I like to find something in-between. Not only [between] nature and architecture, but also [between] inside and outside. Every kind of definition has an in-between space. Especially if the definitions are two opposites, then the in-between space is more rich. – Sou Fujimoto

It is a very Japanese trait to distil complex ideas into a simple statement or metaphor. What is left unsaid is often more meaningful than the simple concept itself. Toyo Ito and many other Japanese architects exemplify this. Sou Fujimoto is one such example and yet he has pushed this conceptual basis and amplified the dichotomy, perhaps allowing for even further understanding or [mis]understanding, as the case may be. He starts with a series of very simple binary oppositions: nature versus architecture, inside versus outside, complexity versus simplicity, and then pushes those oppositions to the extreme – just short of parody – where they become almost absurd. Then, he makes them work.

Encased in glass yet hidden within a secret garden, the project plays with different layers of boundaries.

Image: Iwan Baan

This extreme of opposition is made clear in Fujimoto’s Toilet in Ichihara, Japan (2013), which explores the conflict between public and private, openness and enclosure. A simple toilet cubicle, constructed entirely from steel-framed glass, is placed in a garden. The garden has then been enclosed by a high timber fence and one lockable gate. The project is confronting: one is placed “on show,” as a private activity becomes almost performative. Yet at the same time the security of the locked gate allows for a moment of solitude, reflection and a chance to relax in the garden free from disturbances. There is a subtle humour here that is present in all of Fujimoto’s projects. The success of the project had tourists queuing up to snap photos and ironically forced the local government to install portaloos nearby to keep up with demand.

Fujimoto was in Australia in July as a guest of the C+A Talks presented by Cement Concrete and Aggregates Australia (CCAA) – a fine series of annual talks presented by some of the best international architects. Though only at the beginning of his career, Fujimoto is already receiving world attention. The clarity of his approach, his obvious intelligence and ease of disposition belie his forty-two years, yet what is perhaps most surprising for someone so young is the strength of his projects. By establishing simple binary oppositions as the starting point for his designs, he allows his testing ground to be the space in-between, the place of complexity. The “smooth” and “striated” are notions the French philosophers Deluze and Guattari discussed in their treatise Mille Plateaux. The point of complexity only exists between these two extremes and they only exist in combination, such as haptic versus optic.

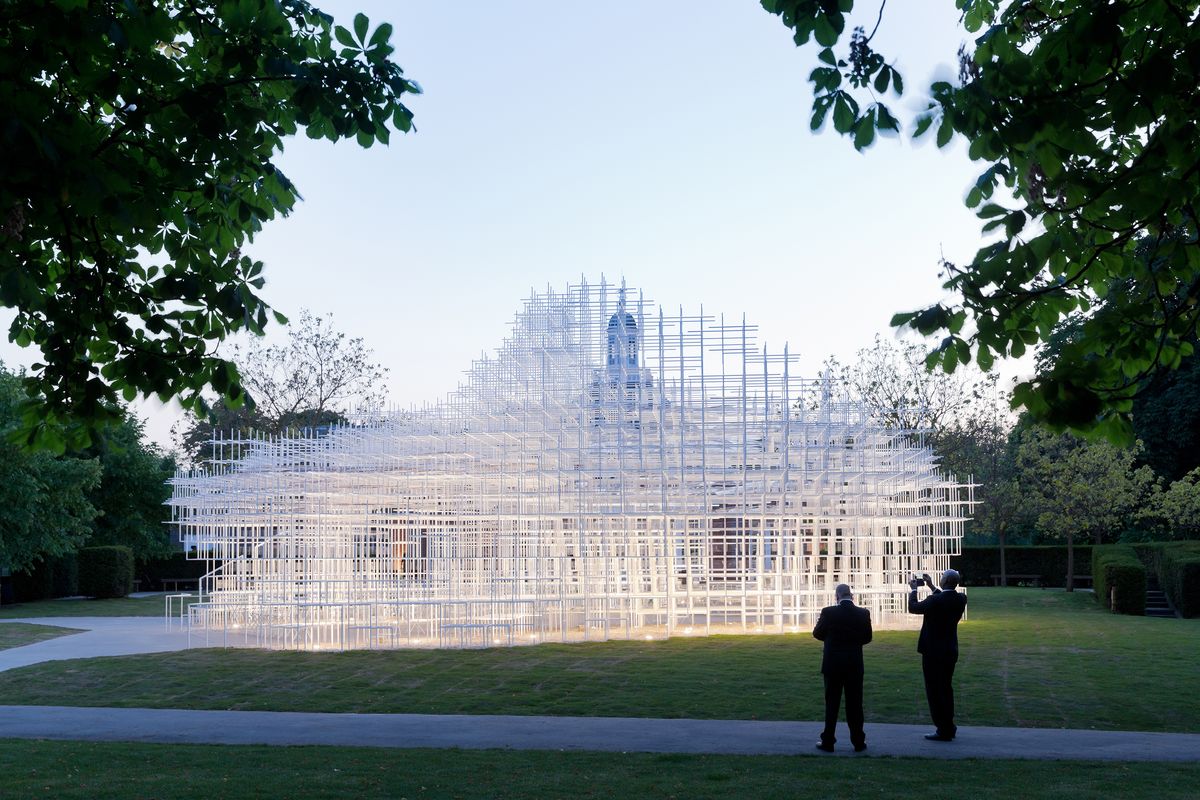

The pavilion’s delicate, grid-like structure allowed its edges to blur against the landscape and Serpentine Gallery building.

Image: Iwan Baan

In 2013, Fujimoto became the youngest ever architect to be chosen to design the prestigious Serpentine Pavilion in London’s Kensington Gardens. In this wonderfully bucolic setting, his design focused on the artificial, embracing the grid in all its white, modernist purity. By multiplying and layering the same 400mm grid, Fujimoto amplified its reading, transforming it into a haze. The lack of any program requirement in the project brief meant that there was no need for the usual pragmatic accompaniments such as doors or windows. The project moved beyond mere folly through the deft employment of simple transparent polycarbonate discs to form shelter from the rain, and the careful placement of acrylic terraces to define space, platform and seating: the bare essentials of a social space. He edits the grid as much as he adds to it. He describes it as “half grid and half soft-blur. The experience is half nature (like a tree branch) and half super-artificial things.” Together, these opposites formed a soft cloud that hovered in the park and played sublimely against the verdant landscape and the classical Serpentine Gallery itself.

White Tree (L’Arbre Blanc) by Sou Fujimoto Architects, Nicolas Laisné Associés and Manal Rachdi Oxo Architects.

Image: Courtesy Sou Fujimoto Architects, Nicolas Laisné Associés and Manal Rachdi Oxo Architects

The last and perhaps most impressive project presented at the talk was the successful entry to the Architectural Folie of the Twenty-first Century competition in Montpellier, 2014. In White Tree (L’Arbre Blanc), Fujimoto and his collaborators Nicolas Laisné Associés and Manal Rachdi Oxo Architects took the cantilevered balcony and arrayed it unrelentingly across an entire building. The common terrace space of the holiday tourist city becomes the facade, the form of the building and its defining attribute, as though nothing else exists. This simple move at once creates ambiguity of form while also blurring the traditional boundaries between inside and out, a gesture so rarely seen in apartment buildings. The form is beguiling and yet more than just form. Like the Serpentine Pavilion, Fujimoto’s determination to make the project work resolves issues of privacy, identity and practicality to create a wonderful addition to the Montpellier skyline.

In these projects we are no doubt seeing only the beginnings of a long and productive career in architecture, as Fujimoto is already receiving commissions for larger and more ambitious works. I for one look forward to following his career and asking, as with so many of the best Japanese architects, how does he make it look so simple?