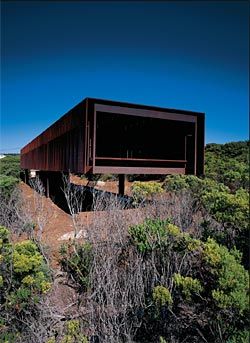

The cantilevered building appears as a telescopic form aimed at the view of the sea.

The house opens up at each end, allowing for protected verandah spaces. A large-section Corten steel profile acts as both barrier and seat or table.

Internal view of the living/dining/ cooking area, with the grid of the enveloping skin visible above.

One of the “in-the-round” bathrooms.

The more enclosed space of one of the bedrooms, looking out to the transparent walkway.

A sheltered gallery connects the stairs to the living/dining/cooking spaces and deck beyond.

Craft is a school of patience. Patience is what you acquire by working again and again on resistant materials. There is never a right or a wrong, only a closer and closer approach to the wholly useful.

Patience is the mother of joy.1

How does work grow? In increments on a line of development? Or is the business more complex, more rhizomic? While the practice of Sean Godsell Architects is by no means confined to the linear, certain works are emerging that are the product of a particular line of research. The house at St Andrews is one of these. Peter Zumthor, an architect that Sean Godsell admires, wrote recently, “The core of my work is staying at home, forgetting the world around me and submerging myself in the tasks I have to do, the atmospheres I want to create. Research, the joy of working, of finding a form for an everyday ritual, for a special moment in the future life of a building not yet known …”2 There is an uncanny parallel here with Godsell’s practice, and the craft of that practice. The St Andrews House, the latest realized work, is quite unmistakably a house by the designer of the Kew House of 1997. It is, however, even more purposeful – a telescopic form aimed at a view of the sea, which is framed in the folding of the dunes and isolated from intrusions of neighbouring houses by the barrelling form of the house. This “telescope” house is held up by, and cantilevered from, four columns, the contours of the dune flowing laterally and almost unimpeded underneath, interrupted only by a block of utility rooms that screen two-thirds of the undercroft from the road.

Sparking the image of a spaceship, a thin stair hangs from the belly of the house, touching a concrete slipway, inviting ascent to a platform that is, in effect, the lip of the telescope. This places arrival within the frame of the view, well beyond the eyepiece. Strangely, the invitation to ascend creates a sense of loss – having abandoned the road and the car that has floated you from the city to the sea, you are now to lose the shadowy space of the undercroft, forsaking its cool, fringed with foliage, for a bright and social unknown above. But, once mounted, the stairs take you up into a gallery – a space that frames the seaside and its evocations of family holidays over generations, in this place to come and in others past. After a while you discover that you are indeed in a room “with a view”, but one that is also a platform for living, dining, eating, talking. A room derived from verandahs, says the architect. A room thus affording a privileged overview that is protected from the contemplation of strangers, even though at first sight this is a house seen from all sides, like a souvenir on a mantle shelf.

The image of a telescope is not an idle one.

The house presents the same skin on all sides, like a barrel – a skin formed from a rusting steel grate.

The architect, referring to Gray’s Anatomy and to developments in surgical treatment of burns, likens this to a spray-on skin. This skin is conceived of as a cellular surface designed to protect the body (of the building) regardless of orientation. The skin attacks the problem of airconditioning, presenting a defence to insolation on all fronts, much as scales protect a fish in the round. Some parts of the grid are hinged and can be opened to the north to provide unmediated access to winter sun, though it is difficult to imagine anyone doing this, so much would it disrupt the sense of the house.

For the architect, evolving a skin that is capable of protecting buildings from the environment multi-dimensionally is a major focus for research.

In the context of global warming, he sees this as a prime frontier for architecture, a way in which buildings can be weaned off reliance on “live” energy and become modifiers of climate at the place of impact. He envisages skins that incorporate moisture collection, UV filtering, fire protection – skins that can sweat and breathe. Godsell’s design, with Peddle Thorp, for the National Portrait Gallery competition incorporated such a skin and he sees the development of such surfaces as an important area of architectural responsibility, thwarted somewhat in public projects by current notions of risk management that are driven by short-term concerns rather than what is really at stake.

The architect argues that this house extends the lineage of the Kew House: “A mature version of that concept, with a greater coherence of materials.” He had looked at the Kew House and felt that “what was wrong was the white ceiling”. This plane was at odds with the object-like quality, the “spaceship” effect that is suggested when the Kew House is viewed from the road. The plane asserts connections to a tradition of abstract planarity, which includes the Barcelona Pavilion, when the architect is more interested in Japanese temples and the frames of timber construction. At St Andrews, the cellular skin that he has been developing in other mediums (short lengths of bamboo, oblique cut, for a house in China, for example) wraps right around the house.

The elevations are made of the same material as the floor soffit, walls and roof. It is as if the house could be spun around, picked up off its four-column cradle and “handled”. And in the living area the grid is visible overhead, through layers of glass and double-skinned, cellular, polycarbon sheeting.

The plan of the St Andrews House is on a new trajectory, as if the Kew House racecourse plan has been unzipped and rearranged into a single line.

The architect calls it a “bar code” plan; a plan idea that he first used in another house (in the Yarra Valley), which, due to the exigencies of approval processes, is yet to be completed.

Backtracking from the arrival platform, a living/ dining/cooking section is accessed through either a floor-to-ceiling door or a matching giant, glazed swing wall that opens the entire area to the sea view.

Behind this, and separated by a slot open to sky and ground, are bathrooms and bedrooms reached via a walkway that is within the screen skin but is otherwise external. The bathroom is the first “in-the-round” bathroom that the architect has realized – a moment of axial perfection, dreamed of and at last accomplished. At the end is another deck, braced and protected from the drop to the ground (as is the arrival deck) by a large-section Corten steel profile that is both barrier and wide seat or table.

In the tea-tree scrub flowing up to the house, and in the line of view to the sea, is a sunken trampoline.

Sitting on the living deck, gazing out to sea, the heads of bouncing children interrupt the view. The clients are immensely happy with the house, and flushed with a sense of having been patrons to something of more than passing importance. Partly such pride is enabled by the object-like quality of the house. It is very easy to think of picking it up, holding it in your hands. This is an unusual quality, and it certainly eludes the other houses in these dunes, all of which assert a rather hubristic rootedness. But of course this “picking up” is a matter of reverie, not of actuality. More capable of sustained contemplation is the rigour of the argument that the house makes, about its siting relative to the view and the passage of sun and wind, about the way in which its skin mediates between inside and outside. Here, those who write about Godsell’s work come up against a Zen-like quality. These buildings, for the writers and clients at least, promote contemplation of our place in the universe.

Some regard such architecture as elite and arcane, removed from everyday life, and would sneer at this attempt to account for the sense of connection to the eternal that these buildings evoke, that inner peace and calm. In part, this is because, in a curious way, this architect is indeed a craftsman: he works “hands-on” and the artefactual quality of the result infects contractors with a similar enthusiasm. There is a joy intrinsic to good craft.

But I would like to appropriate Shirley Hazzard’s claim for literature and assert that architecture, and this work in particular, has a general impact on us and our culture, whether we are lucky enough to own such a house or not:

“The idea that somebody has expressed something, in a supreme way, that it can be expressed; this is, I think, an enormous feature of [architecture]. I feel people are more unhappy, in an unrealized way, for not having these things in their lives: not being able to express something or to profit from somebody else having expressed it.

It can be anything, but it’s always, if it’s supreme, an exaltation.”3

Images: Earl Carter, Hayley Franklin

1. William Bryant Logan, Oak: The Frame of Civilization. (New York W W Norton & Company, 2005): 181.

2. Peter Zumthor, The Annual Architecture Lecture: Summerworks, Royal Academy of the Arts (UK), 3 July, 2006.

3. James Campbell, “Review: Notes from a small island”, The Guardian, 8 July, 2006.

Credits

- Project

- St Andrews Beach House, Mornington Peninsula

- Architect

- Sean Godsell Architects

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Sean Godsell, Hayley Franklin

- Consultants

-

Builder

RD McGowan Building

Building surveyor Wilsmore Nelson

Interior design Sean Godsell Architects

Landscape consultant Sean Godsell Architects, Sam Cox Landscaping

Structural consultant Felicetti

- Site Details

-

Location

St Andrews Beach,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Sep 2006

Words:

Leon van Schaik

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2006