The wharves prior to redevelopment.

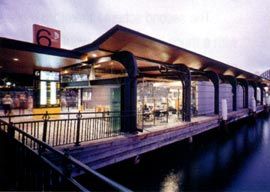

Overview of Wharf Six. Image: Brett Boardman.

The passenger terminal shortly after its 1988 redevelopment, showing the orange skeletal frame and the striking outdoor escalators at its southern end. Image: John Gollings.

The new public stair, replacing the escalator. Image: Adrian Boddy

The northern end of the terminal. Image: Adrian Boddy

View through the terminal at ground level. Image: Adrian Boddy

Overview of the redeveloped terminal seen across Sydney Cove. Image: Adrian Boddy

View over Sydney Cove to the harbour from the viewing area at the mid-point along the Cahill Expressway. Image: Brett Boardman

Looking along the expressway towards east Circular Quay. Image: Brett Boardman

View west, showing the new lift connecting Circular Quay to the Cahill Expressway. Image: Brett Boardman

The significance of Circular Quay cannot be underestimated. To Indigenous Australians, “Sydney Cove marks the invasion point, and the point from which the decimation of the Aboriginal people began”. To postwar immigrants Sydney Cove is Australia’s equivalent of Staten Island. For Sydneysiders it is one of the city’s major transport hubs, where many thousands of people converge as part of their daily routine. For visitors it is, along with The Rocks and the Opera House, one the places that must be visited. It is perhaps Sydney’s only truly great public space – that is, “great” in terms of international significance. It may not be a place for mass rallies or demonstrations, but it is the centre of Sydney’s great public celebrations and forms a natural amphitheatre within which to view Sydney’s three chief icons, the Opera House, the Bridge and the harbour.

In the Minister’s Forward to the Sydney Cove Waterfront Strategy – Master Concept Design Report, the Hon Ron Dyer MLC proudly announces that the report had “gained widespread support from the twenty-five government and twenty non-government stakeholder organizations who have been involved in the preparation of the strategy”. This says a lot about the difficulties in dealing with Circular Quay. There are so many groups to appease, all of whom have the ability to stifle and obstruct, with the result that significant changes can seem beyond the possibility of a consensus.

The last major upgrade at Circular Quay was completed in time for the Bicentennial celebrations in 1988. A number of prominent architects were engaged under the overarching umbrella of the NSW Government Architect to refurbish the Overseas Passenger Terminal, the Ferry Wharves, the pedestrian journey out to the Opera House and to complete an all-encompassing urban overlay of paving, signage, lighting and the like. The project was a great success and received from the RAIA the Lloyd Rees Award for Urban Design and the national Civic Design Award, along with a national Merit Award for the Overseas Passenger Terminal.

Ten years later, in the lead up to the 2000 Olympic Games, Minister Carl Scully decided that Circular Quay had become a little tired and shabby and was again in need of an upgrade. So in 1997 the NSW Government commissioned the Department of Public Works and Services to complete a concept design report. The study area was divided into seven zones, stretching from the Overseas Passenger Terminal on west Circular Quay around to the south-east corner of the Quay. It included the wharves and the Alfred Street precinct but specifically excluded east Circular Quay – at the time a highly contentious site awaiting approval for redevelopment.

The concept design report was very general in its recommendations, stating four broad “key concepts” and a series of “principles” to form the basis of future projects. This generality was necessary if it was to gain any form of sign-off from the many stakeholders and for any individual projects to proceed. Three main projects which emerged from this process have now been completed: the redevelopment of the Sydney Cove Passenger Terminal; the redevelopment of the Circular Quay Wharves; and pedestrian access to the Cahill Expressway, including improvements to the Circular Quay Station.

Circular Quay Wharves

The design strategy here was simple and difficult to disagree with – to clear away the clutter, to remove all that was not required to be on the wharf and to open up to the magnificent views to the Harbour. The first Development Application lodged removed the retail and relocated it under the Circular Quay railway line within a series of lightweight retail pods. However this strategy was opposed by the Central Sydney Planning Committee, who did not want additional built forms blocking the ground plane connection between the wharf zone and the Alfred Street zone.

The second scheme therefore moved the retail outlets back onto the wharves, but with a much rationalized layout that concentrated built form to one side, and relocated most of the operational activities within the two-storey Wharf Three. The other side of each of the wharves and the centre zone were to remain open.

But during the development of the design a perceived need for dual ticket booths on each wharf emerged (despite the fact that only one is used). As a result, most of the wharves have some form of structure and retail parked on both sides. Wharf Six remains closest to the vision intended, though the detailing of the frameless glass screens to the sides seems over-designed in amongst the robust and straightforward expression of the base wharf structure. Lifting up the roof eaves, so that they now appear to peel away from the steel portals, has been an elegant and clever strategy, and the consistent and clear signage strategy has improved the legibility and branding of the zone. In the end, however, the works completed have not really fulfilled their visions, even though they were modest and reasonable in their breadth and were clearly pushed heavily by the Government Architect. This says much about the frustrations of working at the Quay.

Sydney Cove Passenger Terminal

Most architects might wonder why there was a need for a major refurbishment to an award-winning building that had only been completed ten years. There were a number of perceived problems with the original building, such as the maintenance of the external escalators and the visual barrier that the building presented to pedestrians wanting to explore north towards Campbells Cove. However, the real outcome for this project has been the desired retail expansion and associated financial return to the Sydney Ports Authority. This drive for retail expansion seems to have overtaken the redevelopment to the extent that much of the delight of the 1988 design has been swept away.

The commercial project did present the opportunity to develop and apply some considered urban design principles: opening up the visual link to Circular Quay West by pulling back the western alignment of the building at ground level; activating and partially pedestrianizing the Circular Quay West roadway and ensuring visual transparency across the building at ground level. However, the success of these principles will depend in part on whether the existing commercial outlets along Circular Quay West choose to orientate to the east and thereby help activate the space. For the moment at least this is still not an entirely inviting place to wander through and it is doubtful that it will ever be able to compete with the water side of the terminal, which is open for public access on the 300-odd days of the year that a ship is not berthed.

But it is the southern end of the redevelopment that is particularly disappointing in its execution. The tectonic expression has little to do with the remainder of the building, which had a romantic maritime expression, symbolic of its function. The new public stair on the western alignment is poor compensation for the loss of the escalators, with their angled invitation to public exploration of the building platforms, and much of the original exposed orange-coloured skeletal steel frame has been excised and rationalized. At the other end of the building, another set of public stairs has been removed and rebuilt internally, as though swallowed by the expanding restaurants. This also interrupts the existing public pedestrian route along the raised roadway.

Cahill Expressway and Circular Quay Station

The works to the Circular Quay Station were also about clearing away clutter and opening up the views to the Harbour. Advertising hoardings between the tracks were removed, and the solid framed balustrade on either side of the central masonry enclosure was replaced with bronze stanchions and toughened glass.

Direct pedestrian access to the Cahill Expressway from Circular Quay was provided though two glass-encased lifts placed at the eastern corner of the Quay. The existing pedestrian path was narrow, however the Government Architect managed to convince the Roads and Traffic Authority to allow two metres to be trimmed from the roadway and the path was widened. Midpoint along the path, a raised platform provides a sheltered viewing area and interpretative panel display. The path has been extended across Macquarie Street, with a piggyback section to the existing bridge, and now connects into the edge of the Botanic Gardens. Apart from the expense of the lift, this is a modest design that builds on existing aspects of the Quay and provides an important new link within existing pedestrian networks.

Conclusions

To date, little of real design consequence has been implemented from the Waterfront Strategy. This may seem harsh, but it could be strongly argued that little needed to be done anyway – the Quay already worked extremely well. However, other factors – commercial pressures, the difficulty of obtaining agreement from the myriad stakeholders and so on – have also had a negative impact on the outcome. This is of concern. The sheer importance of the Quay should override the commercial pressures that have devalued the architecture of the Overseas Passenger Terminal and should facilitate more complete adoption of the vision for the wharves. There will always be occasions when the greater urban design considerations will clash with the objectives of one or more of the Quay stakeholders. Without the ability to control and direct the stakeholders at the Quay, there is a risk that the kinds of positive changes that are able to be wrought will amount to little more than occasional “tinkering” and stylistic redirections.

Perhaps the root of Circular Quay’s problems lie in the way in which the responsibilities for decision making are divided amongst various groups that each have vested interests. Concentrated and layered within the Quay is perhaps the most complex array of problematic stakeholders that could be contemplated. While there appears to be considerable goodwill amongst these stakeholders to improve the Quay, there is actually no single authority who has the responsibility for the entire Quay. Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority (SHFA) are officially the place managers, but their role is limited to ranger services, cleaning and waste removal, planning functions, tenant and asset management, event facilitation and precinct marketing. Planning NSW are the approval authority, but they can only respond to proposals, not initiate them.

Major design initiatives at the Quay are generated at the political level when there is a perceived need for an upgrade, such as in the lead up to 1988 and 2000. In both cases the Government Architect managed the upgrade works, and battled as best it could through the long-winded process of stakeholder approvals. While improvements can be managed this way, it is a piecemeal approach that does not always result in the best possible outcomes ›› The future of Circular Quay will probably continue to be a future of regular upgrade works spaced approximately 10 to 15 years apart. They will be in the realm of clean-ups – as the carefully considered design concepts laid in place every 10 to 15 years gradually become diluted by the drip, drip, drip of parsimonious retailers, obstinate authorities and indolent regulators. Each clean-up will be tempered with the flavour of its time, as part of the general circular nature of design conformities. So along with the predictable build-up of accretions that must be chipped away, like barnacles from a boat, there will also be a ritual removal of items from the previous “clean-up” that are no longer viewed in a positive design light. For anything visionary and lasting to ever happen at Circular Quay, (and that is not to say that anything visionary is actually required), there would need to be a change in how decisions are made regarding the Quay. Otherwise “tinkering” will continue to be the fate of the Quay.

Credits

- Project

- Sydney Cove Waterfront Strategy

- Design team

-

Peter Mould, Leonard Morgan, Melissa Ward, Jason Border, Linda Gosling

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Credits

- Project

- Sydney Cove Passenger Terminal

- Design

- NSW Government Architects Office

Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Project Team

- Chris Johnson, Peter Mould, Lindsay Clare, Kerry Clare, Lynn McCaig, Laurance Neild, Neil Hanson, Martin Langham, Phillip Walker, Nadia Brogan

- Consultants

-

Design development/documentation

Bligh Voller Nield

Retail consultant NSW Government Architects Office

Signage consultant NSW Government Architects Office

Technical inspection Bligh Voller Nield

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

- Client

-

Client name

Sydney Ports

Credits

- Project

- Circular Quay Wharves

- Design

- NSW Government Architects Office

Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Project Team

- Peter Mould, Kerry Clare, Lindsay Clare, Graham Thornburn, Rod Drayton, Andrew Duffin

- Consultants

-

Design development/documentation

Noel Bell Ridley Smith

Technical inspection Noel Bell Ridley Smith

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

- Client

-

Client name

Waterways Authority/Sydney Ferries

Credits

- Project

- Cahill Expressway

- Design

- NSW Government Architects Office

Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Project Team

- Peter Mould, Annie Tennant, Michael Harvey, Graham Thornburn, Rod Drayton

- Consultants

-

Documentation

Noel Bell Ridley Smith

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built