Photography by Trevor Mein

Review

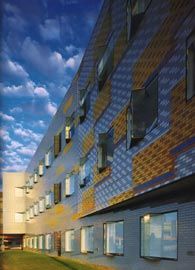

Oblique view of the animated main facade of the ward building, which enables exchange between the patients within and the world beyond. A building in a proposed later stage will connect to the curved end of the ward block, seen on the left.

Overview of the front of Sunshine Hospital, with the new ward building in the foreground.

Concept drawing.

Detail of the north elevation of the ward building.

Detail of the south elevation of the ward building.

Interior of the hydrotherapy building.

A nursing station on the ground level.

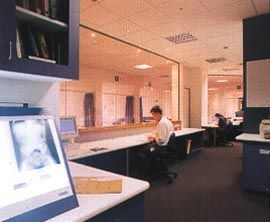

One of the shared office spaces which occupy the central zone on each level.

The “Ned Kelly” face of the new surgical theatres.

Details of the southern face of the ward building.

The eastern end of the ward building, on the left, and the hydrotherapy building, on the right. The hydrotherapy building mimics its larger neighbour in a cruder form.

South elevation of the hydrotherapy building.

South elevation of the ward building, seen across the car park.

Lyons’ recent additions to Sunshine Hospital are important because they overtly insist a hospital can be architecture, and not just a formulaic outcome of budget and function. Sunshine’s interior is humane – an efficient working environment without being reduced to the clinical; a decent place for patients and their visitors without assuming the ersatz domesticity that commonly figures in the hospital design of recent decades. Its new exterior fronts up to the diffuse public environment of Melbourne’s outer west – freeways, arterial roads, car parks – and gives something back to it. It is a success.

Sunshine, formerly a campus of the Western Hospital, was made in stages and pieces from the late 1970s. It was built to spread amorphously. The new work by Lyons includes an extension to the hospital’s suite of surgical theatres, a new building housing the hospital’s hydrotherapy facility (basically a pleasantly warm pool), and a three-storey ward block. This block is more frontally disposed, formally clear, and attuned to the wide space in front of the complex than anything already there.

Each of the new building elements presents a notable face to the exterior world. The surgical suite’s glossy walls and Ned Kelly windows, however, look to the hospital’s back yard and will probably not be seen by many. It is the remarkable south wall of the new ward block, and the hydrotherapy building – a miniature version of its ward block sibling – that make a new front for the institution to the public realm. Like other recent Lyons buildings, the effect is one of breathtaking strangeness: the buildings are puzzle pieces, inviting viewers to make of them what they will.

The first challenge is the cast of the ward block. It is faced with glazed brick, arranged in a pattern that develops across the wall surface in a pixillated pattern of grey, white, orange, yellow, and blue. The effect is certainly sunshiney. This building is a kind of billboard establishing a brand, and the change in scale that Lyons introduce with it matches the changed scale of the local context instigated by the construction of the nearby Western Ring Road freeway. But there is more here than a expansive pop gesture. The graininess of the pixel-bricks suggests that maybe there is a bigger picture, that the daubs of optimistic colour might resolve themselves into something very specific if we squint at the right distance or angle. Whether such a picture exists here or not (and not all of us ‘get’ those magic eye pictures) matters less than the invitation to the viewer to actively look. I think the building in fact only pictures itself. The upper two levels of the block begin to cantilever out at the middle, and therefore cast a shadow on the wall of the lower level. To make sure we get it, a zone of black bricks set this shadow permanently in place, as it might permanently be hatched on an architectural drawing. More black bricks make another fixed shadow on the building’s short eastern wall, under a canopy over a secondary entry.

The fenestration of this ward block wall makes another order and grain, continuous across the surface in a rhythm syncopated by the pattern of the coloured bricks. The windows within this order also invite participation, this time from within. Each window projects as a bay, with a base low enough to sit on and wide enough to serve as a generous shelf for flowers and cards. Patients, their friends and their families and the tokens of affection they exchange are clearly visible from without. This is so especially during evenings when the facade becomes a lit grid of poignantly human scenes. Inside, patients in turn can look out to the world. And they actively pursue this opportunity, apparently more than their own privacy. The views available are not beautiful in any conventional sense, but they are lively with the comings and goings of the car park in front, then Furlong Road, and the raised scimitar of the freeway beyond.

Lyons’ strategy for the ward block has been about getting address for the hospital as a whole by asserting the larger scale. Simultaneously, this has produced the maximum outlook for patients to the world beyond the institution. It’s a win-win situation. The stacking of wards on top of each other apparently goes against current attitudes in some hospital design circles that hold that big floor plates are best because they are flexible. Too bad if patients want to see the sun or anything as blandly comfortable as a car or a footpath. But these wards are apparently working well, against scepticism about removing patients with limited mobility from ground level. Success has come from care with planning at the micro scale and through developing models of nursing and care that consider the effects of this plan form. Each of the three floors of the ward building has patient rooms and facilities along the perimeters with a central service zone through the middle whose walls are strongly coloured (green, orange, blue in descending order). The colour and the timber trim are cheering, but there is no pretence in the patient spaces that this is not an institution. And all the better for it: “home” does not always live up to its reputation. Nevertheless comfort matters: where possible carpet is used, and the palliative care unit on the ground floor offers facilities not only for its terminally ill patients but also for family members who spend long hours there. A lounge and the secondary entry with its small adjacent garden are for their use.

The service zone on each floor houses bathrooms and storage areas. Offices for clinicians and nurses are also there – unconventionally shared spaces, successful because they eschew traditional professional boundaries. Nurse stations are consolidated into a few nodes with counters that generally bulge out into the corridors on either side of the service spine. This strategy, and the bend in the southern corridor on levels 1 and 2, reduces long-hospital-corridor syndrome.

A certain logic motivates Lyons’ glazed brick wall and the ward block it fronts.

Architecture here is found in accommodating the need from within for patients to connect with the world and the need from without for the institution to address the public realm, no matter how fictive the idea of the public may now seem. The puzzle of the hydrotherapy block – the other element that Lyons have disposed as part of the institution’s new front – may be harder to crack. Here’s my version. It is a reduced replica of the ward building, perhaps to be read as a model or a sketch. It is not so slickly finished as its neighbour – the bricks unglazed and in a conventional range of browns; the three-dimensional modeling of the bigger building curtailed. But though simplified, all the elements of the ward block are there as traces: diagrammed in the arrangement of different brick tones. Even the fake shadows are there.

This treatment of the hydrotherapy unit transcends function: the building is a kind of garden folly in a landscape of cars. It is an assertion in the usually utilitarian context of the hospital that utility alone does not architecture make. Nevertheless, the building works well, the small, relatively high windows giving privacy within, and so on. But Lyons main interest has been to engage the exterior in an architectural game of self-reference. There is more to this game than whimsy. The building’s miniature quality points to the converse need for scale in the ward block. It also refers to the graphic conventions of architecture, which involves in its invention a constant shuttling for clients and designers and builders between different scales and modes of representation. This witty architectural ornament, then, is a trace of its bigger self. It is also a marker of a historic moment in the development of the Sunshine Hospital complex, for the ward building is intended to expand laterally at its the western end, and in doing so will become an entity different to that recorded in the model.

Such architectural games may seem at odds with the po-faced seriousness of much hospital architecture, past and present. But smiling is good for you.

Dr Paul Walker is a senior lecturer in architecture at the University of Melbourne

Project Credits

Architect Lyons—project team Peter Bartlett, Chris Downing, Corbett Lyon, Cameron Lyon, Carey Lyon, Rob Tursi, Neil Appleton, Myles Lauritz, Barbara Bamford, Gillian Moody, Svetlana Johnson, Andrew Mathieson, Anthony Chan. Client Department of Human Services/Western Health—client representatives Leon Moran, Leanne Chappell.

Project Manager Atkinson Project Management.

Construction Manager Baulderstone Hornibrook.

Structural/Civil Engineer Barry Gale Engineers.

Building Services Engineer Kuttner Collins.

Landscape Architects Patterson + Pettus. Building Surveyor Philip Chun & Associates.