Raymond Jones Architectural Projects, curated by Simon Anderson and Andrew Murray for the Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts at the University of Western Australia, is the seventh in a series celebrating the work of Western Australian architects. Although eight years have passed since the previous retrospective, the university and the event’s sponsors are to be congratulated for reawakening their program and helping to invigorate Perth’s architectural scene.

Exhibitions are part of the staple diet of design cultures. They are occasions for reflection, as the curatorial act calls the present into question and by extension must also suggest a future. The past need not be seen as a nostalgic glaze over dead or inert objects. Considered actively, history operates as an agent to “disturb the present as we know it,” calling our time into question and judging us and our architecture for what we are not – for what architecture has forgotten or overlooked or has yet to achieve. Operative history draws attention to continuity as an essential part of creative progress. So, in addition to enjoying the social buzz of a well-attended opening, students and young practitioners get to see primary source material that is a tradition of the discipline and to contemplate the curators’ plotting of larger socio-cultural patterns.

This exhibition is dense with drawings of Jones’s wide variety of essentially modest works over a long and productive career. The practice’s finely drafted plans, sections, elevations and details are a delight. These now fragile documents show a career-long interest in the practical benefits of clear graphic communication, embedded knowledge and pride in the craft and aesthetic quality of architectural drafting. The contract drawings show a stripped, empirical language and clarity of purpose in Jones’s pursuit of a constructional logic honed for unadorned, low-cost buildings. His early research into delivering functional, modern architecture through modest means continues to underscore the mannered experimentation of his later designs. A romantic spirit, essentially latent during his early career, can be seen later in colourful perspective renderings, such as the 1962 illustration of South Fremantle footballers in dramatized action, with a proposed grandstand for the great team’s home ground as their backdrop, and in his recent non-figurative paintings offered for sale, with the proceeds going to help homeless youth, a cause with which Jones is closely involved.

Floreat’s Church of St Cecilia by Raymond Jones.

Image: Robert Frith

Having studied under Robin Boyd, Jones migrated from Melbourne in 1953 after a few years of practice. He soon found his place in Perth’s changing architectural scene and became an important contributor to the defining shift in the local paradigm. His early works in Western Australia stay close to the strain of domestic modernism developed locally by several architectural practices. The house designs were characterized by utilitarian functionality and by respect for the effect of climate on comfort, on the effectiveness and durability of building materials, and on the architectural form. The expanded decade of the 1950s was an exciting and explorative period, one of two high points of Western Australian architecture. Despite deep ties to British values and social politics, the allure of American suburban life was beckoning. On offer was a different way to live, a new reality that appealed to a young society. To embrace this new vision, local architects and planners sought new forms of accommodation and expression and Perth and its suburbs changed irrevocably. Civic projects such as Council House were commissioned, followed by Beatty Park Leisure Centre and Perry Lakes Stadium for the 1962 British Empire and Commonwealth Games. A freeway, a bridge across the Swan River and a network of new roads enabled speedy access to modern houses on bigger lots constructed over virgin scrub. These and later projects such as the Mount Lawley and John Forrest high schools took modern architecture into existing suburbs and set the tone for the next manifestation of the city’s growth rings. The new architecture was a blend of European heroic modernism, with its underlying socialist interests, and Californian mass-market suburbanism, with its promise of comfort and individual freedom. This new vision symbolized a unified, healthy, egalitarian community ready to enjoy the emerging affluence and optimism of the postwar economy.

Ainslie Road House.

Image: Raymond Jones

In place of the rustic charms, the solid, load-bearing brick walls and the heavy, pitched, tiled roofs of Mediterranean bungalows and English cottages, Jones offered minimal, stripped-back, horizontal spaces arranged under low-pitched or flat roofs made with long sheets of prefabricated metal or fibrous board. Plan arrangements were less cellular, more casual than their predecessors. Appliances and technologies such as solar water heaters, concrete floor pads and swimming pools were introduced by Jones. Windows aligned with thin planar walls shaded by wide eaves framed partially enclosed courts and views into native gardens, signifying changing attitudes to privacy, territory, family hierarchy and climate, and an appreciation of outdoor living, all of which are now commonplace. These were the characteristics of the new domestic form pioneered by Jones and a generation of Perth architects, who developed a modest and restrained take on Los Angeles’ cool and sophisticated Case Study Houses.

Over the course of his career, Jones’s projects moved away from a local modernism that favoured utilitarian and collective values towards an eclecticism more conducive to individual desires. By the mid 1960s the tenets of international modernism and its functionalist vein were under attack and its ideological underpinnings, compositional strategy and mode of expression were being critiqued by renewed interest in architecture’s communicative capacity. Later, Robert Venturi famously cited examples of basic, utilitarian forms – which he termed “dumb boxes” – that easily accommodated a varied program of functions, activities and identities, with the complex ensemble masked by a distinctive feature – in other words, a big sign. Semiotics supplied the theoretical tools needed for new explorations into the reframing of architecture as signifying text. The contrived manipulation of elements and space, a core preoccupation of modernist architects, and the formal expression of use and program were put aside in favour of architecture’s capacity to communicate across space, to enter into dialogue with a wider set of cultural practices.

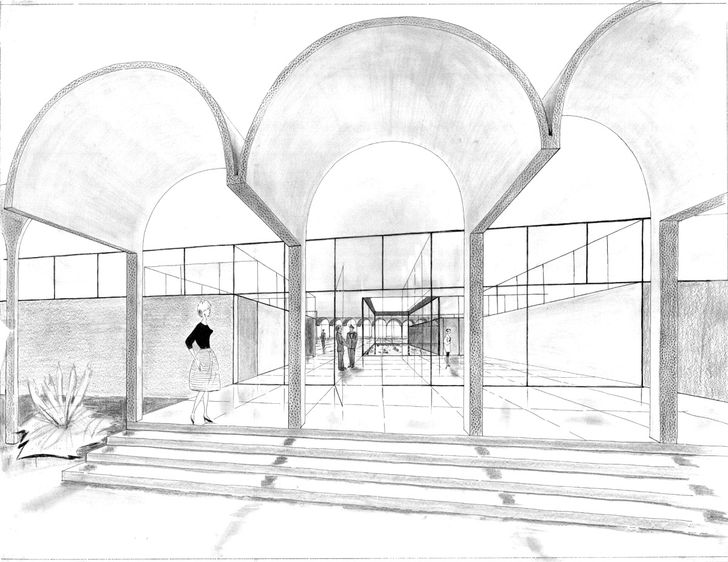

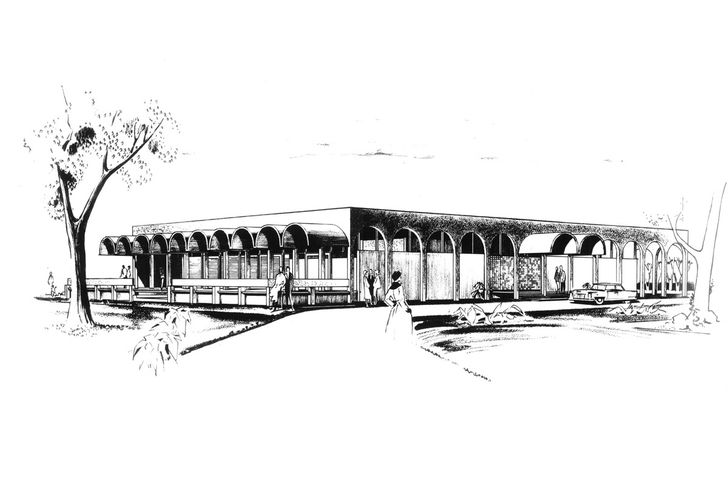

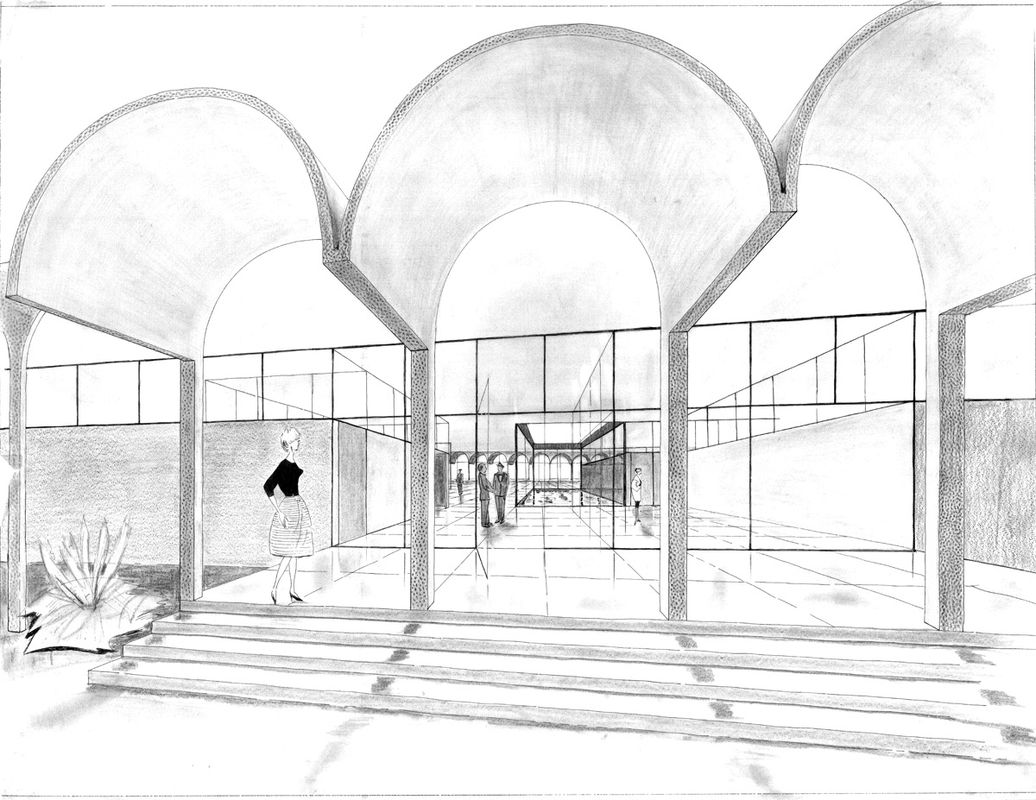

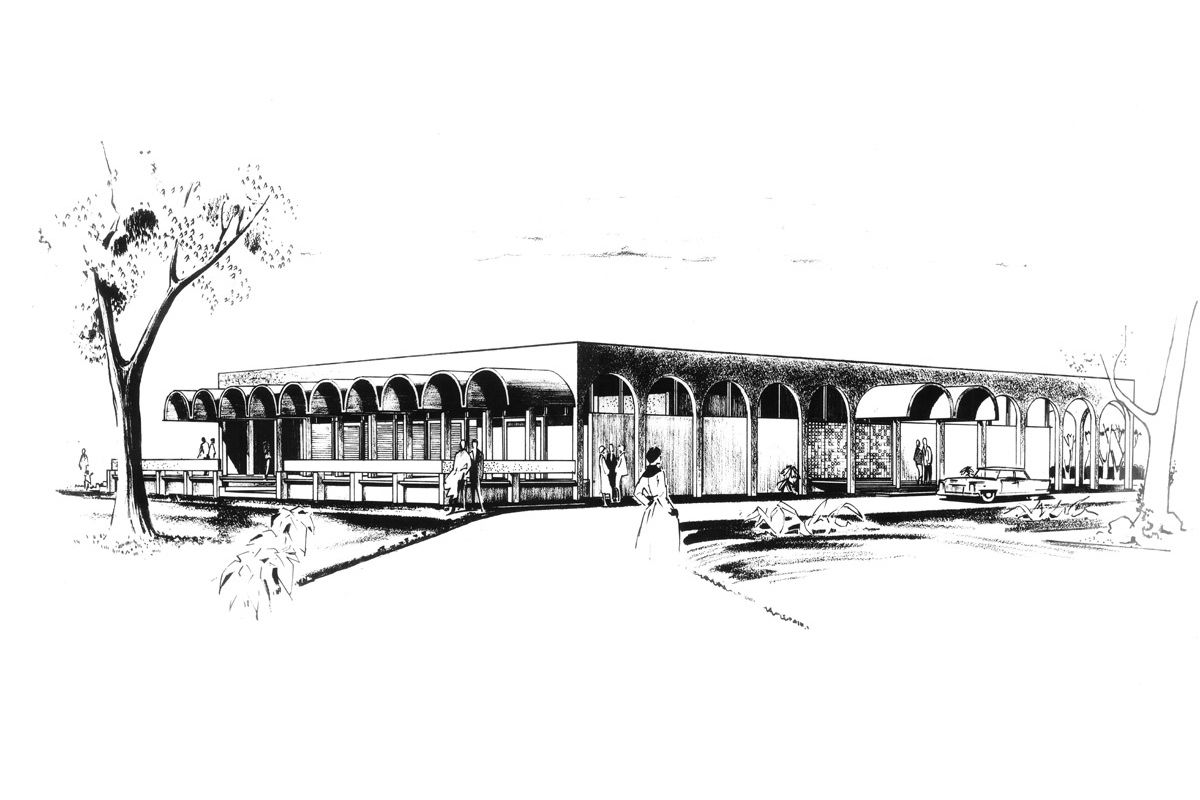

The entrance to the unrealized University of Western Australia Staff Club.

Jones’s drift from late modern functionalism can be seen when comparing his 1953 designs for houses in Victoria to the mannered expression of his unrealized design for the University of Western Australia’s Staff Club. The section drawing of this eclectic design shows Jones’s commitment to an economical and practical construction technology, still a defining characteristic of Western Australia’s architects and builders. The project’s siting and floor plan are bone-dry, matter-of-fact functionalism reminiscent of Alison and Peter Smithson’s 1954 school at Hunstanton. Yet the cool perspectives feature sharply defined planes that regulate the interior into horizontally proportioned rectilinear shafts of space, tightly bound together into a neutral and independent box form. Jones was then compelled to mask the stoic form, the result of late modernism’s formal aesthetic and functionalism’s disinterest in a theory of beauty, with a bright and lively arched colonnade. The staccato rhythm achieved by this rationalist motif is interrupted with barrel-vaulted canopies projected beyond the flush perimeter plane to signify entry and alfresco terrace, and to legitimize the colonnade by the integration of symbolic and practical function. While marking a respectful tie to the revivalist style of Winthrop Hall and the Chancellery – treasured icons of the university that continue to play a seminal role in shaping Perth’s urban identity – Jones’s proposal for the Staff Club brought together aspects of international modernism, rationalism and functionalism. This design is an early example of Jones’s emerging interest in realism and its broader base for architecture.

Raymond Jones’s unrealized design for the University of Western Australia Staff Club.

As the new decade of the 1960s unfolded, Jones’s designs began to ease out of functionalism’s straitjacket and to try on the fragmentation and eclecticism typical of architecture’s shift from forms to signs. Jones experimented with new designs for several Catholic churches. The plans take on the concentric nature of hexagonal or pentagonal geometries, enabling the architect to create a singular volume in place of the traditional cross form. The facades are a boldly playful composition of sculpted columns and geometric wall panels, interlinked with glazing units that emit strong shafts of light and create contrasting shadows. In these new churches, Jones explored a different approach to congregation and instruction, which warranted a decidedly adventurous aesthetic and a very different spatial quality from their more traditional predecessors. It is worth noting that while functionalist architecture derives the massing and form of a building from the literal shaping of its programmatic requirements, its prioritizing of use reveals functionalism’s humanist foundation, a sentiment that has remained with Jones throughout his career. His search for a local language continued in the domestic work of the 1970s to 1990s, which shows the influence of Californian explorations into looser relationships between social structures, environmental ethics and architectural expression. Yet in many respects his shift is primarily stylistic. While his later architecture shows stronger ties to a much larger world view, he maintains his keen appreciation of climate and the local practice of romanticizing the landscape. Geometric planning and practical, low-budget construction remain the solid foundations of his adventurous yet responsible architecture. Unlike the graded standards of contemporary rating methods, Jones’s sustainability is integral and cannot be added or engineered out at will. His designs are richly credited with values.

Jones’s early work was part of a golden period of local architecture, when a close group of architects, builders and their patrons enthusiastically developed an optimistic postwar modernism that seemed an appropriate form and expression for a young and growing community. Those days are long gone; new priorities dominate. Early mercantile capitalism seemed comfortable within modernism’s forms, but the relationship has gradually inverted. Architecture is now complicit in capital’s project and nowhere more so than in Western Australia. Without a shared theory of place, form and representation, design discourse is marginal, and local architecture and planning are instead preoccupied with maintaining convenience and comfort and with projecting “a look.” While these attributes are easily marketed and administered, social commentators warn that the material affluence of contemporary consumerism masks the relentless erosion of culture. Environmentalists have a similar opinion with respect to nature’s resources and effects.

Remaining true to his humanist roots, Jones’s sense of culture has thickened as he has steered away from the now dominant paradigm. He is clearly a talented and skilled architect who has maintained commitment throughout his career and continues to enjoy an edifying life in architecture. The cool fresh air of inspiration and passion that flows from Raymond Jones’s oeuvre is something that no young architect should miss.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 5 Oct 2011

Words:

Geoff Warn

Images:

Raymond Jones,

Robert Frith

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2011