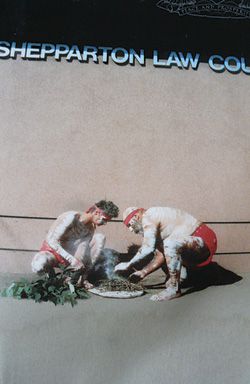

The smoking ceremony to launch the Shepparton Koori Court in 2002, as requested by local Aboriginal people.

Training around the oval bar table at Shepparton Law Courts.

The Koori courtroom showing the first donated painting hanging above the witness box.

The bench of the Nadju–Norseman Community Court is unchanged (shown here before the community table). However, donated Aboriginal paintings and photographs now hang above it.

Norseman community members, with panellist Adrian Schultz (far left) and Legal Aid lawyer Miriam Kelly (far right) around the bar table made from local timber, with an Aboriginal painting as its centrepiece.

The oval bar court table at Kalgoorlie also has Aboriginal artwork as its centrepiece.

Training within the Kalgoorlie courtroom.

Kate Auty reflects on processes aimed at increasing levels of inclusion and access for the Aboriginal community.

Notwithstanding scandalously high levels of Aboriginal arrests and imprisonment in Australia, it has taken two centuries of colonization for Aboriginal people to find a real, participatory place in the courts. Initiatives for a dialogue productive of change have come from judicial officers, Aboriginal community members and justice departments committing to attentive consultation and respectful collaboration.

Courtrooms across the country are now working towards greater levels of inclusion and access for Aboriginal people in Koori, Nunga, Murri, Aboriginal circle and Aboriginal community court processes. I have described the process in these new courts as a “sentencing conversation”.

These efforts are as diverse as the communities they seek to serve. Some are formal, others organic; some are supported by legislation, others not; some have been able to access funding while others have struggled to squeeze financial commitments out of bureaucracies. Yet every court attempts to be more inclusive, welcoming and respectful and to address the high rates of imprisonment and offending in the Aboriginal community.

This essay discusses courts where I have worked as a magistrate: in Yorta Yorta country (Shepparton, Victoria) and in Gubrin, Nadju and Wongatha country (the south, central and north goldfields around Kalgoorlie, Western Australia).

Yorta Yorta

In 2002 senior Yorta Yorta man Uncle Wally Taylor and his son launched the Shepparton Koori Court with a smoking ceremony conducted at the request of local Aboriginal people. The smoking, accompanied by dance and music, commenced on the High Street pedestrian pavement and wound its way through the courtrooms and court building.

This ceremony was part of a progression in justice. Earlier, in May 2000, the Melbourne Magistrates’ Court had incorporated Aboriginal cultural practices in a state-wide Sorry Day apology and commitment to reconciliation. The focal point of that ceremonial sitting was a welcome to country by Aunty Joy Wandin Murphy, a Wurundjeri elder. Aunty Joy’s welcome, delivered from the elevated judicial bench, was the first of its kind in Australia.

These two ceremonies illustrate how quickly, physically and culturally, we have moved from the traditional elevated bench to the surrounds or precinct – from the streetscape to the floor of the courtroom – in response to the dialogue about justice issues with Aboriginal people.

The Shepparton Koori Court was the first of its kind in Victoria. The development process involved lengthy consultation and discussion about legal processes, court etiquette and courtroom design. The court is a legal process, so much time was spent on training parties, cultural awareness training and developing what has come to be described as “the model”. Much less time was spent considering the courtroom, its design or its functional or cultural utility.

Briefly, the legal process is as follows. An accused indicates a plea of guilty and the case is listed in the Koori Court, which sits fortnightly as part of the ordinary court calendar. On the day of the hearing, two elders and/or respected persons enter the courtroom with the magistrate from the judicial officers’ corridor and they sit flanking the magistrate at the bar table. Their attendance is organized according to a roster designed by a Koori Court Worker (a court officer). The accused attends with lawyer, family members and other support people. Everyone sits at the bar table. The police read out the allegations and provide the court with any prior court history, the lawyer talks about the offending, family members and the accused may and often do speak. People may also speak from the court floor, where they are seated in the public gallery. Victims may attend and speak (organized through the police prosecutor) and victims have a seat at the bar table if they wish. The elders and respected persons speak directly to the accused and his or her family. Community corrections personnel provide reports and make recommendations. The magistrate discusses the sentencing possibilities with those at the sitting. Then the magistrate decides the sentence and imposes it. The sentencing options are the same as for the mainstream court and are governed by the Sentencing Act.

In Shepparton it was always understood that the Koori Court would occupy the third, small courtroom in the court complex. Some early discussion raised the possibility of the court sitting in the local Aboriginal cooperative building. This proposal was not, for many reasons, a practical option and it was decided that it would be better to have local senior Aboriginal people reoccupy (recolonize) justice spaces.

The court complex did not undergo any structural changes to accommodate the new court process. Entry points, to both the court complex and the courtroom, remained the same and the mainstream registry counter continued to serve as a “processing” point. Funding was available for refitting the courtroom but not for anything else. The courtroom itself had no natural light, a single entry point for judicial officers from a corridor that led to chambers, and no dock or in-custody prisoner movement capacity. The room was poorly fitted out and, being infrequently used, looked like a storeroom. It was square, with a low ceiling and a slightly elevated bench. It was clear that, once refitted, the courtroom would have to serve as both a Koori Court and a mainstream courtroom.

In a short and very informal consultation between myself, my senior clerk and some local, self-selected Aboriginal people, it was decided that the room would be refitted with a ground-level bench, a clerk’s desk and a witness box. We had to retain a bench for ordinary court processes but were determined that it would remain as unobtrusive as possible in the confined space. We considered positioning the bench in the corner of the room, but this was not feasible given the one entry point for the judiciary. It was decided that the new furnishings would be in light wood.

The single real innovation was the commissioning of an oval bar table. The size and shape of the room would not accommodate the original suggestion of a circular table, and a rectangular table was unsuitable as it was intended that all parties would sit at the bar table for all the hearings, which required easy movement around the table and the room. The oval table, built in light wood, provides for computer and microphone points, and is used for Koori Court and mainstream court hearings. Its shape fitted the needs of the court and was aesthetically pleasing.

There have been other design innovations since the Koori Court commenced. The local police prosecutor has contributed a painting. Aboriginal artwork has replaced the state’s coat of arms. One example illustrates the importance of this small design innovation. As a magistrate I dealt with a youth in Shepparton Koori Children’s Court. He and others were enrolled in some remedial secondary education, which encouraged them in art. This youth and his friends offered to paint a picture for the court. I accepted on the basis that the painting would only ever be on loan to the court and they could exhibit it whenever they wished to. I also offered to have the painting properly framed. Some weeks later I drove to court and on rounding the corner to the front entrance was alarmed to see a group of about a dozen youths at the front door, early – before the court opened. My immediate thought was that there must have been a riot the night before and they were at the court to meet some charges. Upon entering the court my stereotypical assumption was exploded. The youths were there to present the painting. This was done. They did all the talking, unusual in itself. I had the painting framed and sent out a message to the community, through the Koori Court Worker, that this had been done. A steady trickle of boys came through the court to view their work displayed on the wall of the courtroom. On one occasion I came into the court to find the youth I dealt with there with his mother. He was showing her the parts of the painting which he had painted. In Aboriginal fashion it included hand stencils and fauna; it was in ochres and “the colours” (red, black and yellow). The youth held his hand over his hand stencil and pointed out to his mother the work of the others. The youth and his mother found the courtroom a non-threatening place which had some meaning for them, they attended without being compelled to. Their conversation did not stop when I entered the courtroom but continued and included me, the magistrate. That painting, clearly a work of Aboriginal people, remains on the wall of the Shepparton Koori Court. It sits above the witness box. As the courtroom continues to be used by non-Aboriginal people in litigation and in the mainstream court, all those who pass through the court effectively sit under the hand of Aboriginal youth. That’s a powerful, but in this case non-confrontational, message. We need more of them.

Apart from those changes the court precinct and the actual courtroom remain unchanged. Non-Aboriginal people have the use of this courtroom on days when the Koori Court is not sitting, although, of course, it was Koori money that funded the refurbishment.

Nadju, Gubrin and Wongatha

Aboriginal Community Courts have also been established in Norseman and Kalgoorlie. In spite of the astounding numbers of Aboriginal people processed in magistrates’ courts, court staff and service providers (with rare exceptions) had little knowledge of local Aboriginal histories and connections. An old man told Commissioner Patrick Dodson during the consultations for the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody that “it might not be justice but it sure is quick”. These courts attempt to re-educate the administrators and also take the time to do things better. This would not be possible without some small but significant changes in the design of the courtrooms.

The Nadju–Norseman Community Court, the first we established, initially had no money spent on interior changes. The photographs show a dark brick interior focused on the pre-eminence of the bench. The photographs to the side of the coat of arms, of the Nadju dance group at the Commonwealth Games and of a group of local Aboriginal people in the courtroom, were donated. The paintings above the bench have been donated. No changes could be made to the design of the courtroom itself and entry and exit points remain the same. The Community Court has simply dispensed with the use of the bench, for both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people (if they elect to have their guilty plea dealt with in this way).

Ultimately the Department of Justice provided funding for a bar table to be made to community specifications. Rectangular and made out of local timber, it was constructed by a local Aboriginal group and has an Aboriginal painting as its centrepiece. The idea of the table came from the community representatives who are part of the court.

Gubrin Wongatha

The Kalgoorlie Community Court also operates out of a courtroom that continues to be used for mainstream court business. It is a small room but it has wonderful natural light, in spite of the fact that it faces due west, which can be a problem late on a December/January day.

The bench remains in situ, as moving it would have been costly. This bench is an ugly 1970s construction, a little raised and in dark wood, so it still has an impact on community court processes. Entering the courtroom around this edifice presents some problems for senior Aboriginal people with hip problems, but this has been addressed by ensuring that the senior Aboriginal men and women precede the magistrate into the room at their own pace. There is no dock and no provision for those who may be in custody in this courtroom.

Although this was our second community court in the region (Nadju–Norseman being first) this court was the first provided with a new bar table, at the suggestion of the Aboriginal Justice Officer, who sourced the cabinetmaker. Here, the table is oval and it also has Aboriginal artwork as its centrepiece. Indicative of the entrenched polarization in the community, a non-Aboriginal female justice of the peace, upon sitting at the bar table for a JP meeting, observed that the artwork should be “50–50 them and us”. These sort of comments are eroded on a daily basis by the simple existence of the bar table and its artwork. The design is explained in a plaque, which has also been hung on the wall of the court. In this courtroom other Aboriginal iconography is also displayed – a spear, woomera and boomerang hang above the flags. These were gifted to the court when it was launched. A senior Wongatha man explained the method of making the weapons at the time. No adverse comment has been made about the display of these artefacts in the courtroom. A painting by a local Aboriginal man who has been through the court is also hung on the wall. During hearings participants can be observed scrutinizing these changes. In the mainstream court Aboriginal people never appear to study their surroundings, they simply enter, sit, stand and leave.

To reduce the impact of the elevated and ugly bench during community court hearings, the bar table is rotated 90 degrees so that the accused and his or her family face a wall of ensigns – the Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and Australian flags – rather than the dreary iconography of control and domination, the bench.

Meetings with the senior Aboriginal people who are rostered to sit with the magistrate are held in the staff tearoom before and after the court hearings and this has exposed the court staff to Aboriginal people in social settings. This sort of interaction never happened before the Kalgoorlie Community Court started. It is ironic that the very lack of space in the present court building has contributed to better understanding across cultures. We class this as one of the unintended consequences of both the new court processes and the design features of the old court building.

Summary These innovative courts have done a lot to build respect, to create a common language and break down tensions between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. This has been done by hard work and organizational change but it has also been affected by changes, and paradoxically continuities, in the design of the courtrooms.

The courts continue to operate out of courtrooms. This provides security for lawyers and judicial officers wedded to structure. However, it also provides opportunities for Aboriginal people to enter the space authoritatively and have their contributions respected.

The ensigns of Australia, the Aboriginal people (“the colours”) and Torres Strait people provide the symbolism of state but also radically and delicately destabilize it. The abandonment of the coat of arms has occurred without comment.

The emblem of the Aboriginal Sentencing Courts appears to have become the oval table at which all parties sit. This innovation was in fact serendipitous. Our first table, at Shepparton, was crafted as an oval due to space constraints and incidentally because it was aesthetically pleasing, not because it was understood to be potentially inclusive and engaging. The Kalgoorlie Community Court has an oval table made by local Aboriginal people, of local timber and with artwork inset in the centre. By way of contradistinction, the rectangle at Norseman permits people to take up places, at the end, which appear to command some sort of authority.

The oval bar table is being adopted in mediation spaces, in newly developed Aboriginal Sentencing Courts and at the Victorian Neighbourhood Justice Centre. While it is initially unsettling for judicial officers to sit at the table and at the same level as all the participants in the cases which come into these courts, the oval is an extremely inclusive, one might even argue warm, shape.

It is possible to erode and decode dominant paradigms. Aboriginal Sentencing Courts appear to be telling us something about how we do and have done justice in cross-cultural contexts and they clearly show us how we can do justice better. The design, redesign and retrofitting of these spaces comprise a quietly insistent, highly visual part of this process.

Kate Auty is the Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability Victoria. She would like to acknowledge Professor Graham Brawn, who started her thinking about the importance of design in the courts, and Aboriginal Court Officers Daniel Briggs, Bradley Mitchell and Bev Burns and all the Aboriginal panellists who have participated in the courts.