps sparks renewed interest in the idea of the profession of architecture in this country, and thus its survival. For the critical role of the architect in society and as the senior authority on projects has diminished over the past few decades. How did this occur? A simple answer in this context is that we have lost ground because more of us do not practise in the spirit that Richard practises and do not love being an architect as he loves being an architect.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge the jury and their wisdom in selecting Richard Johnson as the recipient of the 2008 Gold Medal. In this decade alone we have seen a couple of Melbourne larrikins, an international operator and an immigrant trailblazer acknowledged. This suggests that, unlike other awards, the hindsight possible when awarding a Gold Medal is of great value. With the choice for 2008 we further expand our understanding of what a good architect can be, and through this the profession to which Richard has committed himself so completely has hope for continued relevance in the future.

Gerard Reinmuth is a director of Terroir.