Research published by the Australian federal government has found that the growing social disadvantage of people living on the urban fringe will be a significant challenge for all levels of government and policy makers. The research was released in the 2014-2015 edition of the State of Australian Cities Report on 6 July 2015, but the government has kept it under wraps since it was printed in December 2014.

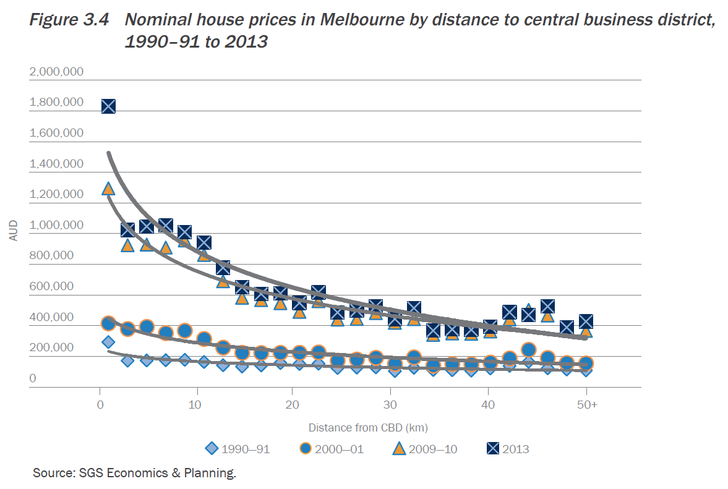

“Australia’s cities are now increasingly characterized by the significant spatial divide between areas of highly productive jobs and the areas of population based services, reflected through the price premiums associated with houses that have better access to the city centre,” the report said.

The report paints a picture of a divided Australia – between those who live in dense inner city urban areas with access to high-wage jobs and services and those living in sprawling outer urban areas who suffer from social disadvantage.

The price of housing, which has risen disproportionately according to proximity to city centres, has caused Australia’s cities to fracture along the lines of income, level of education and access to amenities, the report found.

Nominal house prices in Melbourne by distance to central business district, 1990-91 to 2013.

Image: State of Australian Cities Report 2014-2015

“In terms of the built form of cities, this price premium is having ramifications for the type of urban development that is occurring,” the report said. “Marked increases in density are occurring where price premiums are highest. This price premium is also facilitating substantial changes in the type of dwellings that are being provided.”

The price premiums in inner city areas have made housing increasingly unaffordable to low-to-middle income earners. The below map shows only 5% of nearly all metropolitan Melbourne is affordable by low-moderate income purchasers in 2006 compared to 1981. The areas that are most affordable, are well over 30 kilometres from the CBD.

Percentage of houses sold which were affordable to low-moderate income purchasers, 1981 and 2006.

Image: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute

This shows that the socially disadvantage are being pushed towards city peripheries. “The [price] differences mean residents of outer urban regions are likely to be increasingly constrained in their ability to move to inner regions,” the report said.

“There are concerns held by researchers, state governments and local councils that while land release on the urban fringe may have once been a valid strategy for boosting the supply of affordable housing, this approach may be increasingly problematic.”

The report concluded: “This outward movement of disadvantage and population is occurring concurrently with an inward concentration of higher-order jobs, placing many residents far from the opportunities of the inner city and adding considerable pressure to the increasingly strained transport network.”

Michael Buxton, professor of Environment and Planning at the School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University said, “This is a terrible story and it has grave implications for the future social harmony of our cities. It’s a serious problem that could affect the functioning of the cities for the next generation.”

Buxton warns that Australian cities risk becoming like third-world countries if something isn’t done to reverse this trend. “I can envisage in 30 years’ time, within a generation, [Australian cities are] going to be so spatially differentiated, that we’re going to have higher income areas guarded and protected by private police forces and so on. You see this in Mexico City.”

“There needs to be a radical review at all levels of government,” Buxton continues. “At the moment, the commonwealth government doesn’t want to know about this problem and doesn’t want to be involved in cities planning at all. It thinks city planning has nothing to do with it, and it couldn’t be more wrong.”

“Fundamentally, it’s going to take integrated policy across various sectors of government that are now silo-ed,” Buxton said, who believes governments should link economic and social policies with planning policies.

Buxton suggests a number of ways to tackle the spatial and social division, including increasing the level of services, such as public transport, childcare, hospitals and good education, to outer urban areas and building affordable housing in inner and middle ring suburbs. “The only way to do that is to completely change our zoning systems to have inclusionary zoning mandated so that new developments [must include] a mandated proportion of affordable housing to cater for lower income groupss,” Buxton said. “This is already happening in Australia. In Adelaide, for example, there’s a 15 percent proportion now required. In many cities in the world, it’s 20 percent.”

Australia is an intensely urbanized country and the division is set to intensify with a growing urban population. The report found that 75 percent of the population live in Australia’s largest 20 cities and 60 percent live in the largest five cities: Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and Adelaide. This is well ahead of the global average of 54 percent of the world’s population living in urban areas, according to the United Nations.

Population growth has been largely concentrated in inner city areas and the urban fringe. The report singled out Melbourne City and the Melbourne’s fringe suburb of South Morang as having the highest rates of population growth in the country, with 5,400 and 5,700 additional people, respectively, between 2011 and 2012. Metropolitan Melbourne is also the city with the highest rate of growth, adding 200 people per day, or an extra 750,000 people in the past decade.

This has had a direct influence on the built environment with significant changes in the mix of Australia’s housing stock.

“There are currently two predominant locations for population growth occurring across Australian cities: extensive low-density growth on the urban fringe and significant growth in high-density city centres,” the report concluded.

Detached housing is in decline as a proportion of all dwellings. In Sydney, semi-detached houses and apartments have increased from 35 percent of the city’s total housing stock in 2001 to 56 percent in 2011. In Melbourne, the proportion increased from 24 percent in 2001 to 41 percent in 2011. Most of the detached dwellings were built in urban fringe areas.

But this mix of housing stock is not providing people what they actually want or need. Research from the Grattan Institute, published in City Limits: Why Australia’s cities are broken and how we can fix them, found “there is a great mismatch between people’s preferences […] and the actual stock of housing.”

“A significant proportion of people want to live in a semi-detached home or an apartment in locations that are close to family or friends, to shops and to transport options,” said authors Paul Donegan and Jane-Frances Kelly. “[But] there are large shortfalls of semi-detached housing and apartments in the established areas of both Sydney and Melbourne. ”

The State of Australian Cities Report 2014-2015 also examined Australia’s economy, human capital and labour and infrastructure and transport as well as the state of some regional centres. See the full report here.