This new building at the University of Melbourne houses cutting-edge immunology research facilities, with Nobel Prize Laureate Professor Peter Doherty as its patron. The building has been designed by Grimshaw in collaboration with Billard Leece Partnership and boasts healthy credentials, a very healthy budget and an expanding field of research enquiry – making its presence and future assured. The sponsorship of the project is collaborative: a partnership between the University of Melbourne and Melbourne Health, it has received funding from the federal government’s Education Investment Fund as well as the Victorian Government. It has also received input from the World Health Organization (WHO), as the home for the WHO’s Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza. A mix of highly specific medical research, academic functions and opportunities for public engagement, the building is the public face of The Doherty Institute. I’m calling it a public building because its funding and intentions are for public benefit.

The Doherty Institute sits on a prominent corner in the expanding health and academic precinct on Royal Parade in Melbourne. It occupies the former site of the rather iconic, but latterly bastardized Ampol House – a very public site with three street frontages.

At the time of writing, the building was at handover stage and so was not yet occupied; therefore my commentary and comments can only be read as projective of its inhabitants. Nonetheless, given some understanding of the nature of the various contained functions, the declared intentions of The Doherty Institute and the building’s presence in this prestigious and public precinct, my initial reaction is to ask my current favourite question: “Why does it look like that?” This line of enquiry examines what the rules of engagement are, seeks to discover what is being expressed and asks what this particular composition of built elements suggests to us about the nature of the activities contained and our relationship to those activities. This is not a pejorative exercise on my part – I believe that architecture tells us things about ourselves and prompts us to consider our place and presence. This is not to say that architecture is a language, but that I believe we “read” it, and that it does “act” upon us.

I notice the unevenly divided three-part north facade, the asymmetrically folded precast concrete panels of the east and west facades, the high-tech street canopy and the undulating ply-rib ceiling of the foyer space and two other spaces at mid-height and on the top floor of the building. I reasonably assume that each indicates different occupational and environmental conditions acting on the building. I am shown comprehensively through a very professional, polished response to a well-articulated brief. Everything is well reasoned, thorough and measured – not with a sense of rightness, more one of being “correct”. However, it seems to me that the issue for such thorough reasoning is that it lacks hierarchy – and our lives are hierarchical and differentiated.

The building contains facilities for medical research and academia and, with three street fronts, it is also the public face of The Doherty Institute.

Image: Peter Bennetts

The structure of the program and the identities of its composition are so well studied that in these instances, this structure, this control, starts to feel bureaucratic and self-confident, requiring nothing of me as the user. The building’s components seem to have the architectural equivalent of reason and professionalism that John Ralston Saul develops in Voltaire’s Bastards when he suggests, “the contribution [professionals] made to society was via their professionalism, which was an assertion of reason. And to possess reason was to be a responsible individual.”1 In this building, I am an individual but I am not required to act, as I sense the spaces feel no need for me to engage with them.

Much of this sensibility is established by the organization of the functions and the planning of the building, in both plan and section. But it also pervades the previously noted facade systems, the differentiation of structural systems between glazed lifts and occupied floor space, and the articulation of the various types of spatial identity – open offices, laboratory spaces with borrowed light, and the more enclosed heavily serviced areas. In this planning, the adjacencies and divisions are clear and should certainly give much clarity to the use of the building. Even the space and structure of social interaction within the building – the tearoom – is rational and thorough in its intentions, sizing and positioning; it can multi-task.

The tearoom on the fifth floor displays the rational order found throughout the building.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Given the nature of the research taking place within the building, the servicing is substantial and has therefore been influential on the planning, yet it has not been phenomenally instructive. Yes, it structures the planning but this influence is masked by the rational ease with which it is located. As with most of the building’s occupational clarity, the servicing locates, but does not influence or incite enquiry. The physical and functional elements of the scheme are positioned with pure reason, such that it seems our actions are contained by its competence and any relativism is smoothed over. There is little “experience” in our occupation of its spaces: we may want to be involved, but in a gentle way we are not allowed to. Ralston Saul describes it thus: “What are our expectations [of reason]? What is the mythology surrounding this word … Reason began to separate itself from and outdistance more or less recognized human characteristics – spirit, appetite, faith and emotion, but also intuition, will and, most important, experience … The Age of Reason has turned into the Age of Structure.”2

This building is, to some degree, undone by its own competence. In “solving” the issues of planning and servicing so eloquently as to seem almost obvious, it fits too fully into the “design as problem-solving” category. Ralston Saul laments, “Yet there is no great need for answers. Solutions are the cheapest commodity of our day.”3 I am not suggesting that architects shouldn’t solve problems, but rather that architecture, as the “thoughtful making of spaces,” is not as cut-and-dried as answers and solutions might suggest. A sense of edginess seems an appropriate character and symbol for buildings of this nature. Research involves – in fact, requires – change, exposure, risk, the willingness to be wrong, development, adaptation – characteristics that are constantly in flux. “There should be no need to act as if all decisions were designed to establish certainties,”4 and I sense – and suggest – that this should apply to the architectural experience as well. Research is about change, enquiry and opportunity, yet these run counter to my sense of the stable, reasonable character of this particular building.

Laboratories are positioned at the centre of the floor plate, with glazed walls admitting light and allowing views into the rooms.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Part of this reasonableness is predictability. It is what we have come to expect, and yet architecture should not merely be about what is expected. We need to be engaged by our environment. We architects, along with our clients, are now producing many highly competent buildings. There is nothing wrong with them and they are certainly not bad buildings, yet their competence does not engage us, and without engagement the user’s presence is not manifest. Do we lack the courage to embody an ongoing sense of enquiry through the spaces we create and through the ways we find ourselves positioned by buildings, spaces and places? Some things need to be counted; they cannot be just “ticked off” as done. I am not arguing for difference or inventiveness for its own sake, but rather the idea that architecture might be propositional.

Note: The Doherty Institute is an unincorporated joint venture partnership between the University of Melbourne and Melbourne Health. The Doherty Institute partners and their affiliates gratefully acknowledge the significant funding assistance provided by the Australian Government’s Education Investment Fund and the Victorian Government.

1. John Ralston Saul, Voltaire’s Bastards: The Dictatorship of Reason in the West (London: Penguin, 1993), 14.

2. John Ralston Saul, Voltaire’s Bastards, 14.

3. John Ralston Saul, Voltaire’s Bastards, 583.

4. John Ralston Saul, Voltaire’s Bastards, 585.

Credits

- Project

- The Doherty Institute

- Architect

- Grimshaw Architects

Australia

- Project Team

- Keith Brewis, Neil Stonell, Alex Matovic, Adrian Curtis, Gwyneth Choi, Cameron Conwell, Tam Dao, Gosha Haley, Stanley Kor, Joel Lee, Lam Le-Nguyen, Oliver Ness, Chian Quah, Anne Shui, Damon Van Horne, Mike Wu, Gilbert Yeong, Ron Billard, Ken Tsen, John Zbiegien, Belinda Andrews, Jimmy Chin, Sue Guzick, Sebastian Lee, Monik Patel, Sonya Radywyl, Stuart Webber, Elisabetta Zanella

- Architect

- Billard Leece Partnership

Australia

- Consultants

-

Builder

Brookfield Multiplex

ESD SKM-S2F

Hydraulic engineer CJ Arms & Associates

Main contractor Brookfield Multiplex

Project manager Donald Cant Watts Corke

Quantity surveyor Donald Cant Watts Corke

Services engineer SKM-S2F

Structural and civil engineer JMP

Workplace advisor DEGW, AECOM

- Site Details

-

Location

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Education, Health

Type Universities / colleges

Source

Project

Published online: 2 Jun 2014

Words:

Des Smith

Images:

Peter Bennetts

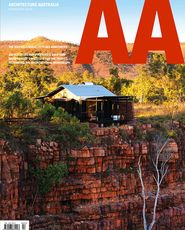

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2014