The Piano Mill is a unique architectural structure in a forest on a remote property in south-east Queensland. It’s a homage to the pianos and parlours of outback Australia, and an outrageous mega-musical instrument. Created by architect Bruce Wolfe (managing director of Conrad Gargett) together with composer Erik Griswold and artistic director Vanessa Tomlinson (both from Clocked Out), The Piano Mill also explores the complexity of music performance in curious and wonderful ways.

Music performance is always a complex arrangement of people, place, space and sound, whether in a concert hall or a pub. The Piano Mill takes this to a new level, exploring every aspect of this complexity in a purpose-built site that proposes a new way of making music: a site-specific performance venue, in the bush, using 16 reclaimed pianos relocated in a new building. The launch event, held at sunset on Easter Sunday 2016, brought together 16 piano players alongside the architect, the composer, builders, a chef, volunteers, a dancer, directors, film crews, recording engineers and a community of listeners. Erik Griswold’s 60-minute composition All’s Grist that Comes to the Mill was premiered amid all the variables of weather, solar power, natural sounds and the good will of the newly acquainted participants in the Mill project.

The Piano Mill by Bruce Wolfe features an atrium-like hole allowing access to the pianos.

Image: Marc Treble

The 16 performers were positioned one on each of the pianos, eight on each level of the two-storeyed copper-clad building. The structure rises on stilts from ground level, pushing into the canopy of the surrounding eucalypts. Pianists were perched (literally) at these pianos, many of them staff of Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University, as well as others from further afield, alongside a percussionist/director – Michael Askill and Vanessa Tomlinson – on both levels, and the composer himself. The performance included a movement artist, Jan Baker-Finch, raucously winched down through the atrium of the Mill to open the proceedings. She was also charged with opening and closing the louvres on each wall to alter the intimacy of the sound world, and to participate as a part-time conductor by turning lights on and off.

Video artists Greg and Emma Harm projected onto the copper-clad external walls of the Mill as darkness fell. They used real-time filming from inside the Mill to project the secret inner workings of the building onto the outside of the structure. What was invisible became visible, what was only known to the performers was revealed to the audience, and the operating of the Mill machinery became a little more comprehensible. Large white umbrellas, purchased in case of rain, were held by audience members to catch the overflow of the projected images. Carefully laid fern fronds underneath the Mill gave pops of bright green among the deep copper colours of sunset on the structure, contrasting tantalizingly with the cobalt blue and black clothes worn by the performers.

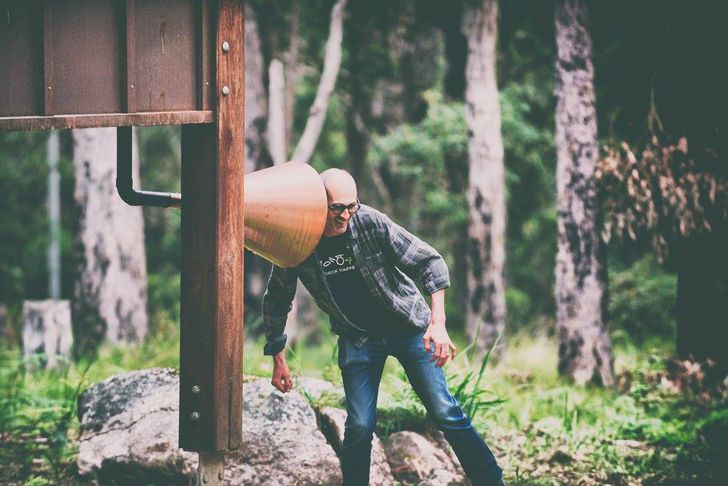

Two purpose-built copper megaphones protruding from the bottom of the Mill highlighted particular sounds from certain pianos.

Image: Tangible Media

Two purpose-built copper megaphones protruding from the bottom of the Mill highlighted particular sounds from certain pianos, and audience members could choose to move around to explore these different listening vantage points, or to remain stationary. The building itself was in sonic flux through the opening and closing of louvres, and the selective amplification of the megaphones, and in visual flux through the setting sun, lighting changes in the building, and the projections. And in environmental flux through mist, rain, bird life, insect buzz and audience whispers.

To complete the multi-layered scene, recording engineer Myles Mumford was perched in an impossible corner inside the Mill, listening to his microphones set up both inside and out to capture the full effect. A second film crew from ABC were also documenting the project in 360 surround-vision inside the Mill, with cameras hung and hidden in various positions.

Audience members gathered throughout the day, bringing folding chairs and picnic dinners – those that arrived early could indulge in a full day of sonic activities, others came just in time for the grand entrance of the Mill performers (the performers disappeared under the Mill in ceremonious procession to ascend a ladder into the structure). Volunteers handed out programs, chatting about the project, as the chefs in the kitchen prepared a well-earned meal for the performers.

Notable in this project is that no single person had the role of executive producer. Instead, each person in the collaboration had a specific job which interacted with others. Surprising things happened: the accompanying hum of a generator as the challenge of a solar-powered production at the end of a misty afternoon was realized; and the fireworks at the end that the neighbours had secretly planned. This project was a jigsaw puzzle with no picture - each individual doing their best to make the Mill run smoothly.

Pianists inside The Piano Mill.

Image: Greg Harm

The back story

The beginnings of the Piano Mill lie in the discovery by Bruce Wolfe, in researching his architectural thesis in 1975, that there was a time around the end of the 19th century when Australia possessed more pianos per head of population than any other country. Many of these reached the outback by camel and bullock dray, undoubtedly in not perfect condition. Whether this was hard fact or partly a myth no longer matters, because it lodged securely enough in Wolfe’s memory to be reignited on meeting composer Erik Griswold who often works with prepared pianos. Wolfe thought of all those decaying pianos around Australia pre-preparing themselves to be written for by Erik. And the Piano Mill project was born.

During performances, The Piano Mill is in sonic flux through the opening and closing of louvres.

Image: Tangible Media

The two-storeyed Mill was designed around a floor plate of about 4.5 metres, allowing 2 standard upright pianos against each wall on each level, so altogether there was room for 16 pianos. The building was raised off the ground to allow the pianos to be hoisted through an atrium-like hole in the middle of the building into their new home. The large louvres on the walls were designed to be opened and shut to alter the Mill’s acoustic. The 16 pianos were sourced from local areas; many quite serviceable, and even reasonably in tune, and others more dilapidated, with wonky keys, weathered timbers, and unmelodious tones. Wolfe’s concept was that the pianos be kept in the original, ‘found’ state to evoke the weathered sound of the outback and a sense of nostalgia.

In collaboration with Wolfe, Griswold created a new concert-length work to launch the Piano Mill, exploring the unprecedented sound potential of this new mega-instrument. Incorporating mass sound textures, nature-inspired soundscapes, and nostalgic fragments of parlour music, Griswold extended his large body of piano works, responding to the architecture, the natural environment, the decaying pianos and the transformative qualities of memory. The collection of movements that comprise All’s Grist that Comes to the Mill makes sense of the decaying mechanisms in unique ways, highlighting the idiosyncrasies of the instruments, microtonal differences, and broken strings. It’s a piece that carries a powerful sense of the story behind each piano.

The ongoing story

We engage with a place in a multitude of ways, through all the senses. Musically, we are all an extension of a place where meanings and feelings are ecologically derived and socially and ritually embedded1. Since the launch last year, the Piano Mill has occupied such a place in a growing community of people. It’s grown to be a place brimming with an inner life and evoking any number of levels of sensual engagement, becoming a home of place-inspired music and art.

Performers climbing ladders up the atrium-like hole inside The Piano Mill.

Image: Greg Harm

Site-specific art – something that is equally defined by its location and by its creator, and permanently in situ – has a long tradition and its many forms have been documented in countless media and publications. Through the ages, site-specific art has been integral to how we experience, connect with and remember a place, whether through the built or natural environment. However, contemporary forms of site-specific art are evolving experimentally, in unique ways. These sorts of forms emerged in the late 1960s as a result of the growing commodification of art and aimed to celebrate the autonomy and universality of art2. This has resulted in a great merging of forms such as land art, process art, performance art, installation art, community-based art, public art, and multi-art forms. Underlying these terminologies is often an integrity that is expressed as the inseparability of the work and its context. In this approach, according to Kwon, there is also a presumption of ‘unrepeatability’ - you have to be there!

While ongoing Piano Mill projects involve new and experimental music and art forms, they also reflect and revive old ways of music-making and production. From the Middle Ages, composers were very aware of the effect of the surroundings on their music and they shaped their music accordingly. Even whether the music of a region is melodic or rhythmic depends, to a certain extent, on whether the people were ‘housed or unhoused, dwelling in reed huts or in tents, in houses of wood or stone, in houses or temples high vaulted or low roofed, of heavy furnishings or light’3 . But with developments in concert hall design and acoustic technologies, relationships between architecture and music, and architect and composer, are to some extent lost.

There are other issues at stake here: while the evolving architectural designs of concert halls provide acoustically detailed listening environments, they fail to take into account the social role of live music. Bentley remarks that the idea of halls favouring straight rows of seating facing a stage is inimical to the sociality of live music ‘of being one of many involved in a special experience’ 4. I would add that such spaces may also diminish the ambience of the experience for the listener and therefore fail to leave an impression, a memory; especially if the music heard in this context is not familiar.

Pianists inside The Piano Mill.

Image: Greg Harm

‘New music’ faces this problem: it is unfamiliar, its diverse composition styles, its expanded pool of instrumentations and its multidimensional forms make it difficult for it to be part of an enduring heritage. It has no home. Performed in concert halls, it can seem out of place. So, while architecture and acoustic properties of spaces have fundamentally influenced types of music that have developed over centuries, this is no longer central to composing and the resulting concert experience. In attending new music performances, audiences face experiencing music that was not necessarily composed for those spaces; and composers face composing music for unknown performance acoustics.

What if we take the composer, the architect, the performers and the audience out of this paradoxical situation and allow the music and its place to grow together? The Piano Mill has offered this opportunity. An ongoing consultative process between architect, composer, artistic director, and the local community in the making of a performance ensures a uniqueness about every event. More than this, because of the rural setting of the Piano Mill, we can observe the impact of environment, landscape and weather on ideas, artistic practices, and performance, as well as on audience.

Some of the premises on which the Piano Mill project was built were:

- the site itself has significance and bearing, and that place informs creativity;

- experimentation removes the kinds of preconceptions placed on performance and performers in traditional venues;

- risk plays a higher than usual role in performance success and audience appreciation and adds a palpable level of excitement not necessarily felt in traditional performance contexts;

- audience members can discover their own ways of listening, unrestrained by walls and traditional seating;

- music, environment and architecture are interrelated in their contribution to sustainable musical practices, and on collective memories. Music grown in a particular place, of a particular place helps to build not only music communities but also a common heritage.

The performance also included lighting projections.

Image: Marc Treble

The Piano Mill and future on-site projects therefore also enable a broader investigation into music and communities. These investigations have, understandably, been looking for models and factors that characterise successful community music ventures. Of no less importance, though, is the very uniqueness of each community or region, perhaps defying a model. Uniqueness is a powerful tool. Activated by wonderment and with the capacity to intensify emotions, uniqueness compels people to share an experience, making it part of a collective memory. Making new music old.

Creative team of the Piano Mill: Bruce Wolfe (architect), Erik Griswold (composer, co-artistic director), Vanessa Tomlinson (co-artistic director)

Performers: Michael Askill, Briely Cutting, Louise Denson, Stephen Emmerson, Anna Grinberg, Erik Griswold, Michael Hannan, Lynette Lancini, Sonya Lifschitz, Therese Milanovic, Steve Newcomb, Alistair Noble, Colin Noble, Vanessa Tomlinson, Cara Tran, Yitzhak Yedid

Movement artist: Jan Baker-Finch

Recording engineer: Myles Mumford

Video artists: Tangible Media

360 visuals: Tim Leslie (ABC Digital Storytelling)

Research: Jocelyn Wolfe

This article was republished with permission from the Asutralian Music Centre’s online magazine Resonate. Read the original article here.

The Piano Mill by Conrad Gargett received a regional commendation at the 2017 Darling Downs West Moreton Architecture Awards on 31 March.

1) Leavitt, J. (1996) ‘Meaning and feeling in the anthropology of emotions’. American Ethnologist, 23, 514-539. DOI: 10.1525/ae.1996.23.3.02a00040

2) Kwon, M. (2004) One place after another: Site-specific art and location identity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

3) Forsyth, M. (1985). Buildings for music: The Architect, the musician, and the listener from the seventeenth century to the present day. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

4) Bentley, D. (2009) ‘New Music: Is anybody out there?’ Music Forum, 15/3 May-July 2009, 17-19.