Instant urbanism – just add water

Sydney does great theatre. Forget Cate Blanchett and the Sydney Theatre Company down at Walsh Bay; it’s the tortured unfolding of the city’s urban design that provides the most affecting show in town. Often resembling a Theatre of the Absurd, sometimes even a Theatre of Cruelty, the processes of design, debate and development for Sydney’s major urban projects are consistently contentious and divisive. With the Opera House as an epic urtext, the redevelopment or reimagining of Woolloomooloo, Darling Harbour, the MCA and a number of other important sites in the city have been tales of grandiosity, volatility, voraciousness and sophism. Most often it’s been the Theatre of Lost Opportunity.

The redevelopment of Barangaroo is the latest production in town. For the past seven years or so the conversion of the former East Darling Harbour container wharf – a twenty-two-hectare, pile-borne concrete apron capping a murky substrate of contaminated fill – has provoked angry debate. The basic process so far has seen the NSW State Government take control of the site and orchestrate a competitive masterplanning procedure involving developer-led design consortiums. The following is a very brief sketch of the project’s evolution and a consideration of some of the key issues to emerge from the debates around it.

In 2006 Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban Projects, Paul Berkemeier Architect and Jane Irwin Landscape Architects (HTBI) won the two-stage international design competition for East Darling Harbour (see Architecture Australia November/December 2005 and July/August 2006). However, from late 2006 the team was excluded from the ongoing development of the site. Barangaroo (as it is now known) was subsequently listed as a state significant site, bringing it within Part 3A of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act and exempting it from conventional planning processes.

The Barangaroo Delivery Authority (BDA) was created and a series of modifications to the concept plan approved: creating more coves, consolidating development in the south and segregating the northern parkland.

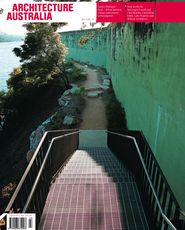

Overview of the preferred scheme for Barangaroo South, by Lend Lease with the design team led by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.

In December 2009, the NSW Government announced that Lend Lease had been selected as preferred tenderer to develop and create the $6 billion Stage 1 development. Lend Lease’s design team still included Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, the key partner in their highly commended competition scheme of 2006. In fact, in February 2010, when the winning proposal went on public exhibition, it was clear that the “modifications” to the successful HTBI scheme had effectively exhumed the runner-up’s corpse (not without signs of decay).

The slick digital sheen of the BDA’s website offers an uncomplicated, edited account of these developments (for example, all reference to the original competition is gone), but that surface veils a fraught public and professional engagement with the project. In a variety of media and forums there has been disquiet over the contentious changes to the initial competition-winning masterplan, the extraordinary escalation of the development’s scale and competing notions of Sydney’s heritage and its civic identity, as well as broader, uncomfortable questions about the fate of public life in the contemporary city. There are multiple strands in the fractious debates taking place, encompassing professional divisions, personal grievances, political sophistry and civic aspirations. In untangling some of those strands it helps to see them in relation to two facets: process and form.

Process

Starting with the most personal issue for key actors in this drama, the unfolding of Barangaroo has put into question the integrity and worth of the competition process. Former prime minister Paul Keating, whose investment and influence in the project have been as dramatic as they have been pervasive (chairing key panels and publicly spruiking his own vision), categorizes HTBI’s eventual exclusion from the project as a simple case of “iteration.” He describes the original competition as being simply about ideas and suggests that HTBI refused to engage with the process of change necessary for its scheme’s realization. HTBI, on the other hand, has documented a set of uncredited work that effectively produced the approved concept plan, as well as a lack of basic professional protocol and communication on behalf of the client body. Client–designer relations can break down, and the completion of competition-winning schemes is never guaranteed, but the dubious processes involved at Barangaroo are disconcerting evidence of the way in which the city’s major developments are handled by government agencies.

The waterfront promenade from the preferred scheme by Lend Lease with Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.

Perhaps more disturbing is the chorus of voices (including other architects) who accuse HTBI of naivety and hubris. A critique has emerged suggesting that, despite the merits of their masterplan, the team could expect no more than the treatment they received: “City building is a vicious game,” the voices admonish. Again, architects must be able to articulate the strength and worth of their ideas but they can also expect and demand professional processes. The cynicism and ugly victim mentality that suggests it’s simply the architect’s lot to be exploited condemns the profession to further irrelevance.

At a broader scale, Barangaroo has underscored controversial issues to do with the state’s planning processes. As a major project deemed to have state significance, the project is being assessed under Part 3A of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979. Introduced by an amendment in 2005, Part 3A reduces community involvement in the decision-making process and seeks to minimize the risk of delay or obstruction to a project by limiting the possibilities for review. Instead, the Minister for Planning maintains the power to make all key decisions, with advice from “expert panels,” limited input from other key agencies and scant opportunity for effective criticism.

At Barangaroo this contributed to a situation where the original floor area was increased by 30 percent in the revised masterplan issued with the Request for Detailed Proposals (RFP) for development rights to Stage 1. The subsequent nonconforming scheme proposes a further 15 percent increase on top of that, plus a 213-square-metre hotel outside the approved masterplan envelope. Based on that proposal, Lend Lease has since signed a contract gaining control of seven hectares of crucial city foreshore. However, the masterplan is still largely opaque to the public; key details such as the approved floor space, floor space ratio, ownership plan and the area of public domain to be dedicated to the city or other public authority remain unknown. It seems perverse that a development of such scale and importance should be subjected to less, rather than more, scrutiny.

Transport Place from the preferred scheme by Lend Lease with Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.

Continuing the concern with process, Keating characterizes the 1960s development of Barangaroo’s concrete apron (particularly the ports and railways) as an act of “industrial vandalism” perpetrated by the tsars of industry who ruled Sydney at that time. He contrasts that autocratic process with his supposed championing of the public’s interest in the redevelopment of Barangaroo as a “new financial district.” However, little seems to have changed in fifty years except for the shift from industrial activity as the city’s development driver to post-industrial activity: the mega-floor plates of the burgeoning Australian finance industry replacing the concrete pad of the container port. The other process advocated by Keating, as a blunt revision of the historical processes that have impacted on the site, is the construction of an artificial headland at its north end. This is Keating’s baby: the centrepiece of a vision that encompasses a larger rejuvenation and remediation of the harbour’s headlands to some imagined Arcadian state.1

Form

Indeed, ideas about vision have largely driven discussion of Barangaroo’s form, especially as the concept plan has been modified over 2009/2010. At one end of the spectrum (and site) is that concept of Keating’s: the bucolic grassed hill concealing a car park. At the other end are the calls for “world-class architecture” and new “icons” for Sydney: desires for a spectacular waterfront skyline enhancing Sydney’s profile as a global city. The successful Lend Lease proposal contributes dramatically to this with its fifty-storey hotel, described by Richard Rogers as a “unique landmark tower on a public pier” and by Keating as an “exclamation point.”

However, leaving aside questions about the historical perversions of Keating’s faux-headland and the laughable assertion by Rogers that a 213-metre-tall hotel can “touch the water lightly,” the most interesting thing about the debates over form has been the strange sense of scale at work. The site is twenty-two hectares, a sizeable portion of the city centre, yet most architects and commentators have approached it as if it’s a singular, homogenous form – an object to be moulded in one step, by one hand. As such, largely irrelevant discussions are conducted about matters such as whether a straight or curvy edge to the waterfront will be more appealing, neglecting the perceptual scale at work on such a large site as well as the accretive process that characterizes the emergence of city form. Ed Lippmann (a member of the second-placed competition team) demonstrated this well when labelling the HTBI scheme as “little more than a subdivision plan.” His assessment points to a key misconception: the subdivision plan is not just a prosaic partitioning of the site but a critical tool for successful masterplanning. Urban design is not just big architecture.

Globe Street from the preferred scheme by Lend Lease with Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.

Ideas of the city

This distinction between urban design as the creation of an armature for development over time versus the design of city-scaled form is at the heart of differences between the HTBI masterplan and the Lend Lease / Richard Rogers scheme. It is not simply the choice between a more or less sexy vision; the formal differences embody contrasting understandings of the public realm and the incremental transformation of cities.

The HTBI masterplan was predicated on a clear distinction of public and private development – a traditional urbanism of public streets defining private development lots. It also worked at producing a finer grain of development – smaller lots to enable more diverse ownership, land value and uses, sitting within a framework of streets making as many connections as possible to the existing fabric of the city: an urbanism of rich moments. As a development strategy it assumed multiples stages and an ongoing control of land release by the government to yield gains in land value. It is an urbanism often criticized for being conservative and dogmatic, but it at least maintains high aspirations for the public realm and the quality of public life in the city. Its structuring of an urban “armature” may be unfashionable, but it also contributes to an ongoing adaptability.

The Canal from the preferred scheme by Lend Lease with Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.

By contrast, the Lend Lease / Richard Rogers scheme agglomerates the development footprint overwhelmingly in the southern third of the site (Stage 1). It does this in much larger building parcels, focused on providing the large floor plates demanded in the current commercial market. This also reduces the number of public streets and concentrates movement between the site and city into a few key connections. These feed a ground plane that is much more open and suggestive of a privately managed corporate plaza, rather than public streets. The larger development sites, and their bundling up of building and landscape, aid a strategy where the government quickly divests itself of the development responsibility to a single developer and reaps an immediate financial return – an instant urbanism: just add water.

Assuming something very similar to this proposal is realized, it may provide a cash injection for a hard-up state government but it is difficult to see how the masterplan can help produce the kind of urban life that Sydney should expect from Barangaroo. Its current scale and structure forego the kind of fine-grain urbanism that the city is struggling to reinstate in its centre, the vagaries of the “cultural” components suggest those buildings will slip away during development (how many struggling cultural institutions are there already in Sydney?) and without a serious residential component the mix of uses will be low. Right now it is hard to imagine anything beyond a spectacular corporate quarter, with a carefully stage-managed sense of colour and movement. Rem Koolhaas’s 2002 essay on that kind of total environment neatly describes the effect of its creeping control over the whole of the city’s fabric: “Junkspace reduces what is urban to urbanity … Instead of public life, Public SpaceTM: what remains of the city once the unpredictable has been removed.”

But the headland park will be a very pretty place to contemplate all this from …