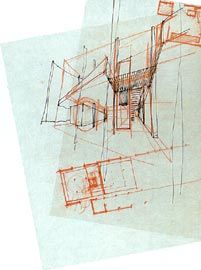

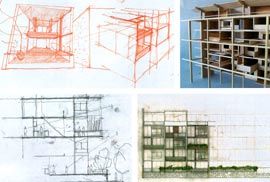

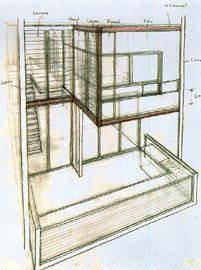

Sketches by Shelley Penn for Pier 2/3 Walsh Bay.

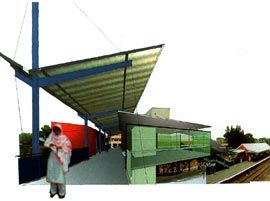

Montage of the Lakemba Railway Station.

Development work for the Garden Apartments Sketches by Shelley Penn.

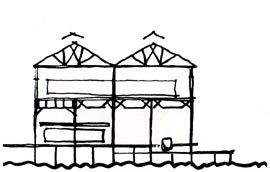

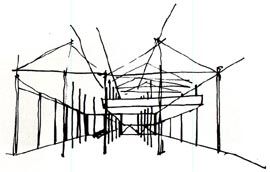

Drawings by Ben Hewett and Peter Poulet, developing the ideas initiated by Penn.

The Government Architect’s office, within the NSW Department of Public Works and Services, is a curious animal. Politically driven, and politically accountable, the DPWS – in both its role and the structure necessary to support that role – is quite unlike most successful “design-driven” architectural practices, which often represent autocracies, or, at the very least, benevolent dictatorships. The political constraints under which the DPWS operates (often required to control external influences beyond the immediate context of the architectural project) increase the already difficult task of producing architecture of consequence.

With the appointment of Chris Johnson as Government Architect in 1996, the DPWS looked set to change. Johnson has retained a real enthusiasm for his profession, underpinned by an infectious curiosity that sees his interests switch between the benefits of web-based project delivery, the nature of 19th century urbanism, the impact of mandalas on the planning and structure of Indian cities, and more. In addition, Johnson came to DPWS with a strong sense of the gravitas of his role, and of the lineage of NSW Government Architects before him. He seemed intent on raising the profile of both the position and the department to its previous highs.

Johnson’s most obvious strategy for transforming the architectural output of the DPWS was the creation of the new position of “design director” within the Government Architect’s Design Directorate (GADD) – his own “department-within-a-department”. A rotational appointment, the design director was seen as an opportunity to regularly inject the department with new input from some of Australia’s finest practitioners, raising the bar within the department while exposing private practitioners to the political, social and strategic machinations necessary for the procurement of public buildings.

The first design director came in the form of the double-headed team of Lindsay and Kerry Clare. Their appointment coincided with the commencement of a number of pre-Olympic projects, promising a focused period with clear results in a short time. The Clares effectively closed their Sunshine Coast office to move to Sydney, quickly establishing something of an “office-within-an-office” at the GADD, perhaps inevitably so given their long partnership and finely tuned collaboration. The Clares also bought a particular momentum and focus to DPWS as the inaugural holders of the role and in their open use of the appointment as a vehicle to shift from their domestic Queensland practice to a larger-scale mode of operation within Sydney.

In mid-2000, Johnson appointed Melbourne architect Shelley Penn as the second design director. Penn came to Sydney having run her own practice for a decade and having established a well-earned profile and professional respect through both her teaching and a series of beautifully considered residential alterations and additions.

Penn’s appointment came as a surprise to some, who had anticipated a change in direction for the GADD after the Clares, who had also cut their teeth on small-scale projects. Penn was younger, had run a smaller practice, and had limited experience on public buildings.

That Johnson’s first two design directors have come from domestic practice indicates the paucity of young architects with recognised experience in the public realm. The contribution of younger practitioners within large practices is often invisible.

Consequently, professional recognition of younger architects remains the domain of the sole practitioner, and it is to these practices that Johnson has turned. This pattern is of some concern, suggesting little depth within the commercial practices working in the public realm.

Penn arrived to a DPWS unsettled by the exclusivity with which the Clares had operated and suspicious of a “little known” Melburnian (in the best tradition of the Melbourne-Sydney axis, news of Penn had hardly travelled north of the border). The momentum provided by new projects that had greeted the Clares had also evaporated, and there was little in the office to kick-start Penn’s involvement. These issues, along with Johnson’s intention of modifying the role to suit the strengths of his new incumbent, ensured Penn’s tenure as design director would take a different form to that of her predecessors.

Despite the scale of Penn’s previous work, her architectural drive stems from a sophisticated, philosophical level of enquiry into the nature of society and the potential of architecture to impact upon and improve the human condition. Penn moved to Sydney disillusioned by the relentless demands of a small practice focused on high-quality work and questioning the contribution of the small project to society and culture as a whole.

The timing of the GADD appointment was perfect, providing an opportunity to investigate what it is to work within the public realm and to reflect on this experience while considering her future.

Penn focused on an exploration of processes and the potential for improving the quality of design from within the DPWS machine, becoming involved in the design and implementation of office structures that may, in some way, inform the modus operandi of the office. This exploration was, again, driven by Penn’s strong social sensibility, and focused on existing DPWS processes and their potential to draw the best out of the substantial human resource within the department, leading to a stronger collaborative sensibility focused on the production of better buildings. Penn hoped to “transform the view (within the DPWS) about the role”, repositioning the design director as a facilitator, focused on the dialogue between private practice and government.

It will be no surprise to those who have experienced both forms of practice that Penn, like the Clares, found the adjustment from small practitioner to government operative problematic. Penn is a serious architect who practices in the hope of making a positive difference to the lives of those who occupy her buildings, regardless of scale.

This seriousness brings with it a level of intensity that does not always sit comfortably within a government’s architecture office. While Penn’s reputation is based on an oeuvre of residential work under $500,000, a DPWS graduate may be given a $2 million school to design and document: the mindset, effort, quality expectations, constraints, demands and process between the two models varies enormously.

This intensity has meant, for Penn, an economy and focus in her work where every line, every presentation, is an exploration focused on realising a built work. However, in government, Cabinet directives and ministerial pressures can result in the need to design and present projects “immediately” for political purposes. Johnson excels in this role, switching between twin guises – both a consultant to government and the director of a business. Beyond Johnson’s skill at handling these demands, he genuinely seems to enjoy the “lightness of touch” that comes with having to attend two cabinet meetings, an Olympics briefing and to design a train station by lunchtime. For Penn, this did not make sense as a method for making fine architecture given her previous experiences working within a tightly controlled, highly focused practice environment.

With Penn’s departure in the middle of this year to give birth to her son, Harry, another transformation in the role has taken place with the appointment of Peter Poulet.

Poulet has been promoted from within the department. This is an important move. It recognises that considerable talent exists within the DPWS itself and that this talent can (and should) be instrumental in making better buildings. Poulet, who has worked closely with both previous design directors, may also take a critical role in liaising between them and the department. Johnson hopes to continue the dialogue he commenced with the Clares and Shelley Penn, gradually building a family of people and ideas around the GADD that will ensure its central place within architecture in NSW for some time to come.

Gerard Reinmuth is a director of Reinmuth Blythe Balmforth: Terroir

Shelley Penn is a thoughtful, poetic architect, with a fundamental concern for how people inhabit space and how they use a building in a contextual sense. The role that Shelley played as design director was twofold. She was involved as a project architect on projects including Lakemba Railway Station and Pier 2/3 Walsh Bay. Most of her work, however, was with others in the office – either in a design review role or as part of a team. This included investigative work with MVRDV on “Port Cities”, the Flexible Component Design Range for the NSW Department of Health, competitions for Reconciliation Place and Ultimo Pool, the “Garden Apartments” concept, and the Government Architect Pattern Book. A source of a great number of our conversations within the office in regard to these projects was the consideration of, and compassion for, the human experience in relation to architecture. When working with people in the office Shelley encouraged them to push themselves further, while supporting them – allowing them space to maintain a confidence with their work.

The “Garden Apartments” concept is one of a number of initiatives that Chris Johnson set up in response to the Premier’s call to raise the quality of apartment design. It takes the idea of large areas of outdoor living, normally associated with detached housing, and appropriates it for apartments. We spent some time exploring the idea, and investigating the repercussions of large outdoor living spaces off the ground. The elegant simplicity of Shelley’s ideas meant that finding an order to our investigation was very straightforward. The clear articulation of these ideas has ensured the intention has easily carried through into our ongoing work with garden apartments.

The open-minded, ordered and critical approach Shelley brings to her work is also evident in feasibility work done for Pier 2/3 Walsh Bay. Strong ideas of defining existing and new as discrete elements enable the integrity of the existing structure to be read.

The new is also expressed with its own language, thereby complementing the existing.

To a large degree Shelley redefined the role of design director. Her willingness to make the role work as support to not only the Government Architect, but also to DPWS architects, meant a lower profile as “design architect”. However, it also meant that Shelley’s role within the department was far reaching, as her critical skills could be brought to more work and more people. Understandably, this was a difficult role for someone used to running their own practice, but it brought a unique perspective to the office, helping to foster a confidence in our approach to our work within the constraints of a large government office. Shelley stood for design excellence, and was an inspiration to all of us.

Ben Hewett is a design architect with the Government Architect Design Directorate, NSW Department of Public Works and Services in which Peter Poulet is the new design director. He worked with Shelley Penn during her period as design director and with L