Young planetary nebula

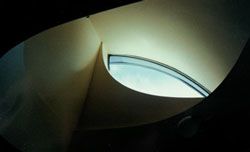

window at Brambuk Living Cultural Centre

Brambuk detail

nebula

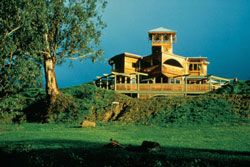

Eltham Library

Brambuk interior fire

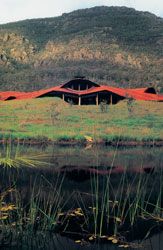

Brambuk overview.

Catholic Theological College, Eade St

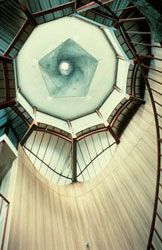

Catholic Theological College interior stair

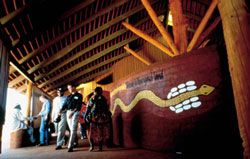

Uluru – Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre, leitmotif drawn in the sand – Anangu and rangers working together

Uluru – Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre entrance

Hackford House; Windhover Residence roof

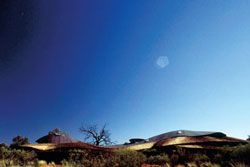

Uluru – Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre roofscape.

Catholic Theological College window

Uluru – Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre interiors

exit from the World of the Platypus

Imperial Austria Exhibition

concept sketches for Brambuk

Windhover stairwell.

We live in uncompassionate times. Australia is a country that is spiritually and culturally diminishing. An inability to mourn the past, to reconcile with the Indigenous peoples of Australia, and an unwillingness to embrace the world that trickles to our shores in leaky boats, speaks of fear, alienation and an undeveloped sense of the other. There is a dis-ease in this country, a muffled suffering: epidemics of depression, youth suicide and degraded environment are symptoms. And yet we continue to act as though nothing is wrong. On the whole, art and architecture do not pick up the social challenge. Nor is an aesthetic being developed that could hold such tragedy and suffering.

Some pertinent questions arise.

Firstly, how can we reconnect to our environment, to our community, to each other, to ourselves, in a culture that upholds pragmatism and self-interest as national goals? Secondly, what qualities of thinking and feeling would put architecture in a right relationship with society and underpin a renewal of openness, connectedness and compassion?

Thirdly, can architecture take up the challenge to help heal, nurture and illuminate our varied humanity in parallel with developing an ecological sensibility? Finally, is it no longer possible to imagine a socially engaged architecture after the social failures of rationalist architecture, particularly in the depoliticized and formalistic excesses of Internationalism?

Our times have sometimes been described as “post-human”, spawning an art and architecture of “separation”. Symptomatically, many important public buildings and precincts loudly proclaim individualism and iconic celebrity, eschewing the more complex and subtle aims of “fabric building” – a more feminine strategy of weaving and spinning (patching and mending) place for people, underpinned by values of serving and nurturing communities.

The success of global marketing can be measured in the predominance of consumer-driven notions of fashion, decor and lifestyle as desirable design values in art and architecture. There is, of course, a place for fashion-focused design. However, if it becomes the prevailing culture, an insidious draining away of vital energies can occur – what is called “sexy” is often entirely lacking in “eros”. Good taste conservatism fills the vacuum and risky art, difficult beauty, are marginalized.

What Colin St John Wilson calls the “natural imagination” has been eroded from its position as scaffold and foundation for the “artificial” or “cultural imagination”, leaving us with an often dryly intellectual and self-referential architecture, bereft of its roots in nature, the human body and the psyche. In the concept of the natural imagination, our own body, psyche and soul reverberate with the community body in infinite difference, in infinite recognition, and all are remembered in architectural form as human body – in what Adrian Stokes memorably describes as a limited language of forms “confined to the joining of a few ideographs of immense ramifications”. These “ideographs” are our most primal spatial experiences, universally intuited and understood.

The idea of the architect as social artist suggests that the architect has some responsibility for social health. It suggests that an architect works with the ecology of groups and communities, effecting change – working beyond the narrow confines of the individual into the future of humankind. Building is viewed as process, not only product. The process is a dance of constant negotiations. At the end, the trace of the dance is seen in the building. In this process the architect leads a complex collaboration that folds culture, place and people into a new relationship with each other, effecting transformation. If architecture is to be more than visual composition, theory or merely a commentary on “lifestyle” for a bored elite, we need to re-engage with society. As architects our buildings should do the talking. They should demonstrate, in use, what we’re on about. Articulating what we do, however, brings the challenge of finding a way of talking that parallels the work.

I would like to propose some ideas, which are of a poetic order – seeds or creation points, from which a practice and thinking could grow.

I have chosen six germinal words to start reflecting on the qualities and values possible and perhaps necessary for a contemporary Australian architectural practice. They are: the other, dance, care, presencing, shadow and mystery. Although I’ll be speaking to these themes in turn, I don’t see them as a fixed sequence; rather they are a dynamic mandala of key terms and relationships in the practitioner’s universe. Each one is precious because it symbolizes the multiplicity of the WHOLE. Each one holds as potential all the others. They are also intended to evoke a way of orientating to the world and a way of working.%br% THE OTHER NEGOTIATING THE SPACE BETWEEN%br% “We live in the currents of universal reciprocity”, writes Martin Buber.

Relation is reciprocity – the dance between I and thou. The in-between space, the reciprocal space of relation, is central to the process of making architecture. In the charged space of encounter, where the shock and surprise (delight and inspiration) of the unfamiliar jolt and shift our boundaries, the architect is negotiator and mediator to the otherness of people, place and culture.

That difficult terrain can be enlivened with play, movement and energy: eros can conjure, divert, humour and scintillate with strategies of connectedness which paradoxically loosen, unsettle and reconstellate.

Boundaries become permeable; an exchange takes place. This play across “otherness” involves respect of difference, not absorption. As architects we do not visit ourselves upon the other, but have an attitude of active listening, waiting for the invitation while offering the hand.

We are bodily confronted by otherness, with an immediacy that is unparalleled – boundaries float and fluctuate. We listen and commune across the moving boundaries of self and other; energies gather and form – a “third”, born in the middle ground of collaboration, mysteriously emerges. This “third”, born of conversation, empathy and free creative gift, expands the vision of both. Out of difference we meet and engender something new.

If “self” is to become a more fluid and permeable entity, we need to allow the ebb and flow, not only of other identities, ideas and cultures but also nature, to wash tidally across our boundaries. Landscape is the great Other in Australia and if we are to find relationship in a sustainable, respectful way to it, the development of an empathetic ecological sensibility is critical. Goethe’s question of the 1830s, “Is not the core of nature in the heart of man?”, has radical implications, which are echoed in much Australian fiction. Our literary writers have mapped the otherness of Australian landscape in fiction for a hundred years and contemporary writers such as Gerald Murnane and Tim Winton inhabit a postmodern sensibility where the landscape is deconstructed and reconstituted as complex self.

In Murnane or Winton, nature can dissolve into transcendent revelation or conversely, break chaotically in on the psyche, upsetting all notions of stable identity. The writers and painters have perhaps outstripped the cultural status quo in Australia, where too often nature is still viewed as the hostile other.

The wisdom of the traditional Indigenous relationship to the land is accessible tangentially, mediated by a sensitive poetics. Ecology, spirituality and the arts are making ground in this direction.

Architecture spans all the arts and includes culture, religion and philosophy within its context and so is also liable to the critical reflexivity of postmodern thought. The building, like the self, can be consciously deconstructed – its parts separated out and put back together in exciting and alarming ways, which challenge and confront set notions of the purpose of architecture, challenging history, culture and institutions to review themselves. Somewhere, however, in this “sea of otherness” one also seeks the intactness, repose and poise of empathetic relation in architecture.

One of the great possibilities of architecture is that we can find ourselves afresh in it – that its “otherness” does not overwhelm the fragile self, but instead inspires it in its transformative journey. Juhani Pallasmaa writes that silence is one of the enduring qualities of architecture – that silence emanates from its materiality, brought into a contemplative resolution of meaningful form.

The healing energy of architecture can derive from this quality, enabling an unfolding of our humanity. Identification (or “oneness”) and separation (otherness) are the two primal human experiences from which architecture derives. Finding the creative balance – the “play” between these polarities – enables us to see the building as self.

The pioneer American architect Louis Sullivan outlines a philosophy that underpins the stream of what he called organic architecture and what some of us call responsive architecture:

“[Our] … power to create is intimately based on [the] … power to sympathise, for sympathy is among [our] … powers … sympathy implies exquisite vision: a power to receive as well as to give: a power to enter into communion with living and lifeless things: to enter into a unison with nature’s powers and processes …

Sympathy, thus understood as power, is the beginning of understanding: for knowledge alone is not understanding.”%br% DANCE THE ALCHEMY OF CONNECTION%br% In architecture, human process, physical making and embodied expression are a dynamic and dancing continuum. Such a dance is not a fixed step, but a complex improvisation that takes imaginative light-footed consideration of many variables. Of course toes do get stepped on, there is the odd trip, the occasional embarrassing moment or, at worst, a change of partner! But the dance goes on!

As we move from the encounter between I and thou to an engagement with the multiplicity of other(s) involved in most of our work, a more complex challenge arises. Multivarious, unreconciled, scattered fragments wait for the ground to be cleared and the dance to begin. The architect, the pathfinder, steps forward and leads out, throwing body, psyche forward into space, risking all for the visitation of inspiration and grace, dancing over the pathless sacred ways. Dionysian intuition energizes the fragments, and the separateness that inhibits begins to loosen. Care and community and the making of place begin.

About the multiple spiralling centres, a dynamic shifting balance between centripetal and centrifugal forces scatters and gathers the restless fragments. The lie of the land is listened to and negotiated. There is the drama of encounter, the danger of attraction and the bridling of desire as each looks for repose, a home, in the restless gathering. From within the dance, connections are made; space and world are gathered in, the dance surges forward. When the relationships have found their dynamic balance, the architect steps outside and grounds them, places them.

The dance leaves its trace in the building, the residue of communion.

The dance might begin around a fire, in a clearing in the bush, storytelling, drinking, laughing, feasting. A gathering for a purpose.

To reclaim lost land, culture and dignity through imagining and building a living centre for five Koorie communities of ancient origin.

As the fire dies, I overhear, through the darkness of the tent in the middle of the cold night, men weeping. Whispered stories of unbearable suffering and self-doubt, of courageous and good humoured enduring together. In dreams that night, the broken pieces begin to tremble and flicker with new life, new hope, a new form. They begin to slowly circle with purpose and beauty, mirroring the rehearsal of dance in the movement of the stars.

The building shows the trace of the dance in its arcs and openings, its shadows and buckling, its lift and its bearing. The fireplace as centre holds, poises, as the spaces swirl about it, flowing one into the other, each having a centre but also sharing the centre of the whole – the fire, the heart of its community. The building embodies stories, from country to coast, of eagle, whale, eel and cockatoo, animating it and communing silently with the surrounding mountains, the creek, the bush and the distant ocean. At dusk the Ancestors’ spirits gather in the shadows, seeking refuge. The living descendants hear them, feel their support in their struggle for homecoming.

The dance may begin in a room, in an outer suburb, in a circle of Catholic seminarians, alight with their visions and aspirations. They plan to relocate their theological college to the inner city for the twenty-first century: a new building embracing an old building, to celebrate and support their Christian values as they inform education, human development and social justice, engaging with the culture of the city.

Their aspiration is for the old and new to dance together, with the spirit and with the senses; to rebalance the masculine and feminine; to renew the spirit of inclusiveness, tolerance and transparency, healing and reconciliation. Order is important, but also movement and flexibility, embracing change. Suggested sources for inspiration from the seminarians were surprisingly varied and even contradictory. They desired qualities ranging from the humility of St Francis, the tenderness of Fra Angelico, to the spiralling complexity of a Bach fugue. Weaving these strands would be all part of the dance.

The dance is seen in the building’s free flowing, unfolding gesture of connection, of reaching out into the world and conversely, drawing space in to itself as protected precinct. The surfaces follow a swelling and breathing of the inner space of the building – the basic pattern is the lemniscate, an architectural figure described by Goethe, “Nothings inside Nothings outside, For what’s inside is also outside Holy open secret.” ›› Mirroring the Church itself, the building is animated by one curve, many views in a state of becoming, striving for wholeness. A stair is the fulcrum of the dance and here as we climb, shadow gathers, gravity resists, while simultaneously, sunlight penetrates and light uplifts. In this space, the beauty and silence of Estonian composer Arvo Part is evoked. In his words, “This moment and eternity are struggling within us.” A new contract is drawn between place, architecture, community and spirit.%br% CARE THE GIFT%br% Barbara Tjakatu at Uluru enacts a sequence, unfolding revelations of space and perception. She treads lightly, running seeing fingers over leaf and bark. “Looking, looking, touching, touching,” she says. Feet, feeling, feeling, seeing stories underfoot. She turns, showing how the tourists could experience entrance to the site, not facing the grandeur of the rock, but away from it experiencing the land, then guiding an imaginary path to the entry, she turns toward the rock and sees it for the tourist. “Oh!” she exclaims, then turns her tourist away from the spectacle to enter the building. Tony Tjamawa says, “We have rounded up the stories and have them like horses in a yard for you. Now you are on the inside … draw it, build it!” ›› This is the invitation to enter with care.

A communing is called for. Anangu, the people of the centre, are immersed in their own world. Metaphorically speaking, their countenance is turned away – moving out and sweeping round – their gaze is elsewhere on a spirit-filled cosmos, mediated by stories and beings held in the land, held in the stars. Tjamawa, the elder and lawman, says the knowledge is in the land: it cannot be destroyed – one needs only to listen carefully. The law is there, as it always was and always will be.

Entering into the other’s space, across the culture of the land – across the wounds of dispossession and colonialism – one listens, sensing out resonances, shadows, fleeting openings. With the women we map the site – footsteps making and marking out the features of the ground. We follow the givens of animal track and trace; make neighbourly shifts to accommodate rock and tree, dunal directions; the grandeur of the rock always to our back. We skirt between and around the lie of the land, to make a space in which timeless rituals of figures in a landscape can find a gathering in – a natural gathering up. To commune with the sensitive chaos of the other, one opens one’s senses.

I am listening with my back, my hands, my feet. My bodily space is alert. I am feeling my way.

We move over the land. The ancient dead Desert Oak is gathering a site up around itself – it is a clearing with a story manifesting in its midst. The women move around it, it gathers up. It is marked auspiciously with a grove of tiny desert oak seedlings around the base of the original. Shade can be made. The women have found a Wiltja site: the shade of soul, the shade of the dead, a shade to shelter. Out of that will come a building. The building will not be frontal; its gaze will be elsewhere. It will gather up around the ruin of the great Desert Oak with its promise of renewal. “See with your heart,” says Tjamawa.%br% PRESENCING THE ART OF BECOMING%br% The philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy refers to presence as an arrival – a coming and a birth – not as signifier of a transcendental being.

He writes, “presence is the thing itself, as it comes plastically to the world … it is in itself … all coming to its presence.” ›› What is this “birth to presence” in architecture? We find it firstly in a poetics of materials – of materials given full range of expression, when the radiance of handwork bestows care and creativity on them, when materials are able to give voice to their own primeval origins.

Stone invokes fire and lava or the trace of patient oceans laying down shelly sediment and holding the memory of a dawning solid silence, of forests breathing and dying; of wood engrained with nature’s biography.

Memory, inherent in materials (even when transformed to the outer limits of technology), speaks to us bodily. It is a sensual transmission that not only reminds us of our own organic nature – affirming the deep rhythms of that nature – but, through techne or making, the making of architecture also embodies our culture and our spiritual condition. Natural materials, used culturally – that is, in “making” – are uplifted and transformed from the primeval and become part of humankind’s language. Part of our story. The trend toward surface composition and the theoretical problems of representation (at the expense of form making) can sometimes deprive materials of their full expression; they are made anaemic and drained of vital energies when entirely subservient to abstract impulses. “Truth to materials” is profoundly connected to form making.

Forms also have their primeval origins, not only in the womb of cave and shelter, but essentially and originally in the dynamics of the human body itself. We literally resonate with forms; we take soundings of space – we can feel weight, gravity and mass through our own load bearing limbs and spine. The step and bound of our walk can be projected to encompass and measure space and distance. Our uprightness determines more than our human status. Forms find their origins in the concave and the convex of the infinitely complex folds and structures of the body.

Paul Klee (after Goethe) invokes the “formative forces”, that is, those metamorphosing forms which are, even when built, still in the process of becoming, still in the process of being born to presence. Klee writes, “An artist is more concerned about formative forces than about finished forms.” This infinite becoming, this force toward incarnation in materials and forms, enables us to work deeply into place, to make place – bringing place to presence.%br% SHADOW SHELTER FOR THE SOUL%br% Shadow gathers, dwells, dapples, weaving with light, breaking under scattered cloud or the bough of trees into a thousand dancing pools.

Welling up against walls in thick sheltering silence – retreating under eaves to whisper and remember, like a voice in the recesses of the dark verandah – shadow lies receptive, patient, consoling, waiting for our return, our homecoming.

The silent struggle between light and shadow is everywhere in architecture; its shifting mood through the day and across seasons delights and entrances us, its contrasts and sequencing give spaces emotional range and rhythm.

Goethe talked about colour being the deeds and suffering of light.

Colour arises out of light and is swallowed up again in darkness.

At midday shadow is dense, short, contained and shot through with the sunlight that almost dematerializes the exposed surfaces that create it. Early morning and late afternoon our shadows become ground and feet bound giants stretching impossibly before or behind us. At dawn and dusk all becomes shadow as it drains light, forms and colour of their separateness.

Shadow in Aboriginal understanding is simultaneously shelter, soul and “the dead”, evoking its liminality, its in-betweenness. It is both the shadow within and the shadow we cast.

A sheltering and concealing shadow is a matter of survival under a harshly exposing sky; it is also a matter of internality, the inner concavity where depth, the feminine, the ground of the psyche can gather substance. It is the dark inner ground where remembrance, mourning and the watering of wounds can be attended to. The layering of space with light and shadow reflects the layering of our psyche, offering it retreat, sanctuary and protection.

Places of shadow can engender healing by allowing for mourning, making place sufficiently richly nuanced to act as receptacle of loss and absence: to be a refuge for a strengthening and rejuvenation followed by a re-emergence into the light and the world.

In the final stages of the documentation of Brambuk I was surprised by a realization. Parts of the interior were over-lit; a more cave-like interior was needed (with gently modulated light) to hold and nurture the fragile and damaged folk soul of these communities. Sometimes architecture is asked to express tragedy as well as hope, to support the mourning of loss as well as celebration. From this need, a difficult and poignant beauty can be born.

Offering refuge for the folk soul is not a retreat into primitivism, but a reconstellating of the forms, materials, spaces and energies necessary for healing and human wellbeing at its deepest level. What is brought to surface, to composition, to style (the predominance of the visual sense) may not scratch the surface of the deep physical, emotional and spiritual needs of individuals and communities who have been dislocated; and is that not all of us? In architectural terms, a reinscription of the other senses needs to occur; the mobile body should be readmitted into architectural process.

To reconstellate connectedness one must break the ground, build deeply into materials, into the earth, the body of the earth. As the ritual scarring of warriors’ bodies demonstrates, physical wounds can signify transformation towards the spiritual. The ritually broken ground holds the shadow of healing. As Gottfried Richter enigmatically expresses it in his Art and Human Consciousness, “the place, where the ground breaks open toward the inside, is man himself”.%br% MYSTERY LIVING WITH QUESTIONS%br% There are many dances for exploring the mystery of the unknown space in front of us, and each has its own choreography. Like Dionysus’s ecstatic cohort we can dance over unknown rocky terrain – and not fall – if we are moving under the inspiration of the god. If we can find the courage and faith. This entrancing space is always ahead. We need to allow for its ambiguity, its uncertainty; we can trust to the steps of our dance to carry us across it. It is a space, a ground, we can keep open without pre-emptive conclusion.

Contradiction, ambiguity and paradox become catalysts for living everyday life more authentically, more poetically and with spiritual and imaginative resonance. The space of mystery is the space left open – an imaginative space letting in the unanswerable, the ineffable; a space where we can hold the mystery of human suffering and tragedy as well as an affirming acceptance. Being present to the mystery of the everyday brings the prophetic imagination into our midst.

Unknowing or, as Keats called it, “negative capability” is the natural air of the artist. It is a source of creative tension, of receptiveness, when our deepest questions are kept in play until a right moment, an intuitive alignment and a germination takes place. Maintaining this space against the economic and commercial imperatives of running a practice is an act of courage and faith. But there are rewards in allowing this rich space of arrival. There is also the possibility of enchantment, wonder and mystery gracing our lives.

The young embrace this space, it is their very medium. They can be encouraged to have faith in themselves in the midst of their unknowing: their questions, their dreams will mould the future. In the face of orthodoxies of thinking, and the tyranny of fashion, let them reinvent, intervene and turn inside out their stories and ours, so that they can find their own touchstones, ground a vocation in this place and affirm a home here.

In 1968, a year defined by student-lead social and political upheaval, Louis Mumford framed a discourse for our abiding relationship with our buildings, which still resonates today:

“We are the maker and moulder of [ourselves]. In that process, architecture has been one of the chief means … of transforming and making visible to later generations [our] ideal self … the time has come for architecture to come back to earth and make a new home for [us].”%br%

Gregory Burgess is the RAIA Gold Medallist for 2004. This address was delivered at the University of Melbourne on Friday 16 July, 2004.

ART, COMMUNITY, ENVIRONMENT, SPIRIT

AN APPRECIATION OF GREGORY BURGESS ON THE OCCASION OF THE A. S. HOOK ADDRESS

It is truly an important occasion that Gregory Burgess should be awarded the RAIA Gold Medal and it is an honour and pleasure to be asked to say a few words tonight about what makes his work so special.

Despite the many awards this work has attracted, it is neither large-scale nor particularly prolific. It has often appeared as somewhat marginal to mainstream professional practice, yet with a depth, potency, rigour and relevance that cannot be ignored. One of the things that make these buildings exceptional is that they engage with so many different dimensions of architectural theory and practice at once, and they do this in a manner that is both popular and just a little disturbing. In a sense this is an architecture that may be found on several different cutting edges at once. I suggest four main ones: the aesthetic, social, environmental and spiritual.

At an aesthetic level this work is a celebration of everyday life, an architecture filled with positive desire, an affirmation of the art of architecture as the art of dwelling. While the buildings are often exquisitely beautiful, this is not an aesthetic of contemplation so much as one of engagement, an architecture that at once constructs, represents and shelters us. Greg’s work shows us that the all too common conservatism of architectural taste is often a thin cover for a deep-seated and widespread desire for a more imaginative future. Greg’s work unleashes flows of desire in a manner that is not limited to the taste of a social elite. And in doing so it transgresses one of the golden rules of the avant-garde – it is popular. It is a radical architecture that catches the public imagination.

This is the social dimension. Greg’s work is a social art that engages with difficult conceptions of “community”. “Participatory design” and “community architecture” are phrases that have became clichéd through overuse, demeaned as a cover for manipulation, and stained by association with the banal results they have too often produced. Some years ago, while I was speaking about Greg’s work on talkback radio, a local architect called in to ask: “If Burgess’s work is so participatory why is it that his buildings all share a common style?” The question, for me, betrays the fear that many architects have, that to engage with the social is to surrender the architect’s voice. Greg’s particular achievement here is to demonstrate that “community architecture” need not be common, that the public interest is not served by the lowest common denominator. This work is a testament to the capacity of architecture to raise the bar of community life and to construct new possibilities for social life and collective identity. The architect’s responsibility is broader than that of the fine artist – architecture indeed is a social art.

The environmental dimension of Greg’s work involves a concern to integrate ecological concerns into the central tasks of architecture. In an era when we still give specialist awards for sustainability, as if it were not a necessary part of the art of architecture, Greg’s work celebrates architecture as an ecological art. This is an architecture that becomes sustainable at a level beyond the technical issues of solar orientation, energy transfer and materials, embracing larger concerns about how we live and the values and forms that are worth sustaining.

There is also a more personal, mystical and spiritual dimension to Greg’s work. And here, as in talking about aesthetics, beyond a mundane level words begin to fail or sound pretentious. I will simply say that for me this is not a pure or transcendent spirituality that takes us out of this world, but an everyday spirituality that is of this world; it is the world one sees in the grain of sand, or in this case the building.

I think of Greg as the Michael Leunig of the architecture profession, revealing somewhat difficult truths in a disarming yet potent manner, connecting the local desires of everyday life to a larger condition.

These threads of art, ecology, community and spirit come together in all of Greg’s work and particularly in that undertaken with and for Aboriginal communities where the task of architectural design is fraught with the tensions of national politics, cultural tourism and the struggles of some seriously damaged communities for social justice and reconciliation. These buildings have been the subject of sustained debate, they have been celebrated and for some they have been unsettling. I can recall in the late 90s interviewing members of the Anangu community who were involved in the design of the Uluru – Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre. They loved the building, which they felt they had designed; they had nothing but praise for Greg’s work in bringing their ideas to fruition; but they couldn’t understand why all this recognition of the architecture was not coupled with a broader reconciliation between non-Aboriginal and Aboriginal cultures. Every architect who has worked with disadvantaged communities encounters the dilemma that architecture alone cannot solve entrenched social problems. But this is no excuse for a retreat from the challenge to engage, as Greg’s work does, with issues of cultural difference.

Architecture is both form and process, it can transform ways of seeing, and one of its contributions can be to stimulate desires on which architecture alone can’t deliver.

Greg grew up in Box Hill at a time when that part of Melbourne was socially and architecturally somewhat monocultural – white and lower middle class. Box Hill is also the site of the Community Arts Centre of 1991, a building that breaks with that monoculture, confronts and cuts across prevailing order in a manner that nurtures new expectations and desires. Box Hill is not monocultural any more, and this is an architecture for new becomings, new identities and new communities – it is an architecture that remains ahead of its time.

It is easy to place Greg’s work within the traditions of an organic architecture, which I take to mean an architecture of fluid forms geared to a local ecology. Yet his work has never been a quest for purity of form, and he has never been one to retreat from the complexities of urban life. My main regret about this work is that it has almost always been relatively [nobr]small-scale[/nobr]. “Community” does not have to mean small.

Greg shows an uncommon capacity to bring the community with him in breaking open the potentials of architecture and urbanism, to capture the public imagination for a better future – aesthetically, socially and environmentally. There is no greater demand for such public imagination in Melbourne today than in the design of “activity centres” that are being so fiercely resisted across the suburbs. There is a great deal at stake in this struggle and my hope is to see the potential of Greg’s work expanded into the broader public realm of this great city.

As an academic, trying to analyse the ways in which the best of our architecture is caught up in the contradictions, conundrums and power relations of our era, Greg Burgess is the only architect I have ever been accused of going soft on. If there were any truth in this accusation, it would not be hard to find excuses. This is an architecture with both roots and wings, rooted in this fragile landscape and its often fragile communities, yet also filled with a Dionysian spirit of joy that transgresses the prevailing order and opens a window to new possibilities. His contribution to architecture in this city, this country, this planet has been, and I’m sure will continue to be, immense and profound.%br%

Kim Dovey is Professor of Architecture at the University of Melbourne. Paul Carter, Ian McDougall and Harriet Edquist also presented tributes on the occasion of Gregory Burgess’s A. S. Hook Address.

Photography Credits

Brambuk Living Culture Centre, Trevor Mein; window detail, Greg Burgess. Catholic Theological College, John Gollings. Eltham Library, courtesy of Nillumbik Shire Council.

Hackford House, John Gollings. Windover residence, World of the Platypus, Imperial Austria Exhibition, Greg Burgess. Uluru – Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre interiors, Greg Burgess; interior with snake, Tim Webster; roofscape, Jimmy Yang. Nebula, Galaxy Picture Library.