Photography by Shania Shegedyn

Review

View of the Customer Service Centre from the south-west, showing it in relation to the existing shire offices to the left.

The site, seen across Duke Street. The clients’ initial plan was to house overflow from the existing buildings in two relocatable “Ifco”-type huts sited on this car park.

The new elevation to Duke Street.

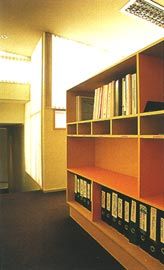

Looking along the main corridor to the link with the existing building. The simple but elegant joinery separates off the general office.

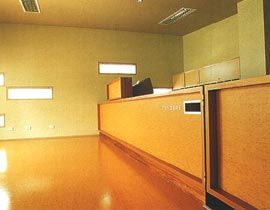

The interior of the main entry foyer, looking towards the Duke Street wall.

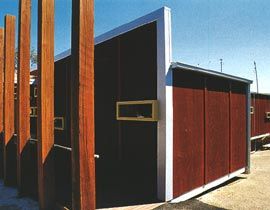

Facade detail showing the “box-like” cladding and deep reveals.

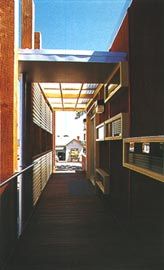

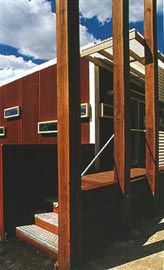

Looking along the entry verandah with its “civic” colonnade.

Oblique view of the street facade.

The south-east corner, and entry from the car park.

South-west corner and entry from Duke Street.

Contrary to predictions of endless leisure, in the postmodern era activity itself has become the location of individual fulfilment and integrity: in work we affirm our sense of self. Of course, the assessment of such work is contentious: it is validated through argument and differentiation. This makes for a condition of them and us: the knowing and the uninformed. So where does architecture reside in all of this? Is it in the site demarcated by the auteur architect, or is it in the eye of the spectator? Or is it outside any such oppositions? For the work-a-day practitioner, it is likely to reside in achieving of a level of improvement beyond what was asked for, even if this sounds simultaneously prosaic and pretentious. Indeed, if there is one cultural characteristic that crosses the architectural profession it is that we expect, above all, that the building and its context will be enriched through our application and intellect. This results in a seemingly constant opportunity for betterment. To reveal a secret vision, when all about are focused on the predictable, prescribed solution, that is the stuff of liberation and empowerment.

The story of the small additions to the Shire of Hepburn offices, at Daylesford, is a story of such a clever breakthrough. The former gold mining and spa town of Daylesford has had a recent revival as a retreat for Melbourne urbanites and for tourists from further afield. Those seeking a weekend away, a spa, a latte, a good bistro and an excellent secondhand bookshop, have been buying up cottages and busying up the main street. Towns like Daylesford remind us that the new urbanism that has changed the inner suburbs of our cities is equally transforming small towns. This is evident in the regional centres selected, seemingly at random, for a tourist bonanza. In Daylesford, the need for increased municipal offices followed the tourism boom, but the idea that this additional accommodation might parallel the new stylishness lagged, at least at first.

The project began with the shire manager’s proposal to use relocatable “Ifco”-type huts as an efficient and pragmatic solution to the need for additional office space and a customer service centre. Multiplicity, a small emerging firm lead by Tim O’Sullivan and Sioux Clark, were initially commissioned to decorate this pair of tin huts. The architects rose to the unique problem of designing bull-nosed verandahs for the sheds, seeing in it an ironic twist. But they also became interested in the logistics of the construction, transport and placement of the relocatables. The more they investigated the type, the more the idea of importing these capsules into Daylesford seemed surreal. Why not, they asked, use the constructional efficiencies of the hut, to achieve cost effectiveness, but via the skills of a local contractor? And, therefore, why not tailor the building to make more use of the site and better fit the real accommodation needs of the shire, rather than have the employees tailored to the predetermined shed?

The project shifted to a more holistic integration of building, functional resolution and streetscape design. But it is illuminating to consider that the professional skill sought originally was that of cake decoration/urban design. Those responsible for the project believed that they had the accommodation and constructional solution, but they sensed a likely controversy over sheds in the street. No need for an architect, the project was too small. But to disguise the sheds – now that was something that needed to be done!

Multiplicity’s triumph is that they worked beyond these limitations, taking the shire managers considerably further than they expected. For the community of residents and tourists, the architects’ application has produced a public asset that is of great value rather than simply expedient, that is executed with care rather than slipshod.

The building itself is modest, both in its theoretical ambition and in its formal invention. That said, it is executed with wit and sensitivity. The addition is a simple box attached to the rear of the original shire office, a proficiently designed moderne building. The new box is clad in box-like stuff – plywood and cover battens – which, within the traditions of Melbourne holiday houses, seems natural and unpremeditated. It is raised above ground, utilising the slope of the land to provide secure undercroft car parking. This gabion base gives the box an ambiguous aspect. Is it weighty and anchoring, or is it, as it appears, a stone skin infilling the piloti that elevate the main volume? The front door, facing the driveway and car park are accessed by another holiday house standard – the timber decked verandah. This element is characteristic of both the weekender and the “Ifco” hut. Its edge is marked by yet another incantation of the Denton Corker Marshall colonnade. This motif has surely become one of the signifiers of Victorian civic gravitas, and it is no less so here, even if it can be read as a parody.

Inside the building, the architects’ determination to do a better job has paid off for the users. The space is light, open and well laid out. Good control of daylight through slot windows and the use of colour and materials has created an excellent workspace which is beyond comparison with the relocatable solution that might have been.

The building is contextual in that it continues the street line. But it is also new. It is not historicist, nor derived from the “neighbourhood character” kit ordained by recent planning codes. Thankfully the disease that has infected many regional centres has been avoided here. This is further evidence of the fruitful collaboration between the architects and the shire officers, who seem to have become increasingly enlightened as the project progressed. This contextual approach is not radical. Nonetheless it has lead to an excellent result. But this is the worrying thing. Increasingly, architectural projects are less treatises or speculations, and more battles to the overcome uninformed constraints placed on the work of our best designers. Are we in times when radical action can only occur within the asylum of the exhibition? Is the controversial to be exposed only as the unbuilt loser in some ideas competition, or as a speculative pipe-dream at some global talkfest? If so, will we see less and less contact between the theoretical and the applied?

Multiplicity’s project is within a fine tradition of small municipal projects. It sustains a strong role as advocate for commissioning and encouraging designers of skill, and for allowing scope for the new. The building is not explicitly revolutionary. And unfortunately the revolutionary is no longer found at exhibitions or conferences either. It has all but disappeared, perhaps lying low in the pragmatic; keeping its head down in the struggles to get a good building built.

Ian McDougall is a principal of ARM

Project Credits

Shire of Hepburn Customer Service Centre

Architect Multiplicity—project team Tim O’Sullivan (architect), Sioux Clark (interior designer), Kim Roberts (graduate architect). Structural Engineer T.D. & C. Builder Stevens Construction. Client Shire of Hepburn.