John Andrews at the University of Melbourne symposium, 2012.

John Andrews is arguably the most internationally significant Australian architect of the past half-century. He may not have a Pritzker, but his list of projects is remarkable: University of Toronto’s Scarborough College (first stage completed 1963); African Place for Expo 67 in Montreal (1967); Miami Seaport Passenger Terminal (1970); CN Tower in Toronto (1976); Gund Hall for Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design (1972); the Cameron and Woden offices in Canberra (1976 and 1981); Sydney’s American Express Tower (1976); a slew of university buildings in Canada, the US, and Australia; and convention centres and hotels across Australia’s state capitals.

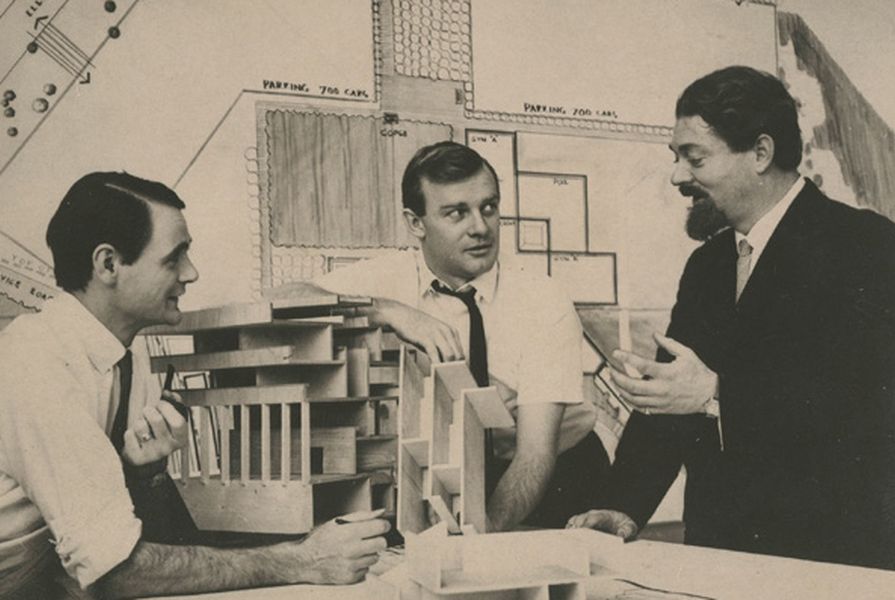

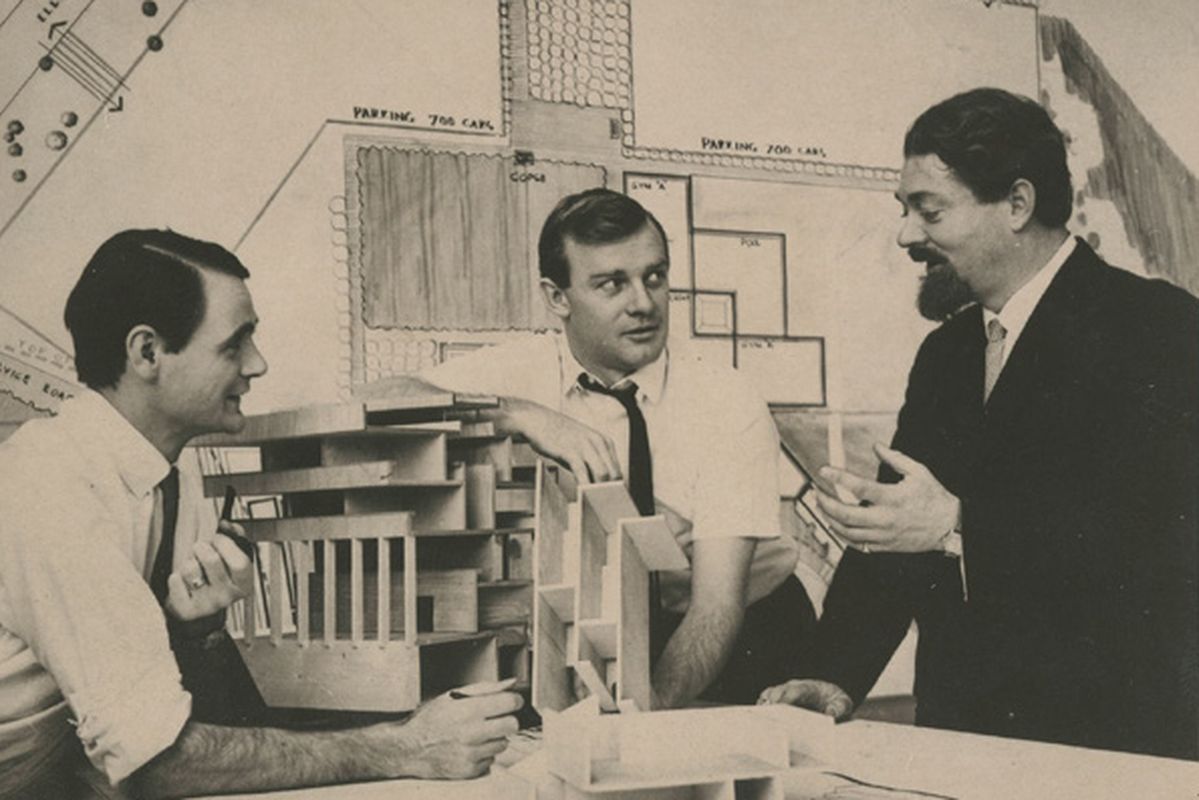

After completing a Bachelor of Architecture at the University of Sydney in 1956, Andrews undertook graduate studies at Harvard University under José Luis Sert. Along with three Harvard colleagues he was placed second in the 1958 international competition for Toronto City Hall, as significant at the time as the Sydney Opera House competition had been the previous year. As in Sydney, the Toronto jury deliberations were dominated by Eero Saarinen, who in both cases drove the selection of a Scandinavian architect. Andrews was recruited by the local office responsible for realizing Finnish architect Viljo Revell’s Toronto design, and they formed a close friendship. After City Hall was completed, a period of travel and a short return to Sydney were followed by independent practice in Toronto, and teaching at University of Toronto.

Andrews’ big break came with the Scarborough College design for the university, as part of its plan for suburban expansion in the 1960s. Scarborough was widely published on completion, and made Andrews’ international reputation. Much university work followed, including student residences for the new University of Guelph, a library for University of Western Ontario, a fine arts building at Smith College, and another for Kent State University. The most prestigious of these projects was Gund Hall for Harvard University: Andrews seemed to have been selected by Sert, out of all his former students, to get the nod. Sert’s architectural practice had itself done several Harvard buildings, and the only other architect he was directly involved in appointing for the university was Le Corbusier (his Carpenter Center is just down Quincy Street, near Gund).

John Andrews Gund Hall, Harvard University, 1972. I

Image: Paul Walker

Andrews returned to Australia after being drafted by Sir John Overall, head of the National Capital Development Commission, to apply his talents in the rapid expansion of Canberra – Cameron Offices at Belconnen, a complex for four thousand federal government bureaucrats, followed. Andrews also advised on the selection of architects for other Canberra projects, and was a juror for the 1979 competition for the design of Australia’s new Parliament House. Andrews’ Sydney office undertook work throughout Australia and continued to have an international profile, winning the 1980 competition for the design of the Intelsat building in Washington, DC.

When Andrews was at the height of his reputation, Australian architectural writers Philip Drew and Jennifer Taylor were important in asserting his significance both globally and in the local scene. As well as undertaking her own analyses of Andrews’ work in her book Australian Architecture Since 1960 (1986), Taylor collaborated with the architect on John Andrews: Architecture a Performing Art (1982), which recorded his thoughts on his design approach and achievements. A new research project on the work of Andrews is currently underway to build on these writings of a generation ago. The project involves scholars at five universities in Australia, Canada and the US (Paul Walker and Philip Goad, the University of Melbourne; Antony Moulis, the University of Queensland; Peter Scriver, the University of Adelaide; Mary Lou Lobsinger, University of Toronto; and Paolo Scrivano, Boston University).

John Andrews Sydney Convention Centre, Darling Harbour, currently under threat of demolition by the NSW Government.

Image: Danny Kildare

It is timely to look again at the work of Andrews, and indeed the work of his whole generation of Australian architects. Many of the significant buildings of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s are now at an age where refurbishment is necessary, and for many owners replacement is an easy option. Often original client organizations or their activities have changed. In other cases, projects by the Andrews team were designed to be part of an anticipated broader scheme that did not eventuate. The most poignant example is the Cameron Offices, which were supposed to connect to Belconnen’s commercial centre, which was subsequently built on a site different to that of the original scheme. Ideologies also change: the partial demolition of Cameron is an outcome of a view that “the market” should be engaged in the provision of office space for Canberra’s civil servants.

Looking at Andrews’ buildings, however, reminds us that whatever the opportunities for architectural design in the digital era are, we are never again going to be able to build with the sense of generosity, optimism and sheer concrete weight (literal and phenomenal) that were available to him. The banality of current office building architecture in Canberra makes the loss of much of the Cameron complex all the more grim.

Supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council, the current research project will investigate this history of Andrews’s architecture since the significant scholarship by Drew and Taylor. Serious reassessments of postwar modernism, and now of the transitional period of the 1970s, allow Andrews’ work to be considered against the broader architectural currents of the period. But the project also has the ambition of discovering more about how the work of the office was actually done, the story of the projects before they became pristine images in the architectural media, their engagement with innovative planning and spatial composition techniques, environmental performance initiatives, procurement strategies, and the office culture that made this possible. Both the Toronto office in Colborne Street, and the Sydney office at locations in Palm Beach had the reputation of informality, but they were highly productive and efficient.

A symposium at the University of Melbourne in October 2012 brought together members of the research team, many of the key players in the Andrews Sydney practice, and John Andrews himself, to workshop these ideas. Such a meeting departed somewhat from the historian’s conventional practice of interacting with informants through lengthy individual interviews, but had the distinct advantage not only of economy but also of making the gathering of information an engaging public event. And something of an Andrews reunion. Watch this space for further developments.

Source

People

Published online: 28 May 2013

Words:

Paul Walker,

Philip Goad

Images:

Danny Kildare,

Paul Walker,

Philip Drew,

Sophie Hill

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2013