The exterior of the new Online Training Centre at Victoria University’s St Albans campus, by Lyons Architects, is an architectural enigma. From the road several hundred metres away at the southern edge of the campus, the building seems to appear out of, and merge into, the foreground field of dry grasses and prickly growth (the habitat of the striped legless lizard). The building’s most dramatic effect at this distance is the arrangement of window openings – seen as graphic black slashes across the hazy surface. As you drive on, skirting the field, these slashes partly dissolve and the golden blur resolves itself into a giant diagonal net of vibrant yellow and duller browns. At this middle distance the whole building appears swathed in plaid.

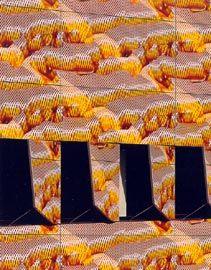

The building then disappears from view, reemerging when the nondescript campus has been negotiated. Closer up, the building is even more graphic. From the adjacent car park the facade reads as a panelled surface printed with a complex pattern. But as you cross the last few metres on foot, the overall pattern recedes and the peculiar qualities of the individual panels take over the visual experience. Each is a virtual landscape covered with a grid of distorted dots. These dots appear like perforations in a threedimensional surface that, close up, seems to bulge and swell and recede.

The creation of changing experiences at various distances, registers and scales was one of the architects’ key intentions. It has led to a richly allusive project. Many ways of thinking about surface and decoration are pulled into play by the ambiguous skin, and the multiple apprehensions it generates invite proliferating speculations and interpretations on the part of the viewer.

The distant view brings camouflage to mind: skin (maybe striped legless lizard skin) mimicking environment. Each facade responds to its immediate context, both visually and physically. (In contrast to the facades visible from the road, the one directly facing the predominantly monochrome campus is a more sober grey.) Seen from a distance the building does not assert its identity by standing out from its environment – its appearance comes from a more dispersed condition. Viewed more closely, however, the figuring on three sides exceeds any attempt at camouflage. It is too flamboyant to merge or hide and other interpretations come to the fore. For example, the mid-distance impression of a woven pattern might recall, for some, the proposition of nineteenth century theorist Gottfried Semper that the surfaces which enclose buildings originate in textiles and carpets, in technologies of the knot. Closer still, the shifting pattern invites speculations about visual perception. Each glance seems to reveal different forms, which, when gazed at intently, seem to ripple and pulsate before the eyes. This undecidability makes the viewer concentrate, and she or he becomes aware of seeing and looking as physical, volitional activities.

Moving around the building, visual experiences continue to expand

and intensify.

The angled, hooded openings on the east and west faces play more perceptual tricks.

Made from the same patterned cladding, the collective form of these trapezoidal hoods suggests a kind of rent in the building’s skin that has puckered or pleated. The southern facade has no shades, but it “stretches” around the windows, suggesting yet another manipulation of the building envelope. A bed of stones – another kind of landscape representation – surrounds the building. Seen obliquely, the colours and shapes of the patterned faces seem to mirror, one-to-one, these stones.

The building interior is, of necessity, mostly a black box, but the dramatic fenestration and the perforations suggested by the external patterning imply a general condition of permeability. The different treatments and scale effects of the extraordinary exterior relate to the architects’ interest in the skin as a permeable mediator between exterior and interior, between landscape and internal function and program.

The building skin has been constructed, conceptually, from a melding of the two. The custom image applied to the Vitrepanel surface is a digitised representation of some kind of imaginary, bizarrely animate, perforated landscape. Oddly smooth yet deeply riven, it is quite unlike the surrounding flats of Melbourne’s outer west.

This image reflects, in part, the operations possible in Photoshop and 3D Max. Computer technology is often heralded as a way to create “new” architectural forms, previously unthought of shapes and spaces that, in extreme versions, might be designed to move, to be literally animated. The architects of the Online Training Centre have used such technology to do something simpler and possibly more interesting. They have not fetishised the techniques; rather they have used them to generate an appearance for the building that raises broader questions about architecture. In particular, these are questions about architecture’s audience, about the constituencies that architecture addresses. These questions move us well beyond the particular encounter of any specific fascinated individual.

For one audience – that steeped in architecture’s own culture – the building could be seen in connection to Semper, but also, and perhaps more compellingly, to a Melbourne architectural tradition of decorated surfaces. On the one hand, through the city’s Victorian heritage, this tradition relates to John Ruskin and his contention that architecture lies in the surface of “decorated construction”. On the other hand, it relates to Robert Venturi and to billboard facadism. Both these possibilities might prompt an architectural audience to consider its relationship and its responsibility to various other audiences.

Ruskin and Venturi would both reject the equation of architecture with fine building craft, for such architecture addresses other architects only. This solipsism equates with irrelevance. Who is it, then, that architecture should address? There is no easy answer. In arguing that architecture was decorated construction, Ruskin contended that the excess of labour, design, and materials that this entails constituted a kind of sacrifice, a prayer, an offering to values higher than those of human utility or even human understanding. Venturi’s pop architecture sought to engage architecture in some way with popular taste.

Lyons’ Online Training Centre does not quite follow the paradigms of either Ruskin or Venturi: there are no higher values for us to appeal to, and populism alone now seems cynical. But, in the haze and visual undecidability of Lyons’ St Albans facades, perhaps some remnants of both these lost ideals also hover. Just occasionally they come into focus if you look carefully enough: a reminder that architecture might be more than well-wrought building.

Credits

- Project

- Online Training Centre, Building 10, Victoria University, St Albans Campus

- Architect

- Lyons Architecture

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Neil Appleton, Geoff Cosier, Chris Georgiou, Gillian Moody, Andrew Lilleyman, Carey Lyon, Cameron Lyon, Natalie Stanborough

- Consultants

-

Building certifier

Peter Luzinat and Partners

Quantity surveyor Wilde and Woollard

Services engineer Bassett Kuttner Collins, C. R. Knights

Structural engineer Arup

- Site Details

-

Location

St Albans,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Mar 2002

Words:

Paul Walker,

Justine Clark

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2002