<b>REVIEW</b> MARCUS BAUMGART <b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> MARK MUNRO

Located on Gisborne’s main commercial street, the new supermarket acts as social and commercial infill. Overview looking northwest from the corner of Aitken and Robertson Streets.

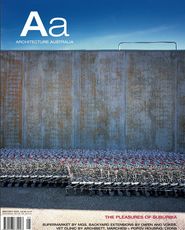

The supermarket’s cladding – stained, corrugated concrete panels – playfully responds to Gisborne’s rural context.

Looking along the verandah in front of the speciality shops, towards the supermarket.

The building nestles into its location, with the detailing of the articulated corner referring to structures in the town and region.

Facade detail.

Interior views. Strip skylights, integrated with the roofing system, bathe the supermarket sales floor in daylight.

THE COLES supermarket in the Victorian town of Gisborne, by McGauran Giannini Soon Architects, is a tapestry woven of many subtle, small ideas. Together they amount to a layered work of architecture that is experientially modest, but with potentially far-reaching implications. In particular, the project demonstrates the possibilities of reducing energy use in a notoriously energy-wasting building type, when a willing client, a sympathetic tenant and an architect committed to research focus on the issue.

The project appears conventional enough – take a site in a small town and provide a new full-line supermarket together with a collection of smaller retail premises. However, the Gisborne supermarket has a unique foundation. Before beginning the project a study was undertaken to determine its likely economic and social impacts. This found that, faced with the lack of such a facility in town, residents were making 40 per cent of their purchases in the neighbouring town of Sunbury – revenue was being taken out of the Gisborne economy and the increased vehicle use meant the consumption of more fossil fuels. The study concluded that, contrary to the perception of supermarkets as an overbearing presence in the economic landscape of small towns, a new supermarket in Gisborne would provide a net gain of local jobs and keep more revenue within the local economy.

The choice of site for the supermarket was also in keeping with social sustainability objectives. New full-line supermarkets are typically introduced to small towns on peripheral greenfield sites, taking advantage of unconstrained conditions. In contrast, this site is located in the centre of Gisborne, at the northern end of Aitken Street, the main commercial street. Rather than drawing activity away from the town centre, the supermarket acts as a social and commercial infill, continuing the high-street activities of Aitken Street.

The planning of the site responds to several ideas. The bulk of the supermarket is held back from the street edge, giving prominence to the new municipal swimming pool located immediately to the north. The eastern and southern edges of the supermarket building mass are occupied by a series of smaller retail premises that create an active edge around the perimeter of the building, effectively minimizing the blank walls so typical of this building type. Generous verandahs flank these shops, their form referencing historical precedent in the town. They create new social spaces for casual meeting, local fundraising drives and other such activities, and form a path drawing pedestrians from Robertson Street on the south to the swimming pool on the north.

The landscape of the car park has been designed as a green forecourt for the supermarket, with extensive planting and contextually appropriate agricultural fencing and edging details. Stormwater is channelled into broad swales, allowing the ground and vegetation to naturally filter run-off before it enters the town’s stormwater system. The landscape is fully irrigated by water harvested from the roof and stored in underground tanks; this water is also used for toilet flushing.

Beyond the social sustainability objectives, the architects were faced with a notoriously energy-hungry facility type. Australian supermarkets account for a staggering 1.8 per cent of our total energy use in this country. Any demonstrated reduction in the supermarket’s use of energy is of significant benefit.

The Gisborne supermarket tackles energy efficiency on many fronts. One of the key points of energy wastage in standard supermarket design is the interface between the front and back of house, where a temperature differential is created between the airconditioned shopping space and the unconditioned service spaces. The negative effects of this are exacerbated because the back of house typically leaks heat and energy like a sieve, pushing up the demand for heating and cooling on the customer side. In Gisborne this has been tackled by a raft of measures, including the use of soft baffles around loading vehicles and quick-action roller shutters to exterior loading spaces, both of which minimize energy leakage. Another major innovation in the project is the combination of refrigeration and airconditioning systems, a seemingly obvious strategy, but one that is rarely used. This reduces plant equipment and lowers running costs, further reducing the energy footprint of the facility.

The structure of the supermarket utilizes a heavily insulated sandwich panel system, limiting energy transmission. The roof employs the Kingspan roofing system, which uses insulated panels with high R-values and requires less structure to support it. The roof is supported on bonded recycled plywood box beams that have a far lower embodied energy than their steel equivalent, but can achieve similar spans. Lightweight Danpalon inflatable ductwork is suspended from the box beams, distributing air from the airconditioning system.

Strip skylights, simply detailed and integrated with the roofing system, provide a large amount of daylight to the retail space. This has two benefits. Firstly, the need for fluorescent lighting is reduced, with single-lamp fittings used in lieu of the standard double-lamp fittings. Secondly, as demonstrated by UK supermarket chain Tesco, shoppers are more likely to visit and shop longer in stores with natural lighting.

Taken together, the raft of energy reducing measures in the design and operation of the facility has resulted in an astonishing 39–40 per cent reduction in energy use across the supermarket. Given the amount of energy consumed by Australian supermarkets overall, the implications of this cannot be overstated.

Architecturally, the Gisborne supermarket playfully explores texture, colour and form to create a contextually grounded composition. The form of the verandahs and the expressed steel parapet on the corner of the building refer to structures located in the town and surrounding region. The red-stained plywood and corrugated, oxidizationstained concrete panels visible from the street, combined with the detailing of the verandahs and eaves, have an agricultural directness which also responds to the context.

The overall effect is of an understated and carefully composed collage of elements, a series of contextually driven moves that tease at the edges of the built form rather than drive it. There is no “big idea” defining this architecture. This can be understood as both a positive and negative attribute. On the one hand the building nestles comfortably in context, well “stitched” into the urban fabric it occupies, modestly doing its job. On the other, given the tremendous gains in energy efficiency the project represents, and its potential to revolutionize the way supermarkets are designed and constructed in Australia, one cannot help wondering if the project could have been less modest and more expressive architecturally.

Overall the project successfully poses the question: does the desire for social and environmental sustainability in a delicately balanced urban environment demand a form of contextual camouflage, or is there scope for a more searching and expressive creation of architectural form? Regardless of the answer, this supermarket will remain a responsible citizen, owing its first allegiance to the urban and social fabric of Gisborne.

MARCUS BAUMGART PRACTICES ARCHITECTURE IN MELBOURNE, AND TEACHES DESIGN AT RMIT UNIVERSITY. HE IS A REGULAR CONTRIBUTOR TO DESIGN PUBLICATIONS IN AUSTRALIA.

Project Credits

Architect McGauran Giannini Soon— design director Robert McGauran; project architects Davis Kunciunas, Paul Dash. Structural and civil engineer Clive Steele Partners. Landscape architect EDAW. Builder S.J Higgins.

Services engineer Robinson Consulting Group.