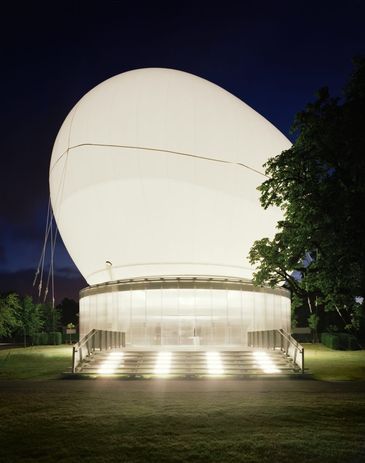

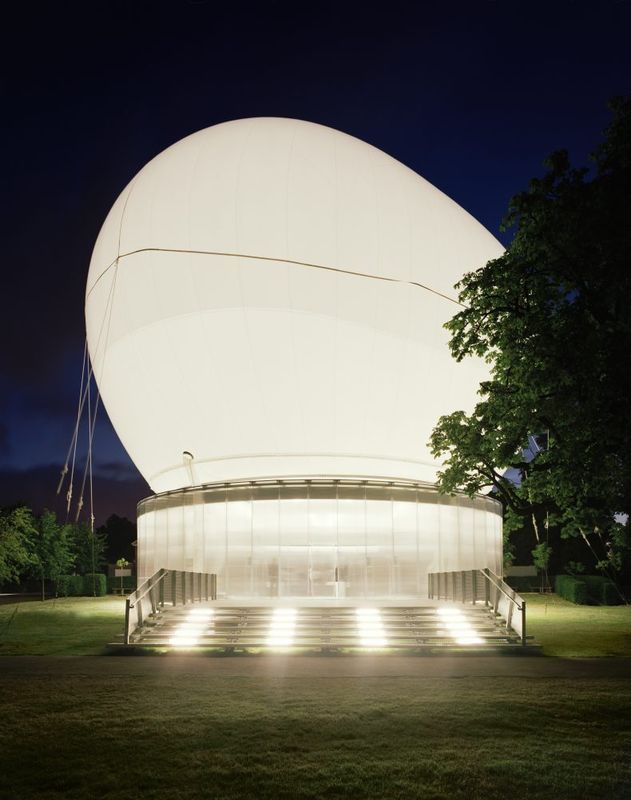

Looking back, we might identify the 2006 Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, by Rem Koolhaas and Cecil Balmond, as the moment when the idea of curating architecture crystallized as a distinct topic. This was when Hans Ulrich Obrist joined the gallery and introduced the 24-hour Interview Marathon program of events that accompanied the pavilion exhibition, co-hosting it with Koolhaas that year. It was clearly a moment when the rise of the professional curator – the auteur curator, in the case of Obrist – collided with a rise in the popularity of exhibiting architecture.

2006 Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, by Rem Koolhaas and Cecil Balmond.

Image: John Offenbach

While there has been much written on transformations in curatorial practice since then, and on the long history and paradoxes of exhibiting architecture, there have been surprisingly few attempts to drill down and better understand what, if anything, might constitute a specialized curatorial practice attached to architecture and design.

This is the territory of Fleur Watson’s book The New Curator: Exhibiting Architecture and Design (Routledge, 2021), which makes a case for curating architecture and design as a specialized activity. To do this, Watson makes links between new concepts in curatorial theory, including curatorial activism and the educational turn, and the notion of expanded practice in architecture, describing the new curator as a figure that “actively seeks to mediate, translate, engage and perform these new forms of expanded design practice in active exchange with audiences” (page 17).

The New Curator by Fleur Watson (Routledge, 2021).

Image: Supplied

Watson’s tactic of personifying the new curator resonates with the contemporary phenomenon of the independent auteur curator, exemplified by Obrist. However, her intent is to leverage the performative potential of the role, rather than play into a curatorial star system or valorize particular identities. As such, the focus of the book is very much on curatorial strategies, or “moves,” and how these might constitute a repertoire or palette for the new curator. Watson elaborates each of these moves through analysis of a series of cases that reveal the range of contexts in which the new curator might operate: inside and outside institutions, for public or private clients, in galleries and found spaces, from the scale of an installation to a biennale. The question of how specific to architecture and design these moves are remains open. The “curator as space-maker,” for example, is highly architectural, while the “curator as interloper” has a wider applicability.

Flores and Prats’ project Liquid Light, for the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale, is used as an example of the “curator as space-maker” and the potential of the full-scale exhibition of buildings or fragments to communicate design ideas. Watson discusses the architects’ work as a logical extension of their architectural practice. Elsewhere, Koolhaas’s Elements of Architecture, for the 2014 biennale, is discussed as an example of the “curator as translator” and the potential of the exhibition to be a platform for research. This example is a useful counterpoint to Flores and Prats’ more modest engagement with the biennale juggernaut, inviting consideration of how these two scales of curatorial practice might interrelate and open up the discipline in different ways.

Liquid Light by Flores and Prats

Image: Flores and Prats

Much like an exhibition, the book is organized as a layered and multidimensional artefact. The case studies are supported by multi-page image spreads with large font captions that mimic museum didactics, while the explanations of the curatorial moves are intercut with a series of conversations between architecture and design curators that provide an engaging and insightful snapshot of the contemporary scene.

While the book seeks clarity on the specificity of curating architecture and design, what emerges from the curated conversations is a sense of its hybridity, and indeed, precarity. Prem Krishnamurthy outright refuses the term curator: “I’m not using the word ‘curator’ right now … I prefer … exhibition maker … I’ve always thought that there’s a strong overlap between the fields of designing, curating, editing, writing or teaching” (page 61). In her conversation with Marina Otero Verzier, Mimi Zeiger prompts us to consider the labour of curating, particularly the “emotional labour” of working as an independent content producer mediating between “the strategic goals of an institution and … an exhibition” (page 201).

Part of the ambition to articulate the specificity of architecture and design curating is to promote the built environment as a unique lens on contemporary global challenges, a sentiment articulated by Otero Verzier: “The world is changing dramatically, and architecture is one of the lenses through which we read and participate in it. Maybe the work of curators is precisely to shed light into the social, political, ecological implications of architecture, and offer strategies and knowledge to take sides and intervene within them” (page 200).

But is it also worth moving past the idea of architecture’s exceptionalism? Although beyond the scope of this book, it is perhaps just as important to make a case for how, through its curation, architecture and design might reverberate within the wider cultural field, and effect a more direct change in how cultural institutions think. This is a question not of the specificity of architecture and design curating, but of the stake of architecture as a part of culture; and an idea of the curator as an operative, not within culture, but upon culture – where value systems can be remade.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 25 Jan 2022

Words:

Susan Holden

Images:

Flores and Prats,

John Offenbach

Issue

Architecture Australia, November 2021