FUTURE POSSIBILITIES

Melinda Payne & Philip Goldswain

Archipelagos

To sum up the state of play of Australian architecture from a survey of the annual award winners is no easy task. Any attempt at reconciling the diversity of what Philip Goad has described as the “archipelago” of Australian architectures is similarly fraught, when faced with the broad range of programs, contexts and concerns that have informed the projects. It’s also unhelpful simply to reinforce the “recognize and celebrate” mandate of the Institute’s awards program here.

We have, therefore, sought to bring another judgment to bear upon the awards, one brought from outside the processes of the day-to-day making of architecture. Ours is a perspective burdened instead with the difficulties of architecture’s teaching and advocacy, a perspective attuned to engaged architectural methodology and to projects in which we see new modes of civic, cultural, political and domestic life.

This means that there are many impressive buildings in this year’s national awards that won’t be discussed here. We are interested in the projects that offer an intelligent, insightful commentary on contemporary social and cultural concerns. They demonstrate new modes of practice and advance an understanding of the architect as an agent for positive social, environmental and cultural change. Such projects are exemplars, promising reverberations in the future.

Urban engagement

In a departure from previous years, the public architecture award winners confront the challenges (and opportunities) of the city and its public realm. In this age of urbanization, there is clear evidence of the importance of architectural knowledge in resolving the complexities of infrastructure and civic projects set within the difficult fabric of our cities. The singularity of WOHA’s proposal for their Bras Basah MRT station in Singapore – a water roof as lightwell, passive cooling device and reflection pool – is poetic, clever and sensitive to its historic context all at once. FJMT’s compact social condenser – encompassing library, childcare and community facilities – shields its users from a busy inner-city street as well as providing a small urban park. Hassell’s Rail Link Intermediate Stations use an understated architectural language as a dignified and generous introduction to the public transport network. The Melbourne Convention Centre, a joint venture between Woods Bagot and NH Architecture, occupies its piece of frayed urban fabric without displaying the unitary form of its near neighbour, Denton Corker Marshall’s Melbourne Exhibition Centre. Instead it revels in the awkwardness of this fit, triangulating its urban form into sculptural interiors.

Sustainability

As well as the pressing concerns of the metropolis, there is an increasing focus on the environmental impacts of building.

However, the sustainability category of the awards seems increasingly anachronistic.

It hails from a time when environmental concerns were considered eccentric rather than mainstream and sets up the preposterous binary wherein projects from other categories would then be somehow “unsustainable” – an obvious nonsense. Sustainability is a catch-all for a broad range of concerns but is now widely accepted to form the basis of any definition of good design. The judges appear to share this ambivalence, awarding sustainability prizes to projects that had already been acknowledged in other categories as significant pieces of architecture. The breadth of possible engagement with the notion of sustainability is evident in the comparison of FJMT’s technology-driven Surry Hills Library and Community Centre and NMBW’s low-tech “build less” approach to their fitout of the Lyons Architecture Office. These divergent approaches both nevertheless result in projects of great generosity and eschew architectural asceticism.

Palimpsest

Notable interventions in the heritage category are bold rather than deferential and are sophisticated in their design approach. Using new insertions to celebrate the heritage of a site allows the past to make a far richer contribution to current cultural experience than the fastidious preservation of museum pieces. In both the Paddington Reservoir and the Barcaldine Memorial there is interrogation and interpretation of the historical fragment in light of contemporary concerns to generate an instructive dialogue between past and present, and its future potential.

These projects evince, too, the agency of the architect in challenging the brief and employing initiative. It’s staggering that the original reservoir brief had assumed a “cap and grass” outcome for those extraordinary subterranean chambers. We wonder how much poorer the community and its urban context would have been with that result.

Similarly, it’s difficult to imagine the brief for the Tree of Knowledge ever contemplating as compelling an outcome as that delivered by Brian Hooper and m3architecture in Barcaldine. This powerful and enigmatic monument represents a significant architectural achievement in its own right and yet its contributions to the civic life of the local community and to the annals of our national history seem the greater achievements. Both in its skilful and resonant interpretation of a unique historical remnant and in its contribution of a high-quality civic space to a small country town, the Barcaldine project demonstrates the potent impact of the architects’ commitment and tenacity, when harnessed with the support of the local community.

Hybrids

The Robin Boyd Residential Award winner – Trial Bay House by HBV Architects – is without question a fine piece of architecture, but its preoccupation with formal concerns perhaps limits an understanding of a more progressive position for architecture, evident elsewhere. In their hybridized states, Lyons’ Lyon Housemuseum and Donovan Hill’s Z House ask more difficult questions about the nature of domesticity. Conceptually rich, programmatically challenging and formally bold, the Housemuseum offers an intriguing tension between living and exhibition spaces. The domestic seems peripheral at times, displaced to the project’s edges by the insertion of the “black” and “white” cubes of contemporary art display. Tension in the relationship derives from a shifting emphasis between the domestic and the institutional, and the result is an unstable reading of the house.

A similar sense of instability is found in the architecture of the Z House, which continues the practice’s exploration of the gradients between public and private space in the domestic realm. On a steep slope in Brisbane, the project tests the courtyard house, the terrain and the prospect as ways of engaging architecture and landscape. This test is conducted through the device of the central courtyard and the layered section, the facade and the architectural devices of furniture and aperture. These aren’t the only projects to show interest in hybridized, unstable states.

Justin Mallia’s commended multi-residential Yan Lane shows how a thoroughfare is transformed into a studio/house, and how easily a garage becomes an office.

Architectural intelligence

It is not a unique observation that the pursuit of purely formal concerns (the rather empty obsession with object making) represents a somewhat indulgent and unsustainable mode of contemporary practice. Heroic formalism is increasingly unviable as a preoccupation for the architect, in view of the scale and intensity of the issues currently confronting us: climate change, energy use, housing affordability, ageing infrastructure, social equity and myriad other challenges.

This is not to say that the profession must collectively don their hairshirts or that there’s no room for wit and whimsy, beauty and delight. There is much of this to be had in the awards and it is welcomed. We are reminded of Shane Murray’s remarks, however, that architects should be concerned with the worth of their contribution, not their market share. Architectural intelligence deployed in confronting these challenges is a contribution worth awarding.

Philip Goldswain is associate dean in the Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts at the University of Western Australia. Melinda Payne is associate to the Government Architect of Western Australia.

IT’S A NUMBERS GAME

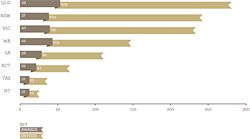

1. NUMBERS OF ENTRIES AND PRIZES BY STATE

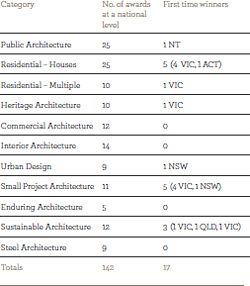

2. TOTAL AND NATIONAL AWARDS ENTRANTS BY CATEGORIES

3. FIRST-TIME ENTRANTS & WINNERS BY CATEGORYStatistical analysis provided by Mei Soon MBA.

Eli Giannini

Informed, or should I say warned, by the recent Australian elections and assisted by one of my colleagues, I present here a little number crunching on the state and national awards results. Every year architects offer their most prized and hard-won creations for scrutiny by their peers. The winning projects, all products of our contemporary culture, have travelled along roads as unique as the professional path pursued by each jury member. Or have they? My motivation for delving into this year’s national awards is simply that I would like to see the rich diversity of contemporary discourse reflected in the variety of projects chosen by the juries. Our own cultural health depends on the architectural diversity we are able to encompass.

The next generation, we are told, is dispensing with the voice of the expert, preferring instead to take its chance in straw polls conducted via Twitter and blogs. So it may be that in the future we will enjoy extreme diversity. Or perhaps quite the contrary, as world domination by the most media-savvy leads to a narrowing of horizons, where the winners will be of the one-size-fits-all variety.

Conscious of the fact that even the architectural profession may end up with a hung parliament by giving everyone a vote – don’t laugh, the more-same, more-same problem is present in all architectural and industry media – I want to shed light on a few basic facts of the awards process.

This year, the largest number of state award entries is from Queensland, followed by New South Wales and Victoria, then Western Australia and South Australia, and finally the Australian Capital Territory, Tasmania and the Northern Territory (Fig 1). It seems, from the numbers, that Queensland has a very healthy system in place, which allows regional areas to participate in the competition. This is surely a good thing for the promotion of architecture. Queensland also takes a good swag of prizes in the national competition, proving that quantity isn’t necessarily the enemy of quality.

Looking at all categories common to state and national levels, the proportion of premiated entries in each differs greatly from state to state. Generally speaking, the larger the category, the smaller the portion of projects in the prize pool. For example, projects entered in New South Wales and Victoria have the least chance of being awarded at state level because the overall number of projects in these states is larger. Setting this aside, however, there is a significant divergence in the proportion each state decides to award within each category area.

New South Wales, for example, only gives awards to 6.3 percent of its total single residential entries, while in other states 13–50 percent of the projects entered are premiated.

In fact, the single residential category is perhaps the hardest done by when we see how judging plays out in the competition. This year only three prizes were awarded in the national residential category, from an original pool of 205 state entries and twenty-five national entries. In my opinion this number is too small to display the diversity of design practice and the quality of output in this country.

One reason for the large number of entries in this category is that residential new and residential renovations and additions are both entered. The majority of the profession practises almost exclusively in this area, which also adds to the category’s popularity.

I can only speculate as to why the prize pool is so small. Perhaps juries are not well equipped for doing the numbers when confronted with riches of choice. They may also feel that erring on the side of generosity will brand them as indiscriminate, so they award the expected maximum of four or five prizes, no matter the circumstances.

I suggest that a more critical overview is needed to counter this practice in future state and national programs. The last national reform of the awards program led sensibly to the introduction of a new prize for small projects, a separate category for multiple residential projects and better integration of state and national awards and prizes.

Perhaps this reform should continue. Splitting residential new from renovation and additions would increase the prize pool and give greater variety of judging in the residential categories.

Public architecture is also poorly premiated in New South Wales, while Victoria and Queensland were particularly reticent to grant interior architecture prizes. Urban design proved a popular category with juries in New South Wales and Queensland, while Victoria awarded only 18 percent of its entries in this category, less than half the number of winners New South Wales delivered at state level.

Heritage was well represented throughout, with 30 percent receiving an award. Projects in the sustainability category were least premiated in Queensland and Victoria (around 25 percent) by a factor of two in comparison with other states, which does not reflect the need for sustainability in either place.

My favourite statistic, and perhaps the one I would pick as the litmus test for the health and wellbeing of the whole system, is the one showing first-time winners. How many projects by architects not previously awarded reach the national competition?

This year there were seventeen, of these five in residential and small respectively. What is interesting from a national perspective is that more than 60 percent of these come from Victoria. Is this a reflection of the judging process in this state or its greater number of new practices or both? Looking across the board, a particular disappointment for me was witnessing the great depth and quality of the Victorian multiple residential category getting lost in the judging process at both state and national levels, despite a good effort by the state jury to award a larger number of entries.

The interior, public and commercial categories also lost depth in the final outcome despite the excellence of the winning projects.

This is clearly illustrated in Fig 2 when we consider the number of winning projects at national level as a proportion of number of entries for the different categories.

Post-mortems done somewhat remotely from the subject may not be 100 percent accurate but I hope this delivers a heartfelt plea for a more expansive outlook by the juries. Short-listing too narrowly or basing decisions purely on the success of the photograph isn’t enough to deliver the diversity we need. Visiting more projects in the future is essential and the only true way of determining if a project is worthy of consideration for an award.

The Australian Institute of Architects awards program is a way of highlighting the creativity and excellence that exists in Australia. The work must be judged by those who can understand and appreciate this diversity.

Eli Giannini is a director of MGS Architects in Melbourne.