Architect Conrad Johnston’s new home in the Sydney suburb of Balmain is a confident synthesis of old and new that looks back and forward in time. The house is one of a pair of semis originally built in 1972 on a steep waterfront site on the Parramatta River, facing south to Iron Cove and west to Birkenhead Point. When the two residences were built, the site was owned by architect and sculptor Marr Grounds and his father Sir Roy Grounds (1905–1981), whose built legacy includes the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne and Wrest Point Casino in Hobart.

It’s believed that Marr commissioned Stuart Whitelaw, a tutor at the University of Sydney where Marr also taught architecture, to design and oversee construction of the semis (No. 6 and No. 8). Marr had occupied semi No. 6 while Sir Roy used No. 8 (the semi now owned by Conrad and his wife) as his Sydney pied-à-terre.

SRG House by Fox Johnston.

Image: Brett Boardman

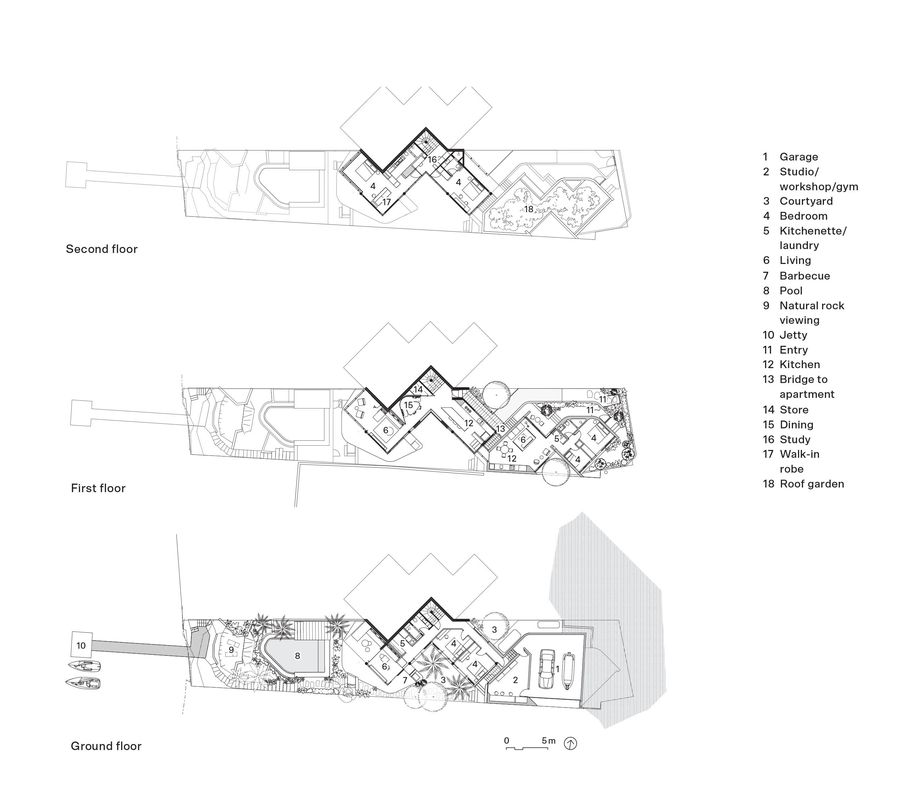

To traverse the narrow site, the semis were built at a 45-degree angle to the street, zig-zagging around large coral trees and sandstone outcrops to cleverly gain harbour views to the north from No. 8, which faces south. Its concrete pillar and slab construction was infilled with timber-framed floor-to-ceiling glass.

While the full extent of Sir Roy’s influence here is unclear, his complex geometries are certainly at play – particularly the “circle in a square” spiral staircase in the rear corner. The house changed ownership in the mid-1980s following Sir Roy’s death, and alterations included the addition of a single-level garage to the street frontage and enclosure of the first-floor living room balcony.

Conrad and his wife had been drawn to the location and the building’s unusual character when they bought No. 8 with a view to re-imagining it. While the structure was sound, its timber cladding and windows were rotted beyond repair and the original interiors had been plastered over. The project became an archaeological exercise.

“When we first saw the house, I didn’t know anything about its history, or that it was heritage-listed*. A real estate agent we knew rang and said, ‘I’ve got this weird two-bedroom, three-storey house that no-one wants. Do you want to have a look?’ I really loved the sense of it, the fact that it’s a small site but feels like there’s a lot of space and garden. But inside it was unlivable. Once we started stripping out the false linings, there wasn’t much left but the concrete. And after 50 years, all the services needed renewal anyway.”

An indoor–outdoor rumpus overlooking the pool was created by raising the room up to the level of the courtyard.

Image: Anson Smart

The building had other problems, too. With an uninsulated flat roof and only fixed glass to the south and west, No.8 suffered extreme heat gain in summer and loss in winter. It relied on a commercial-scale air-conditioning unit that occupied half of the ground floor.

One big move was to redevelop the single-level garage, adding a self-contained apartment above, linked internally to the main house. Its white-painted curved brick wall and roof garden have a seventies sensibility, though it is clearly distinct from the main house. “With all its glass walls, the original house is very light and transparent, whereas the brick garage and studio, buried in plants, is demonstrably earthbound,” says Conrad.

Keeping within the original 70-square-metre footprint, Conrad has turned two bedrooms into four and forged new openings into the garden. Interior linings were stripped away and the concrete shell was painstakingly restored and left exposed. New windows of high-performance glass have been made to the original grid, with sliding sections that transform virtually the entire first-floor living level into a balcony, while dramatically improving airflow.

On the ground floor, the air-conditioning system was removed and the space converted into two new bedrooms. They adjoin the cool, south-facing courtyard, sharing this level with an indoor-outdoor rumpus off the pool. On the second floor, the master and second bedrooms and bathrooms have been refitted.

The bathrooms are tiled in a red Japanese finger mosaic in a nod to the original tiles found on site.

Image: Anson Smart

Materials invoke a rich seventies palette with a contemporary edge. New cedar window frames and external timbers are a convincing match to the original mission brown. Wood-wool ceiling panels and new-generation cork flooring on the first floor are both acoustically insulating and carbon-positive. Plywood joinery with brass detailing throughout combines warmth with lustre, while claret-coloured mosaics in the bathrooms are inspired by the original red tiles unearthed during demolition.

The redesign does not just improve the environmental performance of the house considerably, it also manages to hold seemingly contradictory goals in harmony. While interventions such as the curved dining room banquette and sliding glass sections have softened the building’s rigid geometry and connected it to the landscape, the material richness of the new interior captures the tactile essence and spirit of the seventies.

* This article notes the heritage listing of the semi-detached house. The article has been changed to reflect the information stated in the New South Wales state heritage inventory, which can be viewed here.

Source

Project

Published online: 1 Apr 2021

Words:

Peter Salhani

Images:

Anson Smart,

Brett Boardman

Issue

Houses, April 2021