Earlier this year, the parlous state of housing in the remote Aboriginal settlement of Santa Teresa led part of the community to a threat of legal action against the Northern Territory Government.1 Santa Teresa is just one example of a widespread and persistent crisis in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander housing, beset by problems of both quality and supply. The quality of Aboriginal housing is a design problem, although shifting political imperatives and uneven procurement strategies frequently marginalize the contribution of architects. In contrast to nationally embarrassing reports of failure, a small group of practitioners and researchers has made a significant and noteworthy contribution to identifying particular problems and testing solutions for remote Aboriginal housing for the last fifty years. The accumulated knowledge and expertise and the resulting design work needs to be more broadly shared with the profession and policymakers.

Paul Memmott outlined the intractable political and architectural problems associated with remote and regional housing for Aboriginal people in this journal in 1988 and again in 2004.2 Research literature also partly covers this ground, although climate change, predicted thermal stresses and energy poverty add to the challenge of building healthy, cost-effective and culturally supportive housing in remote areas. We might add to this list the neglect of housing in major metropolitan areas, where 35 percent of the Indigenous population resides.

In the early 1970s, architects used the RAIA to galvanize a nascent interest in Aboriginal housing, initiating a community of practice with an enduring legacy. Through a combination of research and experimentation, architects with experience in the field drew attention to the necessity of informed consultation, construction detailing and specification for health, and the importance of the delivery process. In Memmott’s book Take 2: Housing Design in Indigenous Australia, a number of these practitioners describe their overlapping approaches. In examples of carefully considered housing, the plans reveal a programmatic response to Aboriginal social and cultural domestic practices. Such informed departures from convention – or mainstream social housing type – can significantly improve the social and cultural lives of the occupants.

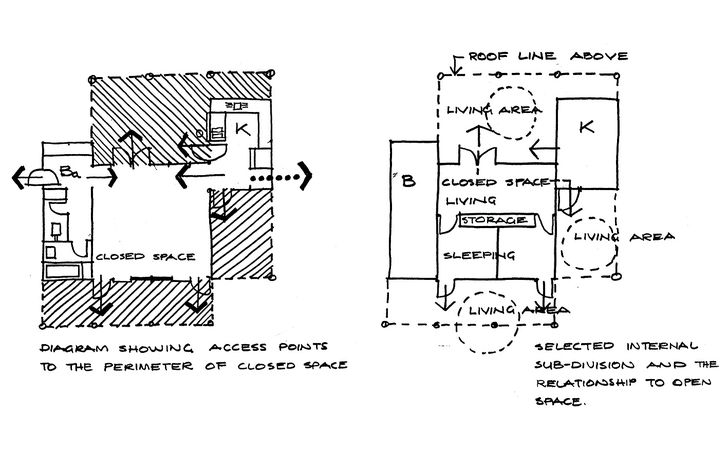

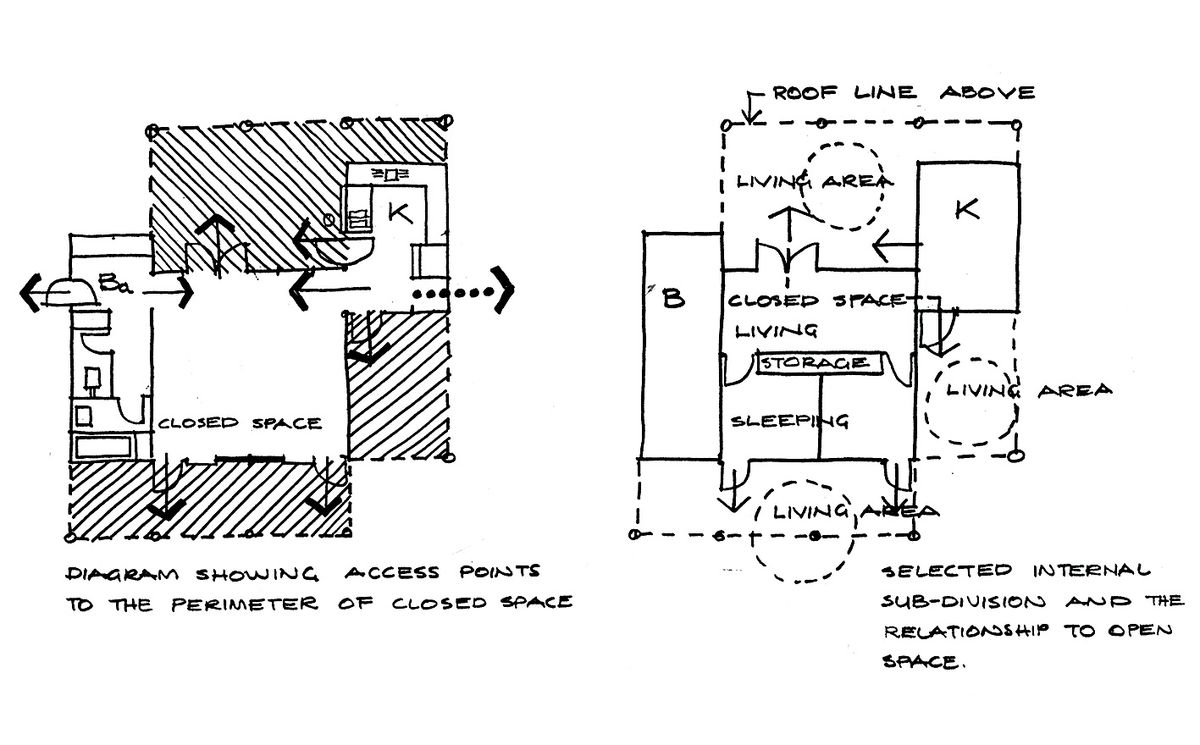

Julian Wigley’s planning ideas for the Mount Nancy Town Camp houses in Alice Springs, drawn in 1978.

The published evidence of Indigenous housing projects is meagre. In the few available sources (including unpublished reports), numerous projects illustrate how careful, skilled practice has produced culturally responsive plans for Aboriginal housing delivered within exacting environments and delivery regimes. What appear to be quotidian material and servicing decisions often mask the complexities of construction programs and the extent of accumulated knowledge specific to places and communities. The architectural moves may appear modest, but the improvement on mainstream social housing is worthy of national recognition and sharing with a broader international audience. (This architectural nous has application in other parts of the world, as Paul Pholeros demonstrated.)

Alice Springs-based Tangentyere Design has made an enduring contribution to Aboriginal housing and its practitioners and practice have influenced the field since its inception in the late 1970s. The practice, the foundations of which were laid by Julian Wigley and Walter Dobkins, has designed a portfolio of houses based on perceptive consultation, project evaluation and incremental knowledge. Despite Tangentyere Design’s reputation, director Andrew Broffman describes the difficulty in providing even basic consultation under recent funding and procurement regimes.3 Thorough consultation is hampered by remoteness and cost as well as the urgency to meet the chronic shortfall in housing reflected in the high rates of Aboriginal homelessness and crowded households.4 Without discounting the value gained from consultation and attention to place, can a broader distribution of successful precedents be used to improve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander housing?

Cultural and social practices vary considerably across the continent and certain preferences can be conspicuous in remote areas. In the Great Victorian Desert, Iredale Pedersen Hook’s (IPH) designs for community housing in Tjuntjuntjara were informed by extensive experience and thorough consultation, with a team that included an anthropologist. The plans describe a variety of spaces for living around the house, with relatively large covered spaces that can be occupied seasonally and extend shelter to transient visitors.5 Culturally responsive architecture recognizes the preference for outdoor living and use of external spaces that are still a consistent pattern in many parts of the country.6 External shelters and landscape treatments can be very useful for outdoor activities but covered areas designed into the plan are more likely to escape an expenditure review. In suburban Kununurra, IPH integrated the carport into the plan as a tactic to provide flexible outdoor social spaces that permit surveillance of the street.7

Across the country, a variety of intensely held spiritual beliefs and culturally derived avoidance behaviours present particular architectural challenges. Shaneen Fantin has documented these effects on housing in Arnhem Land, and Troppo Architects, among others, has adjusted planning in an attempt to reduce incidences of stress. Earlier this year, Kieran Wong described the cultural influences on Coda’s design for a recently completed super clinic in Karratha. Although it is not specifically an Aboriginal medical service, awareness of avoidance behaviour influenced the planning of the entry and circulation. In this case, previously arcane knowledge about culture has moved through the profession, from Aboriginal housing to a mainstream healthcare building.

After fifty years, Aboriginal housing is still in crisis and there is clearly a role for architects to play. And while there is no adequate substitute for the types of processes advocated by practitioners such as Geoff Barker and Broffman, a more consistent public record of well-informed housing designs could serve the profession well. The schemes need an explication of the design intentions, situated within a context of place, people and policy, and, ideally, different forms of evaluation. In the information age, politicized funding agencies seeking new ideas tend toward a cyclical history of forgetting. Knowledge developed through experienced practice and tested solutions is, at least, an antidote to the oft- repeated mistakes in Aboriginal housing.

1. Shuba Krishnan and Katherine Gregory, “Anger over Northern Territory Aboriginal living conditions sparks legal action, inquiry call,” The ABC website, 10 February 2016, abc.net.au/news/2016-02-10/anger-over-nt-town-camps-sparks-legal-action/7157888.

2. Paul Memmott, “Aboriginal housing: The state of the art (or the non-state of the art),” Architecture Australia, vol 77 no 4, June 1988, 34–47 and Paul Memmott, “Aboriginal housing: Has the state of the art improved?” Architecture Australia, vol 93 no 1, Jan/Feb 2004, 46–48.

3. Andrew Broffman, “The Building Story: Architecture and Inclusive Design in Remote Aboriginal Australian Communities,” The Design Journal, vol 18 issue 1, 2015, 107–134.

4. North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency, “Northern Territory Housing Issues Paper and Response to the Housing Strategy Consultation Draft,” February 2011.

5. Narelle Yabuka, “Tjuntjuntjara Housing,” Architecture Australia, vol 96 no 3, May/June 2007, 70–77.

6. Paul Memmott, “Remote prototypes,” Architecture Australia, vol 90 no 3, May/June 2001, 60–65.

7. Adrian Iredale, “Kununurra Transitional Housing,” Architecture Australia, vol 105 no 1, Jan/Feb 2016, 69–73.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 1 Feb 2017

Words:

Timothy O’Rourke

Images:

Courtesy of Iredale Pedersen Hook

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2016