A TINY PROJECT ON THE EDGE OF THE GIBSON DESERT, THE PATJARR VISITOR CENTRE HAS BIG AMBITIONS TO CONSTRUCT LINKS WITHIN AND BETWEEN COMMUNITIES.

The Patjarr Visitor Centre as airstrip gallery. Photograph Matt Rumbelow.

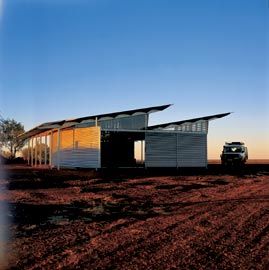

South elevation.

North elevation.

East elevation. Photographs Oli Scholz.

Students and staff prefabricated much of the building in the university workshops.

Students and staff prefabricated much of the building in the university workshops.

Students and staff prefabricated much of the building in the university workshops.

Students and staff prefabricated much of the building in the university workshops.

Students and staff prefabricated much of the building in the university workshops.

Erection of the visitor centre on-site at Patjarr.

Erection of the visitor centre on-site at Patjarr.

Erection of the visitor centre on-site at Patjarr.

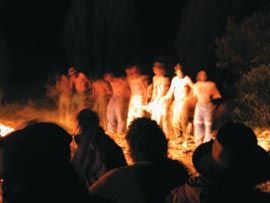

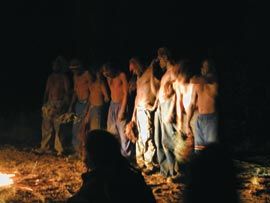

The handover of the building, including emu dancing. Photographs Oli Scholz.

The handover of the building, including emu dancing. Photographs Oli Scholz.

The handover of the building, including emu dancing. Photographs Oli Scholz.

The campsite adjacent to the visitor centre, demonstrating the students’ familiarity with the fine grain of the land.

The campsite adjacent to the visitor centre, demonstrating the students’ familiarity with the fine grain of the land.

The campsite adjacent to the visitor centre, demonstrating the students’ familiarity with the fine grain of the land.

The completed building in its vast context. Photographs Paul Pholeros.

The completed building in its vast context. Photographs Paul Pholeros.

The completed building in its vast context. Photographs Paul Pholeros.

The completed building in its vast context. Photographs Paul Pholeros.

The visitor centre’s southern opening. Photograph Oli Scholz.

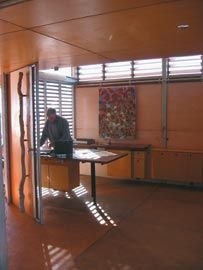

Gallery space displaying works from the Patjarr Community and other surrounding Aboriginal communities.

View from the interior gallery space back towards the entry. Photographs Paul Pholeros.

THE APPROACH TO this small building involves two-and-a-half hours of wonder.

Heading near-due-west from Alice Springs by light aircraft, you first fly along the West Macdonald Ranges, then across salt lakes with grey/white fluid patterns and tributaries – the oldest rivers on earth cutting through ranges that used to be higher than the Himalayas, now weathered to a mere few hundred metres in height. Green bands of saltbush and mulga show five seasons of high rainfall and recent water flow patterns.

Finally dune country, a fluid sand mass with ridges strictly conforming to prevailing wind patterns.

After flying nearly 1,000 kilometres, it is only during the last three minutes of the journey that you see the gravel landing strip and the finished Patjarr Visitor Centre building on the edge of the Patjarr Aboriginal Community,Western Australia.

It takes time, then, to travel to the Patjarr Visitor Centre. Our group travelled by two light aircraft and one was delayed by strong headwinds. To reduce load the food was abandoned en route. The first team to arrive went to the community store and bought a night’s emergency supplies. Temporary landing lights were placed out along the airstrip and the second plane touched down at very, very last light. Visitors arriving by road may have an even more intimate, if less obviously dramatic, two-day introduction to the region. Many of our group have made numerous slower and more eventful road journeys to Patjarr during the four-year span of this project.

I was invited to Patjarr as the guest of a small group made up of students and lecturers from the University of South Australia, a Sydney-based journalist, a doctor and a pilot.We were to see the recently completed visitor centre handed over to the Patjarr Aboriginal Community. The building has been the collective effort of around 130 architecture and design students and staff from the University of South Australia and the University of New South Wales over four years. The project involved two years of design and the prefabrication and assembly of components in Adelaide and Sydney.

Then an on-site building team of over twenty students and four staff substantially completed the building in three weeks during June 2002. Subsequent visits by the two university teams completed building details and internal furniture and fittings. Much of the $80,000 cost of the building’s materials and transportation came from a Western Australian Lotteries grant.

This building could be the world’s first fly-in art gallery. Designed to display and sell the works of the Patjarr Aboriginal Community (and other surrounding communities), the “airstrip gallery” cleverly exploits the fact that Patjarr is a key re-fuelling stop for flights from the centre to the west of the country. For the light-plane pilots there is a navigation chart table, flight planning and rest area adjoining the gallery area.

Other associated projects, such as the dance ground with seating and protected areas, and various community improvements in Warburton Community (south of Patjarr), were also designed and constructed by the group. These associated projects, while not as photogenic as the visitor centre, have a grit of community engagement that is not often seen as the work of the architectural profession. The student camp, nestled into a small valley within metres of the visitor centre, has the look and feel of an old, lived in, armchair – well sited, modest and functional. Remnants of less “architectural” interventions have been reused and adapted.

The group’s use of the camp demonstrates a familiarity and confidence with the place. Unfamiliar eyes often miss the fine grain present within this vast and arid landscape – knowledge of it comes through time spent living with the country, not through lectures and facts. The students’ small campfires and quiet conversation show that they have noticed and appreciated this finer grain.

All of this building activity is located a few hundred metres from the Patjarr Aboriginal Community. So what has the connection between these two communities been like? As with most Indigenous communities, interactions of substance involve apparent chaos. While I was there, students voiced their disappointment that community members were not more involved in the building process. However, the speed and prefabricated nature of the construction would have precluded almost any external involvement. This is something to ponder for the next project and design process – is it better to involve more local people in a building that is less crafted and prescribed or can the two be brought together in other ways?

Nonetheless, the various journeys to the site have built up good links with the local community and, as the process of organizing the handover of the building got underway, old friends appeared and disappeared without fuss or formality. Various other activities, everyday and otherwise, were also in process at Patjarr, including a meeting involving regional Ngaanyatjarra Council representatives. All in all, then, this was an average community day, with an architectural opening placed well and truly in the larger community perspective which the building will inhabit over time.

And then the art started to arrive. In great quantities! With an organizational ease that only Aboriginal people can muster, meetings ended, visiting senior Aboriginal people were invited to join the festivities, kangaroo tails were cooked and dancing organized.

Sunset brought together kids, dogs, fire, roo tails, emu dancing and the formal handing over of the key – from the Patjarr design group to the chair of the regional Ngaanyatjarra Council, it was then passed to senior traditional land owners, the community chair and, finally, to those responsible for running the centre.

But this is an architecture magazine, not a travel one, and the question will be asked, “Is it a good building?”Well, it is carefully designed and sited, extraordinarily well crafted with thousands of hours of love and care put into the fabric. On the three days of the visit it was well attended by planes and community people, so its brief seems to have been fulfilled.

This small building also raises bigger questions and issues, both architectural and pedagogical. Despite the students’ appreciation of the grain of the landscape and the community, this building, its material and construction, is not immediately part of this place – in the same way, the charter planes or Toyotas, and the visitors they bring to the Patjarr Visitor Centre, are not. But as planes, vehicles and even visitors have to adapt to the desert to survive and function, the test of this building and the process that made it will be how it can be adapted and how it is used by the Patjarr Community and visitors.

Most opinions about the building and project as a whole, however, will be based on photographs. It will be the images of the remote centre that will return to the edges of Australia. The photo “shoot” seemed continuous. Composing and fine-tuning images involved moving people, swags and bedding and capturing the precise light angles and intensity. Thousands of photos were taken of the building in every conceivable light and angle by cameras ranging from the expensive Swiss to the disposable Australian. Some of these images are sure to surround these words.

But, just as no wide-angle lens can capture the landscape in which this project was conceived and made, so any thoughts on the architecture of the centre must be framed more broadly.We must look not simply at the building as object, but also at the many other connections that have been built. The project has begun to construct the foundations of a meeting place between Aboriginal community people and the design team; it has established a framework for interaction between large organizations such as universities, small Indigenous communities, and the architectural profession; it has built strong relationships between students and staff and between student themselves.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the Patjarr Visitor Centre project has built a connection between all those involved and one of the great unmade places of the country.

A lot of building for such a small and beautiful shed. Thanks to all those involved.

PAUL PHOLEROS IS AN ARCHITECT WITH MUCH EXPERIENCE WORKING IN AUSTRALIA’S UNMADE PLACES.