In the postmodern 1980s, Maggie Edmond and Peter Corrigan of Melbourne architecture practice Edmond and Corrigan, along with Norman Day and Gregory Burgess, sought a new way to represent their work. Photographer John Gollings achieved this by manipulating reality to help illustrate the theory behind the designs.

A few years ago, my partner and I wanted to rebuild our family home in Melbourne’s northern suburbs. I’m talking proper far-northern suburbia. Not Brunswick or Fitzroy, but a terrain complete with industrial badlands and identikit postwar homes that have had only one owner. We wanted to hire a firm of inner-city architects for our new design but soon received a reality check.

“No-one will work out there,” came the warning. “It looks bad on the folio.”

In the end, we hired building designers, who not only respected our budget but also acknowledged the terrain for what it was: a low-cost pathway for new families to enter the housing market. They were glad to show their faces out there and we appreciated their empathy and understated skill.

Since we arrived, through the mysterious forces of gentrification, our area has been transformed (including the sneaky appearance of inner-city architecture types) and I’m left with some questions. Why is it always back-to-front? Why do architects hate the suburbs?

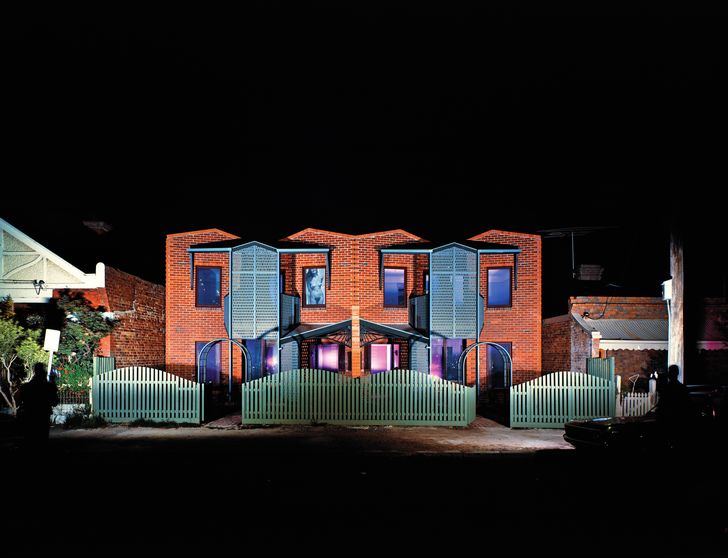

Station Street Housing, Carlton, by Gregory Burgess Architects for the Ministry of Housing (1983).

Image: John Gollings

In recent years, there has been much debate about the value of building designers versus architects, but whatever your view on the former, their work exposes an undeniable truth: building designers know far more about this vast market – the countless social, financial and psychological motives that bring people to the suburbs – than architects.

Suburbia is a longstanding wound. In 1933, the International Congress of Modern Architecture dismissed the suburbs as “a kind of scum churning against the walls of the city.” But today, if there’s one thing the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us, it’s that such posturing doesn’t cut it anymore.

Businesses and politicians want office workers to return to the CBD, but the shift toward remote working revealed an alternate reality. Many workers don’t want to go back. They’ve found that less commuting and office time has led to increased productivity and work-life balance. The perception is that there’s more time to ride the bike, walk the dog and explore the neighbourhood. And since most of us live in the suburbs, this former crucible of scum- churn would seem to have had a soul transplant.

Fitzroy House by Norman Day (1983).

Image: John Gollings

The reality is somewhere in between. If your job is super busy, or you’re a workaholic or have kids to juggle, then the Covidian home annihilates time. It has long been the freelancer’s bugbear. When you work from home, how do you switch off? With no commute to mark the end of the working day, how do you manage the expectations of bosses and colleagues?

It doesn’t help that many remote workers now toil away in bedrooms, garages and kitchens, a consequence of shoehorning existing design into unforeseen cultural use. When work bleeds into the home, the psychological toll can be exacting.

Although such problems have taken the gloss off remote working, surveys indicate that many people want their jobs to maintain at least a hybrid office/ home arrangement. That’s where architects, with their ability to conceive entire worlds and all the moving parts needed to complete them, are in a unique position. By rethinking our homes as multi-functional spheres, architects can help us regain time.

Toward the end of 2020, the Australian Institute of Architects put out a call. The Institute wanted architects to help hospitality venues in Melbourne’s CBD embrace COVID-safe measures like outdoor dining. But why should zombie urbanism receive the kiss of life when traffic is flowing in the other direction?

Where are the incentives to recalibrate suburbia? Given the new weight of expectation, such a program would re-imagine more than just the home. It would connect it with its immediate surrounds, encouraging us to roam around the suburbs with the same swagger as we would on our lunchbreak in the city.

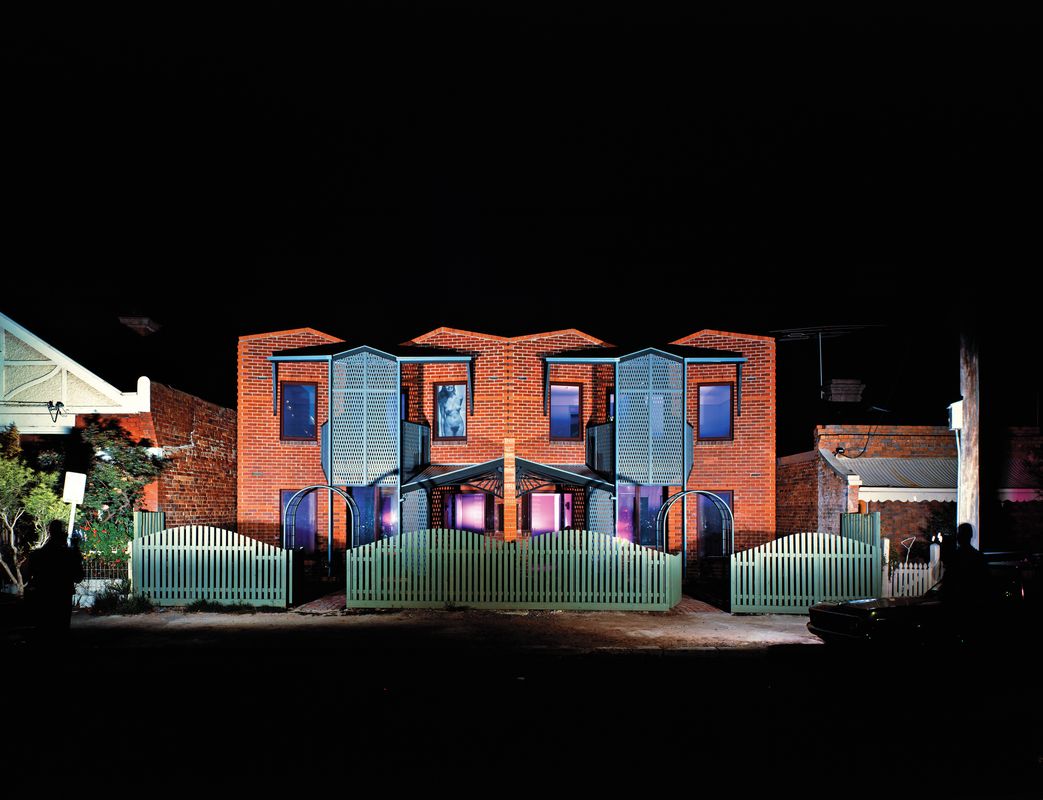

Freedom Club, Church of the Resurrection by Edmond and Corrigan (1978).

Image: John Gollings

There’s a lot to incentivize, given that not all Australian suburbs are equal. A recent ABC report into mental health issues found that, predictably, those in privileged areas are less likely to suffer from such an affliction. In poorer areas, mental health problems are concentrated, largely because of the effort required to seek treatment. There might be no funding for a facility in that region and public transport might be too infrequent to go elsewhere.

If we’re serious about activating suburbia to sustain the social shifts that COVID has wrought, then such divides must be met head-on. Studying mobility can tell us much about where to begin.

For example, in Australia in recent years, bicycle sales have been steadily climbing. During the pandemic, they went through the roof once public transport was deemed unsafe and cars were mothballed without all those CBD trips to undertake. Surprisingly, now that we’re through the worst of it, traffic on some major roads is actually heavier than before the crisis began. Use of public transport is still down, but all those new bikes look set to rust as owners bring their cars back out of the garage. It would be a shame to waste the momentum.

Good design can holistically link our homes with work, health and leisure pursuits. It can reinvigorate areas where public transport is limited and cars are unaffordable. If we design with foresight, we might sustain interest in alternative transport instead of slipping back into destructive modes.

Caroline Chisholm Homes, Keysborough, by Edmond and Corrigan (1980).

Image: John Gollings

Let’s face it: cycling on Australian roads can be intimidating. Bike lanes vanish without warning, dumping hapless riders into heavy traffic, and when vehicles are held up in car-obsessed Australia, blood runs hot. In the heat of the moment, motorists see cyclists as scofflaws flaunting some weird privilege, while riders imagine cars as metallized death stalking their rear wheel.

By contrast, at the Bicycle Architecture Biennale in Amsterdam, the projects on show cleverly integrate cycling with the built and natural landscapes. Innovations include an eight-kilometre elevated cycleway in Xiamen, China; a seamlessly integrated parking garage for thousands of bikes in Utrecht, the Netherlands; and a concrete cycleway scything through a pond in Limburg, Belgium. But whenever it’s suggested that Australia should adopt a similar philosophy, the counterargument is invariably about the tyranny of distance and our reliance on cars to overcome it. It’s lazy, protectionist thinking and we deserve better.

Since COVID began, a slew of articles have appeared urging architects to rethink their profession. Often, these call for “critical thinking” and “deep reflection,” but the time for navel-gazing is over. Radical creativity is sorely needed: the ability to peel back the veneer and empathize with lived experience. Take the architects who drove the development of all those innovative cycling projects. They’ve rebranded themselves as civic subjects and that’s a fine start.

To return to the home, in architectural terms there’s an added benefit to studying patterns of movement. When mobility changes, so does the home. Postwar Australian suburbs and homes were built to accommodate the car and all it represents, but what might they look like once the car loses primacy? Future changes in building typology might derive as much from psychological mutations as from physical impressions. After all, riding a bike is a very different experience from driving a car, while remote working is a form of inverse mobility: a return to the source.

Caroline Chisholm Homes, Keysborough, by Edmond and Corrigan (1980).

Image: John Gollings

When Howard Arkley produced his lysergic portraits of Australian suburbs, he conceived them that way because the aesthetic spoke to the underlying truth of how people lived their lives. They had made a home in unfashionable suburbia, sometimes under difficult circumstances, but to them it was wonderful.

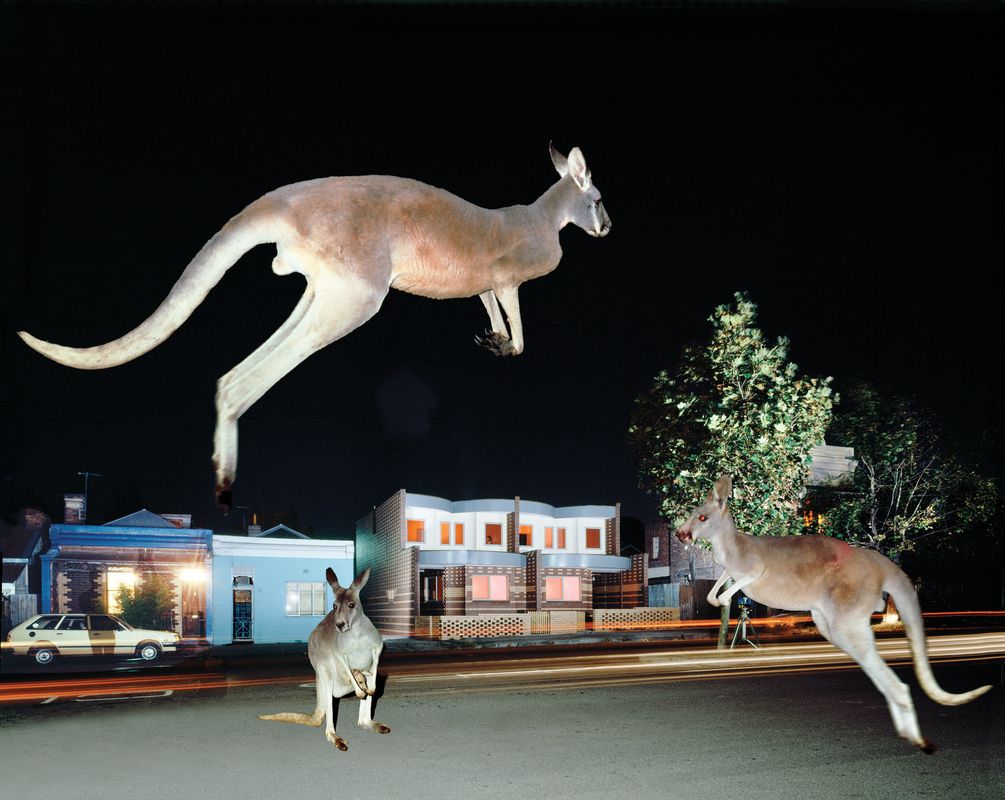

Similarly, John Gollings’s early photographs introduce a playful surrealism into suburban snapshots. Kangaroos hop down main streets, children fly through the air outside churches and people dance in nightclubs bathed in other-worldly light. These colourful bursts of activity are an expression of mobility in its most joyous form. Citizens – not buildings – are the drivers in activating suburbia and architecture is positioned as a complement to the way humans negotiate time and space.

In Beautiful Ugly, a retrospective of Gollings’s work, Joe Rollo writes that the photographer has been patronized by architects for distorting perspective and digitally erasing material imperfections. But no one viewing Gollings’s early suburban works would argue that they are realist. Perhaps they are magic realist.

In literature and film, the genre of magic realism presents an essentially prosaic view of the world while introducing fantastical elements. It unlocks hidden layers of everyday life with a shift in perspective. That aesthetic is intimately related to architecture and placemaking. If infrastructure is concerned with the basic organizational framework needed for an area to survive, then liveability must be embedded from the bottom up.

Lifting the veil on the new suburbia, what might we find? If all goes well, perhaps a terrain where community health, social justice and cultural mobility are inextricably linked with work, home and leisure – and equally weighted, too.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 30 Sep 2021

Words:

Simon Sellars

Images:

John Gollings

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2021