OWEN AND VOKES EXPLORE THE POTENTIAL OF THE SUBURBAN BACKYARD IN TWO RATHER DIFFERENT OUTDOOR ROOMS, WHICH BOTH EXTEND THE INTERIOR AND GATHER IN THEIR SUBURBAN SURROUNDS.

<b>REVIEW</b> ANTONY MOULIS AND SHEONA THOMSON <b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> JON LINKINS

Front elevation of the Clayfield House. The new gatehouse begins a sequence that culminates in the new outdoor living space at the back of the block.

Front elevation of the Newmarket House.

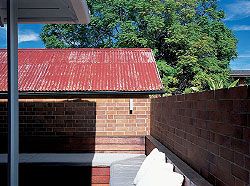

The Clayfield project extends an existing bungalow by architect Mervyn Rylance. The new work occupies most of the backyard and is conceived of as a series of “garden walls” that extend the sensibility of the bungalow.

The Newmarket project extends an Art Deco house with a large living/outdoor terrace, floating on the lush green lawn.

Looking west from the small garden through the deck, with the fireplace chimney in the centre and the dining area to the right. Neighbouring houses and gardens become part of the visual composition through the construction of selected views.

Looking from the deck across the dining area to the living

Built-in seating on the deck, sheltered by the “garden walls”.

Newmarket House. Looking from the kitchen across dining and living areas to the left, and the outdoor room to the right.

View along the length of the outdoor room in the Newmarket House.

THE SUBURBAN BACKYARD might be hidden from the street but it is certainly not out of the public gaze. On what seems like a nightly basis, “reality television” brings the backyard into our collective living room, to both mortify and delight us. Meanwhile, in the world of popular home magazines, photographs that best capture the quality of the rear indoor/outdoor edge present a ubiquitous, though no less compelling, image of what the Australian backyard has become – a place of comfort and repose, rather than that half-forgotten space dedicated to utility that we might remember from our childhoods. While the child’s imagination could happily produce untold charms from the simple pragmatism of the suburban backyard, our national obsession with domestic life has inevitably seen that space devoured. In this sense, the seeds of change are more to do with the rethinking of the domestic interior and less to do with any lack in the backyard itself. From the point of view of architecture, this formerly distinct outdoor space has now firmly entered the domain of the house ›› In two projects, carried out simultaneously for two growing families in suburban Brisbane, Owen and Vokes present a refreshingly multivalent approach to the backyard. Both projects seek to adapt a “pre-modern” spatial typology to a contemporary mode of living, significantly altering existing patterns of public and private space. Interestingly, neither house is a timber Queenslander of the type you might expect in Brisbane. In the Clayfield house Owen and Vokes have extended a timber bungalow, full of character, by the architect Mervyn Rylance, working responsively with its quirks and curiosities. The Newmarket house is Art Deco, and has been revered for that by the current owners. The generic traits of each dwelling have been both constraining and generative, as they rub up against the new place patterns of the respective extensions.

There are similarities and very distinct differences between the works, particularly in the orchestration of the ubiquitous kitchen/living/outdoor nexus within the overall composition. At the Clayfield house, the extension effectively takes up all remaining open space on the rear of block. This space is reinscribed through an architecture of “garden walls” that extends the formal sensibility of the existing house. A gatehouse on the street begins a sequence that culminates deep in the block at the new living/outdoor space. This sequence is developed independently of the existing internal circulation of the house, though the two are connected at the existing front door and entry stairs and again at the rear living space. In bypassing the front stairs, the new sequence to backyard public living allows the internal organization of the house to be reversed – private spaces at the front and public at the back.

At Newmarket, the reorganization of space within the house is also felt in different ways. On entering the property, it is clear that the magnetic space is at the rear of the dwelling – a large living/outdoor terrace – but to gain access to it one must pass through a room that was formerly a living space at the front. Now cleared of that lively function, the front room has become a purer place of prospect over the open garden and the street. Once through the flesh of the existing house, the hyper-real spatial and material purity of the extension is experienced. The whiteness of the frame of the outdoor room, set beyond the “humbled” raw concrete ground of the kitchen/eating/ living space and within the extraordinarily vivid green of the lush grass yard, presents a more generous scale than is suggested by the original house.

Both renovations are part of a broader set of works by Owen and Vokes that consciously address the idea of the new backyard in the context of Brisbane. In these works the formal and spatial game on this indoor/outdoor edge is no longer about a distinct and orderly transition between interior and exterior in the manner of the time-honoured verandah. This conventional inbetween space is now reconceived as an outdoor room that gathers up both interior and exterior within it, only to make the essential line of enclosure (the weather proofing one) recede or disappear. This “room”, cast as inbetween space, is conjured up in the imagination of the occupants out of their visual and sensual reading of the group of elements that surround them inside and outside – walls, openings, floor treatments, ceiling planes et cetera. Seamless transitions across the line of enclosure are critical to such architecture and these two projects offer a compendium of solutions to visual and material transitions at a fine level of detail.

In the suburbs of Brisbane the remaking of the backyard as an open extension of the interior also makes good sense of the benign climate. Yet the image of the Queensland house that we are most familiar with presents the verandah as the archetypical climatic filter, protecting the interior across its depth and harbouring a nest of rooms within. The outdoor room offers a different response, resisting neat or pragmatic distinctions between interior and exterior. It is all about extending and amplifying space rather than parcelling it in a hierarchic manner. Owen and Vokes’ strategy is to describe a larger single room out of walls that frame a space both interior and exterior. The walls of this room are pliable; they may erode, open or close for the purpose of spatial effect. Through this strategy, the scale of domestic living is given added breadth as neighbouring buildings and gardens are visually appropriated into the composition of the whole through the construction of carefully selected views. This obscures the physical property line, drawing in space beyond the owner’s private domain and evoking the suburban surrounds as an interrelated patchwork of rooms. This is particularly evident in the Clayfield house.

By blurring rather than formalizing the indoor/outdoor edge, the outdoor room is determinedly ambiguous in its spatial character. It perhaps recalls another archetype, that of the Roman house, particularly the atrium, with its opening to the sky suggesting a simultaneity of openness and enclosure of the domestic interior. The patterns of relationship in the newly extended contemporary dwellings also call to mind, through the contingent reorganization and reassignment of functions in existing spaces, the relationships in those ancient courtyard houses of the cellular spaces to the open, receptive, adaptive ones (typically ceremonial and demonstrative). When the formerly open spaces of suburban backyards are taken up and into the fabric of the home a very deep territorial axis is made, just as in the houses of Pompeii.

This is a curious thing to ponder, given the often surprising openness of the swathes of continuous yards in our suburbs, punctuated by a range of possible divisions – from low open wire fences to high brick walls. It means we cannot assume any uniform attitude to the densification and active publicizing of the rear of our plots. At Clayfield, the walls are solid, and boundaries are breached by carefully edited appropriation. At Newmarket, the backyards are more flimsily divided. Fences could be jumped and the neighbour’s dog could lunge against the wire, at a child playing on the grass, so the “ruined fragment” of enclosure pulls back from the real property boundary, suggestively containing the newly fashioned, more hedonistic world of space, while respectfully maintaining the contextual status quo.

According to Dutch architect N. J. Habraken, “the distinction between a formal front and a more protected and informal back is very much ingrained in territorial consciousness”. In the patterns of Australian suburbia, a greater intensification and formalization of the space of the back potentially engages what Habraken would call a “horizontal shift in territorial division” (in opposition to “vertical”, the term by which Habraken defines the usual sequence of territorial division; that we typically move “vertically” from most public to most private, from the world of the street, through the various defences and thresholds of the house). While not as extreme as the examples of horizontal redefinition that may be found elsewhere in time and place, the “publicizing” of the space of the rear of blocks does challenge that which we intuit the backyard to be.

In seeking a match between added built forms and a regional sensibility, Owen and Vokes have largely avoided architecture of timber filigree and screen (a tectonic that seems to inevitably stalk domestic architecture in our subtropical clime). By opting for an architecture of walls and by exploring the idea of the outdoor room, the architects find themselves in new territories within the context of an appropriate regional response and there is both subtlety and assuredness in their work. In conversation with the architects on our visit to the houses it was interesting to sense their concern not to entirely erase the patterns of use that had characterized the houses, now so greatly altered in the face of contemporary demands. Strangely, those former patterns seem to remain as remnants in the fabric despite the changes, clearly at odds and yet comfortably so – a reminder of that patient search for a “perfect” domesticity.

ANTONY MOULIS IS HEAD OF ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND. SHEONA THOMSON IS A LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT QUT.

REFERENCE

N. J. Habraken The Structure of the Ordinary(Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1998).

Project Credits - Clayfield House

Architect Owen and Vokes— project team Paul Owen, Stuart Vokes, Aaron Peters. Structural engineer Farr Engineers.

Hydraulic engineer H Design. Builder Mair Renovations.

Project Credits - Newmarket House

Architect Owen and Vokes— project team Paul Owen, Stuart Vokes, Aaron Peters. Structural engineer Farr Engineers.

Hydraulic engineer H Design. Builder Carbines Constructions.