The curved eastern wall of the Princess Alexandra Hospital, by Cox MSJ. Photograph Marc Grimwade.

Courtyard view of the mental health unit at the Cairns Base Hospital by Hassell. Photograph Robert Gray.

The extent and seriousness of issues facing the delivery of health services in Queensland had reached such a chronic state by the beginning of the nineties that it was necessary to take fundamental, comprehensive and decisive action. A complete overhaul and restructuring of medical services and modes of health delivery necessitated an updating of existing health buildings and the construction of new facilities throughout the state to cope with the escalating demands of the present and to meet the needs of the foreseeable future. The factors to be addressed included the pressures of population growth, the increase in the cost and complexity of medical diagnosis and treatment, advances in medical technology, and the dire state of many hospitals which had suffered from an endemic under-investment in maintenance and upkeep. At some hospitals the situation was so serious that medical staff went to the media with the difficulties that they were facing – the broadcast on national television of a video of rats in the corridors of a major urban hospital being just one incident.

The need to upgrade the health care system received widespread support across political parties and factions, precipitating the largest and most sustained investment in a health-services-led capital works program in Australia. It was decided to completely overhaul the health system and its facilities through an intensive, focused ten-year program of planning, design and construction rather than eking out the necessary changes over a longer period. This ambitious strategy involved significant risks, including a concern that the architectural profession may not have had the capacity or expertise to respond to the demands of such a large scale program within the defined time frame. In 1996 alone, some 250 consultants were commissioned to assist with the delivery of the required facilities. David Jay, the director of the Queensland Health Capital Works Branch, recognises the success achieved by the profession in responding to the needs and expectations of the program. He considers that one of the major outcomes of the program is the acquisition of knowledge and experience that has enabled design consultants to contribute strongly to the debate on health care provision and to challenge the client groups from an expert and authoritative position.

The design of the many projects for new and refurbished facilities was guided by the primary objective to achieve an improvement in health service rather than just the design and construction of health buildings. In meeting this objective, architectural propositions and solutions were to be considered as furthering the delivery of health services, rather than merely resolving issues of form, function and expression. In the case of the major projects, this entailed contributing to the development of the new healthcare models and evaluating their implications for the planning and servicing of the new facilities. The client agencies were multi-stranded, being comprised of coalitions of managers representing different functional entities. They required special skills of the architects in responding to and resolving competing and occasionally contradictory demands and expectations. The need to overhaul the whole of the health delivery system created a need to design for a broad range of building types, including specialised research facilities, special care units, teaching facilities, mental health hospitals, central energy plants, central laundries, aged care units and community-specific care facilities such as the Mt Isa Centre for Rural and Regional Health (Woodhead International). Upgrading the quality of the public health system also prompted the upgrade of many private facilities, which further harnessed the growing expertise of the profession. Some of these were co-located with public hospitals, such as the Holy Spirit Northside by Peddle Thorp which is located on the Prince Charles Hospital campus.

Having commenced in 1992, the program is now drawing to a close with the successful completion of some 50 major projects and over 100 small projects. These range in scale from the $500 million Herston Hospitals project to the $0.5 million spent on Boigu Island. At its peak, some $600 million was expended annually on capital works with a total expenditure of nearly three billion dollars. Close to 99 percent of all projects were delivered on budget and 95 percent were delivered on time. This represents a significant achievement. That there have been no major disputes signals the effectiveness of the overarching management structure and the value of adopting quasirelationship-based contracting for the construction of most projects. Overall, the program has created a robust and flexible infrastructure that is designed to support health services well into the twenty-first century. Flexibility was an essential requirement of all projects, given the certainty that the demand for healthcare will increase over time and that medical knowledge and practice will continue to develop and change over future years.

A particular challenge of hospital design is that the focus is firmly on functionality as measured by the efficiency of healthcare delivery. Hospitals are complex entities that incorporate elements requiring high-level technical support and servicing. The quality of finishes required is high, as is the level of environmental control and the stability of the provision of essential services. Efficient circulation is essential as some 50 percent of the annually recurring costs of running a hospital is consumed by the cost of labour. In the case of the $500 million Herston Hospital project, the annual running cost is $380 million, of which the salaries of staff consumes 70 percent. Poor circulation can dramatically reduce the efficiency of staffing and so reduce healthcare – or increase its cost. The adoption of ambulatory care creates an increase in the throughput of patients which, together with flexible visiting times and open access policies, engenders an active environment in contrast to the closed institutions of the past. Clearly defined orientation and high quality entry spaces are essential to effective wayfinding and to inducing a positive response to the hospital environment.

Despite the focus on operational and technical demands, the program emphasised that the quality of the physical environment for patients, visitors and staff should enhance the health care service. Furthermore, it eschewed the adoption of standardised designs in favour of designs that best suited their particular locations and the needs defined by the client/user teams in each case. Some of the largest facilities, such as those at the Royal Brisbane Hospital, had to be fitted into closely packed and densely built-out hospital sites, whereas others occupied greenfield sites. All projects required integrated project planning that linked service delivery with physical requirements prior to the commencement of design. Response to climate was a primary factor with a view to reducing energy costs, although most facilities are air conditioned if only to ensure a stable and hygienic environment and a reduction in the risk of cross infection. The formation of management teams for each project aided the process of designing to suit each location. Jay emphasises that one of the most important skills required of the design management was that of communication. The task of being briefed by so many specialist disciplines and obtaining productive design input was at times hampered by the poor communication skills of some consultants who failed to convey their ideas to clinicians who, though expert in their own fields, were not necessarily able to fully understand design drawings.

The breadth of the Queensland Health capital works program prevents a comprehensive review at this time and a more detailed analysis is warranted when the program is finally complete and when the various facilities have been in use for a sufficient time to allow teething problems to be resolved. In particular, a review of those projects involving the refurbishment and enhancement of existing buildings, such as the Cairns Hospital A&B Blocks by Hassell, would draw attention to Queensland Health’s achievement in retaining and enhancing existing buildings where they can meet the needs of contemporary health services. The following projects illustrate the range of project types undertaken in terms of size, function and location.

The Princess Alexandra Hospital, Cox MSJ

The sinuous curves of the north-east elevation.

The new entry, signalling a new image for the hosptial.

The water courtyard.

Entry to the education unit.

The chapel.

Link between the entry and the main hospital. Photographs Marc Grimwade.

The Princess Alexandra Hospital became notorious for the poor quality of its physical environment. Most of its facilities had been constructed by the early 1950s and by the ’90s were not capable of meeting the needs of modern healthcare.

Protests by medical staff heightened public interest in the standard of care offered and the redevelopment of the hospital and its overall site were given high priority within the capital works program. A thoroughgoing masterplan and briefing study was undertaken by Hassell and provided the basis of a limited design competition. As the requirements for major hospitals are so functionally specific, they do not lend themselves readily to competitions and this was the only project to utilise a design competition for the selection of consultants. This mode of selection was partly driven by public awareness of the difficulties faced by the hospital and the urban design implications of answering the needs of the new hospital within the confines of the existing site.

The selected architectural group, Cox MSJ, developed the design of the new central building to include 540 of the 760 beds provided by the redevelopment and to house acute care and general inpatient accommodation together with the principal research and teaching facilities.

The design was supported by an overall phasing strategy entailing the decanting and demolition of existing facilities to create sufficient site area. The new building inverted the previous circulation of the campus, which followed the circumference by providing a focal hub through which runs a central route linking the principal buildings and spaces. The two linear spines of the central building are linked by bridging spaces to form a deep mat of specialist accommodation penetrated by two courtyards. The long, serpentine curves of the north-east elevation offer a distinct contrast to the indifferent and intimidating quality of the original buildings. The introduction of natural light into the depth of the building and the shading of windows provide a measure of passive environmental control. The entry is regarded as a particularly successful space and has been fundamental in overturning the legacy of the desultory image of the original building. In answering the urban design agenda, the new hospital has created a positive image for the Princess Alexandra Hospital as offering a high standard of care for the patients matched by an environment providing both respite and amenity.

Project Credits

Princess Alexandra Hospital

Architect Cox MSJ. Mechanical/Electrical/Fire Engineer WBM Bassett Joint Venture. Structure and Facade Engineer Ove Arup & Partners.

Hydraulic Engineer McKendry Rein Petersen. Lifts WBM Bassett Joint Venture. Acoustics Ron Rumble. Kitchen Food Services Design. Quantity Surveyor Rider Hunt. Contractor (Structure) John Holland Constructions. Contractor (Fabric & Fitout) Baulderstone Hornibrook. Client Queensland Health. Project Director Higgs & Associates.

Townsville Hospital, Woods Bagot

Aerial view. Photograph Cameron Laird.

South elevation of the ward building, seen from the university ring road.

The courtyard between the acute building, on the left, and the ward building on the right.

The main entrance porte cochere on the northern side.

Looking west along the north elevation, with its dramatic external stairs, towards the emergency entrance.

The internal atrium, looking west alone the level 2 corridor.

Night view of the main entrance porte cochere. Photographs David Sandison.

The new Townsville Hospital, one of the largest outside Brisbane, provides 425 beds and offers a general acute level of medical support. It is a freestanding development replacing the original facility in the centre of the city. The model of care developed for the hospital clusters clinical services with the co-location of inpatient and outpatient functions. This increases flexibility by bringing the clinical services into a direct relationship with the related bed spaces. The interconnection of the four key buildings creates a deep plan, given a strong order by the clarity of the circulation patterns. The four-storey, naturally lit, atrium-cum-arcade, running from east to west through the length of the main building, anchors the horizontal and vertical circulation and gives an order to the overall pattern of circulation. The designation of this space as “open space” assists with fire evacuation and considerably increases the potential flexibility of planning to accommodate future changes. The ambition to create a welcoming and enjoyable environment is sustained by the emphasising the locations of the entry and main stairways by strongly pronounced, super-scaled, blade walls and by the use of bright colour to punctuate the spaces.

A simplicity of construction is suggested by the extruded shed-like forms, which are enlivened by glancing intersections in plan and by deeply projecting roofs and sun shading. These serve to assist with the control of solar penetration and heat gain and to evoke an association with regional building traditions. The generous, shaded portico and the lively composition of the principal elements provide a lively and engaging character in complete contrast to the original Townsville Hospital. The design signals the changes made to healthcare and offers an open and accessible centre that overcomes the overwhelming presence that could have resulted from a facility of this size if governed by less thoughtful design.

Project Credits

Townsville Hospital

Architect/Lead Consultant Woods Bagot.

Architectural Subconsultant Ralph Power Associates. Quantity Surveyor Rawlinsons.

Structural Engineer Bonacci Group, Halliburton KBR. Civil Engineer Halliburton KBR. Services Engineer Lincolne Scott Australia. Hydraulic Engineer Steve Paul and Partners. Project Director Burns Bridge Australia. Building Surveyor, Risk Manager Project Services. Programmer Tracey Brunstrom and Hammond. Managing Contractor John Holland Group.

Comprehensive Cancer Research Centre (QIMR), Bligh Voller Nield

Street elevation, with the link bridge to the Bancroft Centre to the left.

The continuous plinth of textured brick at street level.

Lightweight metal cladding emphasises the technical nature of the research facility. Photographs David Sandison.

The Queensland Institute of Medical Research is the State’s premier medical research facility with an international reputation for its contributions to advances in medical knowledge. The Comprehensive Cancer Research Centre is a 13,000 square metre extension of the existing centre, co-located with the Royal Brisbane Hospital on the densely packed Herston medical precinct. The ten-storey specialised research facilities include special units for clinical trials, five floors of research laboratories supporting the study of cell manipulation and fermentation activities and one level for activities relating to epidemiology and bio-statistics. Although not a facility requiring public access, it occupies one of the most visually prominent sites of the medical precinct and establishes the boundary along Herston road close to the major intersection with the Bowen Bridge Road.

The scale and bulk of the building is reduced by the composition of the intersecting volumes of its key elements.

The laboratory levels are fully glazed to reveal and emphasise the primary purpose of the building. The use of lightweight, gridded metallic cladding emphasises its technical function and the overall form is linked to the scale of the passer-by a continuous plinth of textured brick.

Project Credits

Comprehensive Cancer Research Centre

Architect Bligh Voller Nield Wilson Architects joint venture—project team Phil Tate, Chris Clarke, Mark Grimmer, Anthony Ogden, Geoff Hehir, John Thong, Robert McAdam, Hamilton Que, Warwick Allen, Richard Sale, Michael Hartwich, Michael Tanner, Michael Rogers, Michael Obrien. Project Manager Project Strategies and Solutions. Quantity Surveyor WT Partnership. Structural/Civil Engineer Robert Bird & Partners. Mechanical Engineer WBM Consulting Engineers. Electrical Comms Barry Webb & Associates. Hydraulics McKendry Rein Petersen.

BCA Consultants TASPM. Managing Contractor Baulderstone Hornibrook. Artist Eugine Carchesio.

Client Queensland Institute of Medical Research.

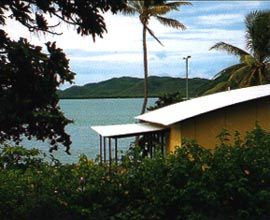

Thursday Island Hospital and Community Health Centre, Cox MSJ.

One of the most remote projects within the program is the Thursday Island Hospital, way up in the Torres Strait. In part, the impetus for the project came from the disaffection shown by the Islander community for the earlier hospital that had failed to address the cultural needs of the community. The new hospital is comprised of interconnected, verandah pavilions, linear in plan and with gently curved roofs that offer openness to both view and breeze.

This openness, matched by a flexible policy for visiting hours, offers a less intimidating and less institutionalised resource that invites the community to regard the hospital as a social focus as well a place of medical care.

This invitation is further emphasised by the design of the main entrance foyer which is an open breezeway framing views to the aqua-blue of the sea beyond.

Although a small hospital with some 34 beds, it is a significant resource for the island community and offers a structure of healthcare and a physical environment that is more relevant and accessible than the previous, more conventional and prescribed model.

Project Credits

Thursday Island Hospital and Community Health Centre

Architect and Planner Cox MSJ. Client Queensland Health. Project Director Higgs & Associates. Project Manager Q Build Project Services. Contractor Barclay Mowlem. Civil Structural, and Hydraulic Engineer Connell Wagner. Mechanical and Electrical Engineer Gutteridge Haskins & Davies. Kitchen Food Services Design.

Clermont Hospital, Fulton Trotter and Partners

Entrance to the Clermont Hospital.

The admissions counter.

Courtyard space between the old and new blocks. Photographs Richard Stringer.

The interest in the Queensland Health program has inevitably focused on major projects in the urban centres. Yet, a key feature of the program has been its encompassing of all scales and forms of healthcare across Queensland. The practice of Fulton Trotter and Partners has specialised in the design of public buildings in many of the smaller and far flung regional centres and country towns. They have returned to some of the hospitals designed in the fifties by a previous generation of the practice, to add new facilities and refurbish the existing buildings as part of the health services program. These projects include hospitals at Barcaldine, Emerald and Clermont.

The most remote of these townships is Clermont, which has been resuscitated by the re-opening and modernisation of the nearby Blair Athol open-cut coal mine. The project involved the stripping out of miscellaneous additions to the original buildings, refurbishing the 1950s core building, extending the operating theatre and constructing an aged care cottage with a treatment similar to the original buildings. A new inpatient wing has been added parallel to, and to the north of, the existing hospital, creating a series of sheltered gardens and courtyards between the two. They are linked by a new main entry, by the administration offices and by connecting passageways. The existing building was restructured to house emergency, outpatients, medical imaging, dental and allied health facilities. A generous verandah along the length of the new wing offers sheltered outdoor seating while shading the inpatient accommodation. Further shading protects the western elevation and these two measures help to reduce the air conditioning load.

The new wing emulates something of the scale of the original while employing mono-pitched roofs and a mixed palette of masonry veneer and metal cladding that clearly distinguish it from the original. The construction system of a simple steel frame and suspended concrete floors offers flexibility both of layout and of service distribution. Although one of the smaller projects in the program, this hospital provides the primary healthcare for the town and its region. It now offers a high standard of medical services in a hospital that is both welcoming and relatively informal. The care taken to design a range of open and enclosed social and waiting spaces increases the sense that this facility is in itself hospitable and intended to serve and sustain its community ››

Project Credits

Clermont Hospital

Architect Fulton Trotter and Partners—design architect Mark Trotter; project architects Robert Wesener, Nicole Thomas; health planners Roger and Jane Carthey; design team Winfried Sitte, Kylie Forbes, Greg Isaac, Justine Ebzery; specification Stephen Trotter; interior design Clare Bennett. Structural Engineer Connell Wagner.

Services Engineer Bassett. Hydraulic Engineer McKendry Rein Petersen. Landscape Architect Belt Collins. Quantity Surveyor Mitchell Brandtman.

Builder Evans Harch. Project Director Burns Bridge. Procurement Manager Project Services.