One of my favourite statements about the making of the city is an effusive English translation of a quotation from the seminal 1753 essay “Observations sur l’architecture” by Marc-Antoine Laugier: “Regularity and strangeness are needed, correspondences and antitheses, accidents that vary the picture, great order to the details, but confusion, clashing and tumult in the whole.”1

The office of Hill Thalis Architecture and Urban Projects has been located on the top floor of a five-storey brick warehouse, in the inner-Sydney suburb of Surry Hills, for the last decade. In the tracks we make between our studio and local cafes, the bookshop, the park, and the magnificent Central Railway Station completed in 1906 by New South Wales Government Architect Walter Liberty Vernon, the members of our team have become both intuitively and very consciously aware of the “correspondences and antitheses” that suffuse this rich urban place in our city.

Common and cut bricks and perfunctory concrete sills in the ‘sides and backs’ of the city.

Image: Laura Harding

We scrutinize and assimilate the junctions, transitions and misalignments of urban buildings the way a carpenter might study the intricacies of a dovetail joint. Often it is the meeting of two bricks, a gap between emphatic structural piers, an inset downpipe, or the aloof misalignments of adjacent cornices where the cadastral pattern of the city plan, surveyor’s marks and ownership patterns are translated vertically, and the face of the city is made.

Common and cut bricks and perfunctory concrete sills in the ‘sides and backs’ of the city.

Image: Laura Harding

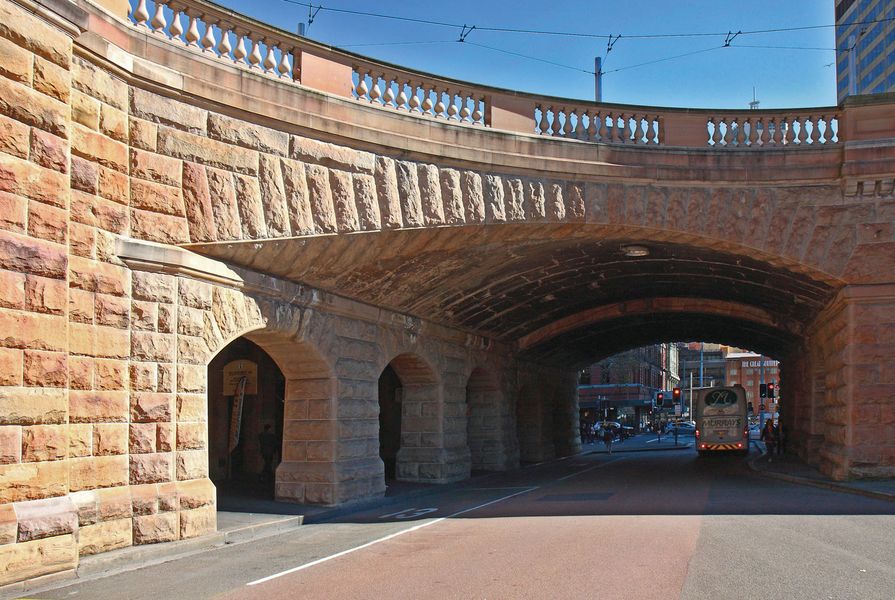

There are, in the best of buildings, moments of exquisite craft that articulate these junctions. It has become customary for members of our practice to stop outside Central Railway Station, and attempt to reconcile the geometric sophistication with which Vernon’s team was able to so nimbly peel the tooled sandstone blocks – each unique in pitch, depth and height – to span the roadway, trim the concrete barrel vaults and slip effortlessly into the northern porch with such unified precision.

We dream of moments where we might get to explore an elemental, architectural level of craft as a way of building the city, but more often than not, the making of the city is a significantly different activity. Speculation, commerce and institutional indifference pull time and labour beyond our reach, and we are often left to consider how we can fashion a rich and satisfying urban place without craft as part of our repertoire.

Fortunately, the city is also rich in instruction, and so we look to the laneways. In the sides and backs of the city, anonymous architects have not had the opportunity to design with craft. Rather, direct and unsentimental eyes have forged memorable urban experiences with common and cut bricks, perfunctory concrete sills, the most subtle shifts of depth and the unhurried work of wind and water on surfaces.

It takes slower and less precious eyes to record the detail here: the slightly darker burn of the brick “specials” that allow a rhomboid laneway pier to express the skewed alignment of its hidden boundary; the broken and imprecise placement of common brick that infill the wall face, and which come alive for the briefest moment, just after midday, when the sun strikes down across them; the unconscious patterns of occupation that break the mechanical regularity of steel windows when their wired glass casts incongruously delicate shadows across grimy brick bonds; and the gaping and mysterious quality of dimly lit openings scaled for trucks, wagons and loads.

Hill Thalis recently transformed an old theatre building into urban housing. The Majestic was a tough old brick barn with a brute urban force. Instead of seeking the intricate crafted junctions of a painfully articulated “contemporary” intervention, we explored ways in which the myriad new openings required to give housing sufficient amenity could be made, without compromising the latent power of this old wall.

The task was initially one of erasure and removal. Layers of baby-blue paint were peeled away to reveal the original matte texture of its common bricks. Openings were cut to allow the awesome depth of the bonded structure to be revealed three dimensionally. Bluntly detailed concrete lintels brace the structure and hold intact the powerful scale that was jeopardized by the repetitive neediness of the tight housing modules. Metal grilles baldly screen the balconies, and fuse the individual scale into an expression of the original structural bays.

The way that detail is deployed in each urban project is specific and unique. In each project, we search for the appropriate point along the axis between regularity and strangeness, craft and trade, romanticism and realism that define the way each architectural situation inflects the evolving face of the city.

1. Quoted in Günther Vogt et al., Miniature and Panorama: Vogt Landscape Architects Projects 2000-06 (Zurich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2006), 529. Origin of the translation is not noted.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 25 Mar 2013

Words:

Laura Harding

Images:

Laura Harding

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2013