The attractions of city centres, including their proximity to high-value jobs and a vibrant social culture, continue to draw people closer together. Simultaneously, our current climate emergency requires us to reduce emissions and waste. Choosing to live in an apartment rather than a house can lessen our environmental impact by reducing loss of productive farmland and wilderness, and reducing the amount of energy required for heating and cooling. In addition, investment in mass transit decreases car use, and tree planting decreases urban heat and makes walking or cycling a more attractive alternative. The benefits of these investments increase with more people living closer together. Capital in the financing of building also encourages concentration and resists thinly spread development. In this context, the benefits of tall buildings seem clear.

However, unless well-designed and appropriately located, tall buildings can degrade rather than improve the urban environment. They can cause overshadowing and make streets and parks unpleasantly windy. Residents’ health can be affected by noise and air pollution. A lack of natural cross-ventilation and poor access to sunlight leads to a reliance on artificial heating and cooling, which is costly and causes more emissions. The need for lifts, the use of materials with high embodied energy and more energy-intensive construction can increase rather than decrease our contribution to climate change. Poor design can ultimately prejudice a vibrant social culture.

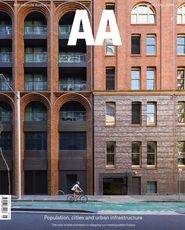

Designing tall buildings is a difficult task but the potential social and environmental rewards are great. In central Sydney, Arc by Koichi Takada Architects is an example of a tall building that increases urban density in Australia’s most productive location, among highly valued cultural institutions, thriving night-time entertainment, governance, law and finance.

Arc is the product of a City of Sydney Design Excellence Competition. This process, initiated by the City of Sydney in 2013 to elevate design quality, ensures not only that designs have been interrogated by experts but also compared to other architectural designs in a competitive process. Winning designs must demonstrate innovation, command of craft, control of building economics, amenity, communicative aesthetic and synthetic integration. Such competitions drive architectural culture forward.

A curving, steel-ribbed pergola frames views from the roof terrace to the harbour and surrounding metropolis. The pergola also animates the roof, civilising an often forgotten dimension of the city.

Image: Tom Ferguson

The building sits around a T-shaped network of walkways lined with cafes and shops that link Kent and Clarence streets to Skittle Lane. The transverse lane divides the building’s two faces, allowing each of the four facades to match the height and major string-courses of its neighbour. The apparently easy deference fits the building almost unnoticed into its locale.

Set among the brick warehouses of the western side of the city, Arc is a celebration of hand-laid brickwork. However, at first glance, there is something odd about the thinness of the arches, the exaggerated corbelling and the exactness of the aligned perpends. The bricklayers were well practised; they had previously created the contorted facade of Gehry Partners’ Dr Chau Chak Wing Building but they found Arc an even greater challenge, where any errors could not be hidden in design idiosyncrasy. They rose enthusiastically to this challenge.

Arc’s three brick buildings surround the laneways at varying heights (between eight and twelve storeys) and contain a hotel of eighty-five serviced apartments, entered from Kent Street at the lower-ground level. Another eighteen-storey structure of metal and glass contains 135 apartments and sits above and set back from the masonry structures, disguised by a mirrored ceiling over the laneways from which hangs an illuminated work of art by Ramus. Its two wings sit transverse, above the noise of the street, spanning the major walkway and keyed into the varying heights of the brick buildings below. A central steel-framed core rises between the wings. The setback interruptsthe downdraft, protecting the street from wind.

The glass and steel towers include an unusually high proportion of space devoted to communal use.

Image: Martin Siegner

Entered from the upper-ground level walkway, the upper apartments share a roof terrace with views over the city centre to the harbour and surrounding metropolis. A curving, steel-ribbed pergola animates the roof, civilising an often forgotten dimension of city life.

The bedrooms and living rooms open out across the streets, with the minor rooms adjacent to the corridors and light courts of the site’s interior. The corner apartments are naturally cross-ventilated through windows. Cross-ventilation aided by air cupboards and ceiling plenums in other apartments is sufficient but does not match the cooling and air cleansing effect of a gentle natural breeze induced by windows on different sides of a building. The interiors demonstrate the same thoughtful arrangement and material choice as the exterior, ensuring that the character of the development is seamless and complete.

Arc is a demonstration of how tall buildings can contribute positively to city centres. It is fitted carefully within a continuous area rather than standing apart. Its multiple uses are appropriately located: commercial use close to the street and residential use further away from the noise and pollution. The materials and construction are enduring, finely detailed and show the handiwork of their creation. It improves and expands the public spaces of the city. The architecture lifts itself through competition, civic thoughtfulness and clarity to render the city a delight to live in.

— Peter John Cantrill is an urban design program manager at the City of Sydney. Opinions expressed in this article are his own and not those of the City of Sydney.

Arc is built on the land of the Gadigal people of the Dharug Eora nation.

Credits

- Project

- Arc

- Architect

- Koichi Takada Architects

Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Consultants

-

Bricklayer (masonry subcontractor)

Favetti Bricklaying

Builder Hutchinson Builders

Facade engineers Inhabit, Surface Design

Masonry facade engineer AECOM

Structural engineer Van der Meer

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Commercial, Residential

Type Multi-residential, Tall buildings

Source

Project

Published online: 3 Dec 2019

Words:

Peter John Cantrill

Images:

Martin Mischkulnig,

Martin Siegner,

Tom Ferguson

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2019