Sean Godsell is an architect of the old school. He draws by hand, details via sketch and supervises on site, in person. An avid reader and skilled writer, he feeds the lessons of history into his buildings and deplores contemporary design as uniform and unintelligent. “My strongest asset,” says Godsell, “is my training in the history of architecture.” Unsurprisingly, developers do not figure highly in his client list.

This unrepentant non-conformism, although celebrated by the international intelligentsia, has tended to cast Godsell as a cult figure. Especially within the diehard postmodernism and try-hard eccentricity of Melbourne, Godsell’s ultra-principled stance has long seemed eccentric to the point of anachronism. Until now. Now, at last, that very staunchness is gaining recognition as a promising key to an increasingly uncertain future.

A stroll through Godsell’s oeuvre reveals several enduring themes and motifs – the box-on-legs, the lift-up flap, the shade skin, the parasol, the divided plan, the quirky tower. At first glance, such iteration suggests a degree of formalism – adherence to a look, a style or a guru. It is tempting to see the elegant plans as Miesian, to discern a touch of Murcutt or Leplastrier in the screened verandahs and the simple lift-up flaps, to liken the Vatican Chapel to Casey Brown’s so-similar Permanent Camping at Mudgee. But that would be to misunderstand.

Godsell has never heard of Permanent Camping, he met Murcutt for the first time only recently and “doesn’t even own a book on Mies.” What’s really going on with Godsell is both more personal and more interesting: a body of work that has evolved over decades from first principles and very much on its own terms.

Because of this, perhaps, the themes and motifs are all interrelated, both spatially and – having evolved, one from the other – over time. The box-on-legs is Godsell’s signature parti. In half a dozen houses over 20 years the box parti has reappeared so often that, to the naked eye, the works might blend into one another.

But this box, being glass, requires shading. This brings the external skin into play, being a combination of rusted or timber filigree screen and lift-up window flap. In turn, the double skin creates space that easily broadens into the unprogrammed space of the verandah, common territory between the colonial house, with its spinal corridor, and the Japanese divided plan (where the verandah doubles as exo-circulation). The parasol, sometimes solid with flaps and sometimes filigree, is the shade skin tipped horizontal, while the tower is the box-form stood on end.

Abstract, disciplined and minimalist to the point of austerity, the work appears to sit within International Style modernism. But this is a modernism warmed and complicated by externalities – a modernism pulled apart and “recomposed,” as Godsell puts it, in a way that enables acute response to context, culture, climate and client.

“I wanted a counter-position,” he explains. “I wanted to achieve all these things in something so scary to architects as a box.” Scary? I can see that a box may be scary to its denizens, but to its architect? “It’s dangerous ground,” Godsell explains, “because if you stuff it up, you’ve just got a boring box. It’s terrifying out there.”

In truth, there’s nothing boring about Godsell’s boxes. Ruthless in their integrity, they are lifted by that very drama, by their quality of light and their richness of thought, to a kind of sweetness.

Godsell’s work, like his conversation, is peppered with references to Japanese architecture – the endlessly renewed Ise Shrine as well as the work of Ando and Isozaki and the writings of Tanizaki. Almost every one of his buildings combines a love of rudimentary Australian shacks, sheds and materials with an admiration for the Japanese “divided” plan. This abiding interest may be in part inherited, since Sean’s father, David Godsell, was a successful Melbourne architect in the Wrightian tradition. But it’s less a formal influence than a source of themes, strategies and ideas, generating an East-meets-West take on planning and form-making that melds our colonial history with our location, as part of Asia.

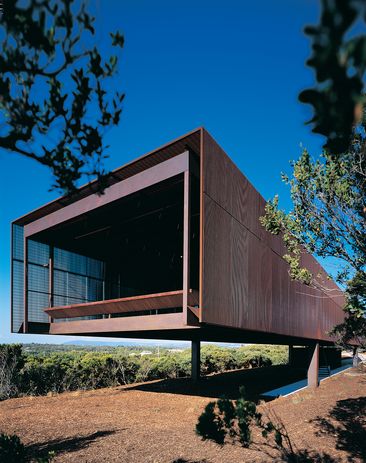

And so to the works. For many of us, the name Sean Godsell conjures his Kew House (1996– 97), a cantilevered eighteen-by-nine-metre shoebox whose sublimely simple plan is dappled by light through a fine steel filigree the colour of the central desert. Built for his own family, it was a brilliant experiment that cemented Godsell’s name in our collective imagination and contained most of the idea-seeds that have flowered in the work of subsequent decades.

Kew House by Sean Godsell Architects.

Image: Earl Carter

Kew House is divided longitudinally, on its east-west axis. The long, north- facing half is devoted to living, the southern half to sleeping. The glass is shaded, at least partially, by the finely gridded shutters that form the external skin. There’s no explicit verandah (although in a sense the whole house is a verandah) but also no corridor. The box’s eastern end is dominated by a seven-metre-long kitchen table – the vernacular family altar, what Godsell calls “the hub of life.” Now, 25 years later, he believes even more strongly that Australian informality means “all houses should have an arrival point at the kitchen table.”1

Even before Kew House, clues to Godsell’s future design obsessions can be discerned. The P Gandolfo House (Melbourne, 1993–94) topped a two-storeyed portal-frame box with a roof of exaggerated simplicity whose beams protrude to suggest infinite extension. The MacSween House (1995) has similar beams but a roof that echoes both the Ise Shrine and Godsell’s own Future Shack (1985–2001).

After the Kew House, though, came a series of riffs on the low-slung steel- screened box: the Peninsula House (2000–02), the St Andrews Beach House (2003–06), the Glenburn House (2004–07), the Edward Street House (2008–12) and the Tanderra House (2005–12) are all versions of this particular dreaming.

St Andrews Beach House by Sean Godsell Architects

Image: Earl Carter

Further evolutions occur in the House on the Coast (2014–17) – which, for the first time, bends the long box into an L-shaped plan and screens it in vertical timber; the House in the Hills (2015–18); and the giant parasols that shaded Godsell’s entry to the Sydney Modern Project design competition (2015). These immense pergolas, sailing above their pavilions, bring to mind Jun’ichir ō Tanizaki’s famous line: “In making for ourselves a place to live, we first spread a parasol to throw a shadow on the earth, and in the pale light of the shadow we put together a house.”2

The vertical, upended box has fewer iterations – the MacSween House, the timber-screened Carter/Tucker House (1998–2000), Future Shack, and the Kew Studio (2009–13), built as an adjunct to Godsell’s own house. One of the most charming is the Vatican Chapel, designed for the 2018 Venice Biennale.

Vatican Chapel at the Venice Architecture Biennale by Sean Godsell Architects, 2018.

Image: Brett Boardman

Godsell was one of 10 architects commissioned by the Holy See to mark its first-ever foray into the biennale. The brief required a chapel of no more than 60 square metres and furnished by no more than an altar and a lectern. Curated by Francesco Dal Co and based on Gunnar Asplund’s lovely Woodland Cemetery chapel, the chapels were i ntended as mobile structures that would travel around earthquake-ruined parishes. In the event, they have become so beloved as to remain on the Venetian island of San Giorgio Maggiore.

Godsell, brought up in the Jesuit tradition and charmed by the belltowers of Venice, drew inspiration from his 30-year-old ideas for Future Shack. Basing the design loosely on the 40-foot shipping container, he stood the form vertically to accommodate bells. Light enters through an oculus at the top, in reference to the Pantheon, and the interior is a brilliant gold. Godsell’s bells, having exceeded the brief, never eventuated but he hopes that, in future, they might.

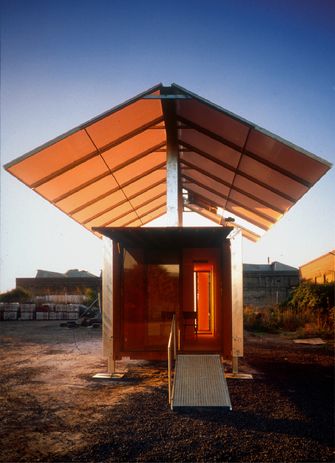

Future Shack itself was designed in 1985 but not documented until 1995 or constructed as a prototype until 2001 – “when I had some money.” An early exponent of the current container house fad, it carries some of the formal ideas (the horizontal steel box, the parasol roof) found in later works but also has serious social purpose as a mass-producible, secure and mobile dwelling for emergency and relief situations. Stylish as well as conscience-driven, Future Shack received much publicity and was exhibited for six months at the Cooper Hewitt museum in New York. But Godsell says he could not find anyone to take it on as a serous proposition and declares himself “not interested in setting up a manufacturing business.”

Future Shack by Sean Godsell Architects

Image: Earl Carter

Other philanthropic projects for what Godsell calls “compassionate infrastructure” have met a similar fate. Park Bench House (2002), Bus Shelter House (2003–04) and Picnic Table House (2009) derive from his years living in London’s Notting Hill. Noticing that street furniture in general was designed to make sleeping impossible, he shaped these objects deliberately to offer uninterrupted horizontality and a measure of protection. It’s ironic that this should amount to what Godsell calls “poking the bear.”

“I was a stirrer back then,” he chuckles, recalling the disdain with which his entry of Park Bench House into the Institute housing awards was treated. Perhaps what should give us more pause for thought is why a call for kindness is seen as provocative, even disruptive, and unworthy of design attention.

The buildings may seem almost ruthless in their purity but this, says Godsell, is simply “the artifice of architecture.” In fact, he says, it’s not a pure art. “The best forces are the extraneous ones … You need the untrained commentary to take a building out of theory and into reality.” 3 This is the role of the client. “You can’t do a good building without a good client.”

He’s no Luddite. The working drawings are produced on computer, the latest houses are fully “smart” and operable remotely via smartphone, and the RMIT Design Hub (2007–12) will one day, in its full realization, be clad in photovoltaic discs. But still, Sean Godsell realizes his ideas with an old-fashioned blue clutch pencil. When people ask what program he uses for design, he quips, “The F lead.”

This unashamed mix of futuristic imaginings and traditional methodology makes him absolutely an architect for the present; a role fully acknowledged, at last, in his richly deserved Australian Institute of Architects 2022 Gold Medal.

1. Sean Godsell, interview with Virginia Cucchi, All Good Vibes , podcast audio, December 2021, floornature.com/ allgoodvibes/sean-godsell-16772.

2. Jun’ichir ō Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows (Stony Creek: Leete’s Island Books, 1977), 17.

3. Sean Godsell, interview with Virginia Cucchi, 2021.