Brisbanites like me, with memories of long hours of study in the former buildings of the State Library of Queensland, can only marvel at the living institution we have in our city today. For most of the 80s, our bookish pursuits were hosted in the fustily intimate reading rooms of Centennial Hall, the late 1950s extension to the nineteenth-century building (formerly housing the state museum) by F. D. G. Stanley in William Street on the north bank of the Brisbane River. At the time, the wheels of an expansive cultural ambition were turning, and piece by piece on the south bank of the river the rambling Queensland Cultural Centre was realized. The fourth stage of the complex opened in 1988 as the new home for the State Library and for many years after, countless studious, transient folk whiled away time in the deep interiors of the straight-faced concrete and glass edifice by Robin Gibson and Partners.

In both of these earlier incarnations, the institution was contained. Information was held inside and you went inside to get at it. The State Library’s most essential function is that of a research library of legal deposit, and not that of lending. Like the Library of Congress and the British Library, the State Library has been referred to as a “library of last resort.” Its role in preserving knowledge has always been significant, and for many years its channels of obligation and responsibility were well defined. Likewise, the architectural response in both instances reinforced containment, the library separated from the world outside, carefully excluding any threat, behaviour managed, decorum enforced. While there was always constrained sociability in the after-school study sessions of teenagers, for the most part the place of study carrels, stacks and reading tables was quietly mono-functional.

In both of these earlier incarnations, the institution was contained. Information was held inside and you went inside to get at it. The State Library’s most essential function is that of a research library of legal deposit, and not that of lending. Like the Library of Congress and the British Library, the State Library has been referred to as a “library of last resort.” Its role in preserving knowledge has always been significant, and for many years its channels of obligation and responsibility were well defined. Likewise, the architectural response in both instances reinforced containment, the library separated from the world outside, carefully excluding any threat, behaviour managed, decorum enforced. While there was always constrained sociability in the after-school study sessions of teenagers, for the most part the place of study carrels, stacks and reading tables was quietly mono-functional.

In the decade following the library’s relocation to South Brisbane, the internet was delivered broadly unto the world, altering the shape of our lives in many ways, not just our libraries. In parallel there was a strange decline of public space, the sharpening chimera of the “virtual,” and the rise of privatizing just about everything. In detaching information from place, the internet had library-loving visionaries all over the world reckoning the role and relevance of libraries in the changing scene, redefining libraries as multivalent destinations, not places of last resort. Looking back from our vantage point, a tenth of the way through the twenty-first century, it is rewarding to reflect on how deftly this techno-socio-cultural revolution was interpreted at the governmental and institutional level in Queensland – in timing and in scope, and in the coalescence of people, place and policy.

In 2001, the Queensland Cabinet approved the Smart Libraries Build Smart Communities strategic policy, and committed to cultural and technological change. In the same year Lea Giles-Peters became Queensland’s third State Librarian (and the first woman in the job). She says she “walked into” this policy space, which set out the visions and values for the new library building and the entire Queensland public library system within the wider “Smart State” ideology of growth and development. Doubling the space of Robin Gibson and Partners’ original, and integrating the new whole into the larger context of the Millennium Arts Project, was the flagship undertaking of the new policy. Arguably a key lesson of the successful (and increasingly better understood) outcomes of the project was the prescient envisioning of library futures that grasped open-endedness and open-handedness like a mantra, busting the myth of perfect completion and inoculating against some kind of uptight, architectural jewel as a final product.

As the years have passed and the city has grown accustomed to its open, generous knowledge place, designed by Donovan Hill and Peddle Thorp, it becomes ever clearer that the imaginative design mission articulated between the library and its architects is fulfilled daily. The team agreed on “six spheres for contemporary library design” – that the new library should be an accessible place, a constantly transforming place, a virtual place, a voice in its place, a place of interactions, and a place with atmosphere.

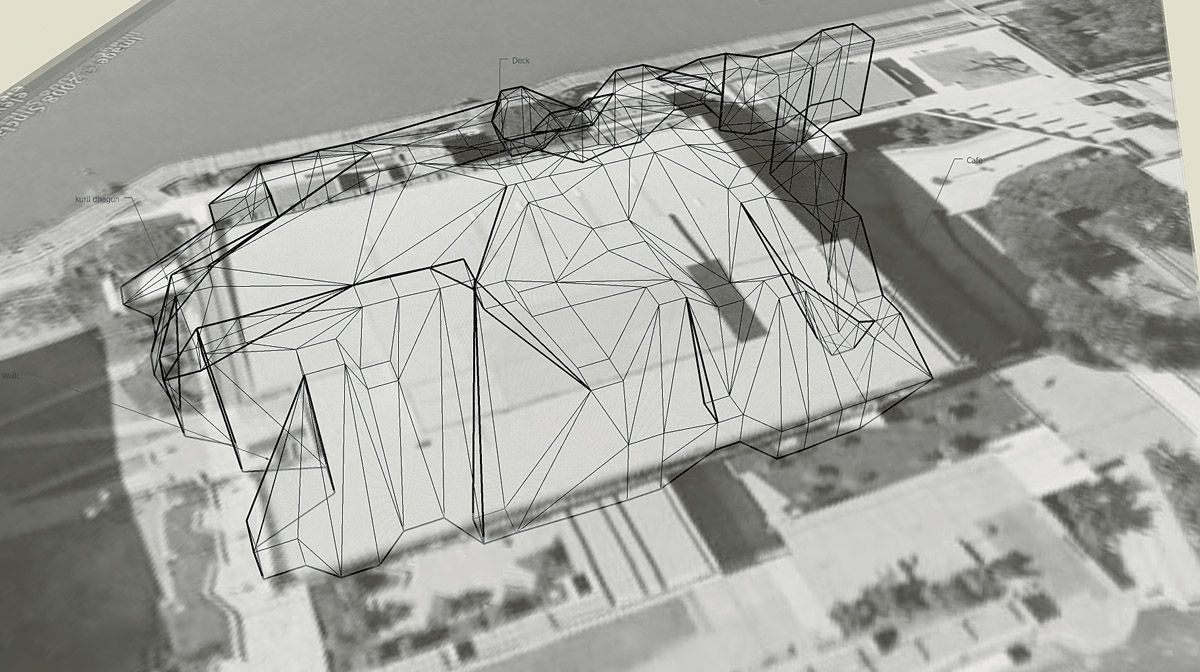

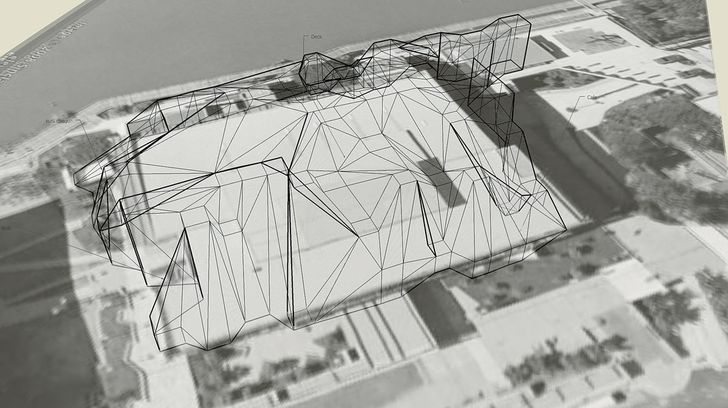

A 3D model sketch of wi-fi strength in the library. Peaks represent good signal strength. Credit: Dan Hill.

Against all of these wish notes the building resonates. Half a decade on, the sense that the reinvented library is a work in progress – a transforming place – is tangible. Organizational momentum is palpable and visible and supported by a committed coterie of volunteers. Energized, engaging and responsive, the library building and the learning culture it propagates have attracted, year by year, greater numbers of visitors. They come with an interest in the building as an architectural destination. They are drawn to the variety of public programs on offer and, not insignificantly, turn up and stay for hours for the free Wi-Fi. The State Library’s success has been consuming and only in the last reporting year have the numbers of visitors decreased. This is due to a rethink of public programs, with the goal of building a sustainable, long-term audience.

Quickly recognized by the architecture profession as a fantastic contribution to architecture and the city, in 2007 the State Library was honoured with the F. D. G. Stanley Award for Public Architecture. Readers will likely have noted already that the genuinely public nature of the building is an aspect often remarked on in reviews, helping to consolidate our contemporary understanding of what a public building could or should be (there’s a danger we were starting to forget) in our super-benign climate. Given the fuzzy interpretation of “public” in a collective consciousness so used to spending time in mostly privatized spaces, which are implicitly offered to a delimited demographic, the diversity of library patrons reveals a much broader cross-section of the population.

The range of places constituted at the library also helps us realize in our more casual age (and freed from prim and arguably irrelevant conceptions of functional type) how an intelligently suggestible ambiguity of space, form and enclosure will more often reap a reward of continuous interest and engagement. The fact that many of the really memorable places were never part of the brief to begin with, but were instead realized in the process of designing, is surely something to reflect on and from which to learn. These elemental yet complex places were cultivated as a series of ideas, imaginatively refined through role-play thinking, and supported within the project by communities of interest who believed in them: the Red Box, the Queensland Terrace, the Knowledge Walk (and the Big Table within it), the Talking Circle, the River Decks. Thanks to the open-ended, not-only-but-also nature of these key places, the range of activities that the library is now hosting is a mix of the expected and the surprising. The synergies of relationship recognized through the library’s transformative turn of thinking have seen the creation of the Asia Pacific Design Library (as a way to reinvent the reference collection, moving towards a new level of engagement with patrons already participating in other design-related programs) and the physical relocation of the Queensland Writers’ Centre from Spring Hill to level 2 of the library. The emblematic exterior/interior of the teacup-lined Queensland Terrace is a popular spot for weddings, as well as event and policy launches, workshops, pre/post-auditorium lecture receptions, and in “down time” a beautifully deep margin to hang out with your iPad.

The world-record attempt at the largest ballet class held witnessed 1,359 participants partake in a thirty-minute barre class over five levels.

Image: Leif Ekstrom

The program of the recent Ideas Festival held in and around the library and at The Edge (the newest library element, a digital culture centre for young people) included a record-breaking attempt at the world’s largest ballet class. It was originally intended to be staged on the new Kurilpa Bridge, but sudden autumn rains necessitated a change of plans, and so the Knowledge Walk and all of the galleries that look into it were marshalled, with gracious haste, to host the extraordinary event. The intimate grandeur of the generous void lined with 1,359 tutu-clad ballerinas of all ages, genders and skill levels was unforgettable. Such responsiveness banked a lot of human interest, increasing even further the citizenry’s goodwill towards the institution.

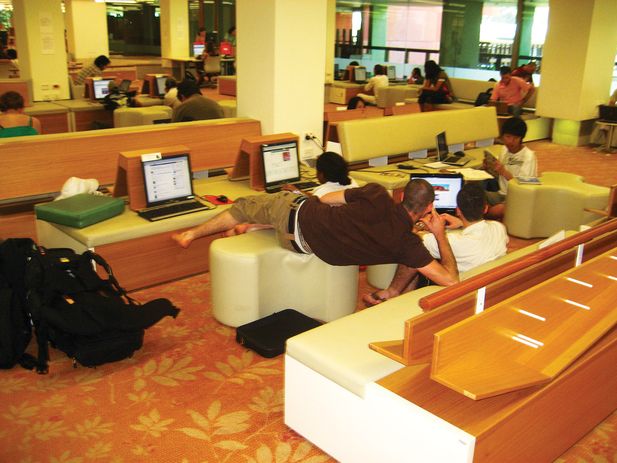

The digital dimensions of the library’s mission have inexorably fed its physical success. After writing about the library on his City of Sound blog, designer and contemporary urban chronicler Dan Hill was noticed by Tory Jones (SLQ’s Building Development and Design Director), who subsequently invited him to conduct an evaluation of the public wireless LAN service. In his capacity as Urban Informatics Leader at Arup, Dan undertook the study, which revealed the extent to which the free public Wi-Fi and the range of accessible and attractive places in and around the library mutually engage patrons. A survey revealed that three-quarters of the patrons questioned were there for the free Wi-Fi alone, but that a quarter of those went on to use another of the library’s services, such as the cafe or the bookshop. Many of those surveyed already had the internet at home, but were there because it is a nice place to “be” online. Fremantle librarian/blogger Kathryn Greenhill, discussing the concept of “radical trust” (a current topic in the field of library and information science), notes more anecdotally that backpacker hostel buses make regular stops at SLQ so that guests can keep in touch with home. Both Hill and Giles-Peters describe the charge they feel at seeing people in the Knowledge Walk very early in the morning and very late at night, nestled with their laptops, occupying and modifying the public space to their own purposes.

A related register of the impact of the institution on the public imagination is its presence in social media. While the library maintains event information streams in Facebook and Twitter and image and video streams in Flickr and YouTube, it is the content generated by patrons and visitors (the thousands of images in Flickr tagged “statelibraryofqueensland” or “SLQ,” for example) that is building the vernacular record of interest in the places and programs that the library offers.

A library user makes use of the building’s free wi-fi at the Peanut table.

Image: Tory Jones

The “bio” of SLQ’s Twitter profile (@slqld) says: “We are a large public library provided to the people of the State of Queensland, Australia, by its government.” Beneath the beneficence of this charter, the minds that made this building detailed its real potential for bounty. In her introduction to the 2011 Ideas Festival, Giles-Peters wrote, “I’ve always been fascinated by the concept of libraries acting as living laboratories; spaces where communities can learn by doing.” Everything about the library reverberates with life and learning, and there is a great deal that other organizations and institutions can learn from the SLQ experience.

In the 1987 film Wings of Desire, by Wim Wenders, there is a beautiful scene where angels Damiel and Cassiel spend time in the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin. They listen in on (“observe, collect, testify and preserve”) the very human thoughts that invisibly fill the awesome space of Hans Scharoun’s magnificent building. Each time I visit the Knowledge Walk I am reminded of that scene and the “listening in” of the architecture (and behind it, the architect) and of what a listening architecture enables, including the things which were not asked for but were heard by the architect and given a “voice.” Timothy Hill of Donovan Hill described the library project as “an act of transformation over 1000 meetings.” Now, as a real place, it continues transforming through the millions of interactions with its public, telling and retelling a story of civic benevolence, which we all implicitly understand.

Thanks to Tory Jones, Timothy Hill, Liz Watson and Jennifer Thomas for discussing their experiences of the library building. Lea Giles-Peters’ comments were taken from an unpublished interview with Margie Fraser. Dan Hill’s blog is www.cityofsound.com and Kathryn Greenhill’s site is kathryngreenhill.com and blog is librariansmatter.com/blog.

Read more on post-occupancy here.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 1 Sep 2011

Words:

Sheona Thomson

Images:

Adrian Greig,

Leif Ekstrom,

Tory Jones

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2011