Paul Keating’s Disneyheadland dominated proceedings at the public presentation of the Barangaroo scheme, with the former PM using his opening remarks to justify the creation of an artificial headland park at the northern end of the site, and then spent the rest of his time being curiously defensive about the Barangaroo Authority’s choice not to go forward with the competition-winning team, with particular attention given to Philip Thalis.

Keating makes a case for the reshaping of the edge of the site, rescuing it from what he calls “industrial vandalism” and culminating in a “natural” headland that will complete the ring of Balls Head, Ballast Point and Blues Point with Goat Island at the centre. Curiously, the fact that this headland will be used to house a car park beneath was not mentioned during Keating’s presentation.

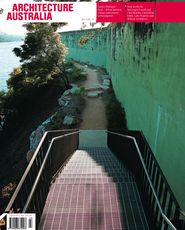

The preferred scheme by Lend Lease and Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.

Beside the bombast of Keating, the presentations by the architects bordered on the banal. Richard Rogers gave a short talk about cities that he likes (out of all modern cities he likes Sydney “the most”) and Ivan Harbour ran through the less contentious parts of the proposal, concentrating on the ground-level public space while ignoring the towers and hotel.

The question-and-answer session was revealing. MC Tony Jones made an attempt at robust debate. To his question regarding the inalienable public land of the foreshore, Keating responded with, “It is a clumsy way to make public space,” and stated that using streets to delineate public ownership of space “is fundamentally a dull, naff idea” – the crowd laughed on cue. However, questions from the floor primarily focused on details of traffic movement, noise and the public art program.

The architects were largely quiet, with the exception of Brian Zulaikha, who asked for more detail on the hotel and another question calling for a finer grain than that found in the urbanism created by large-floor-plate buildings.

Being Sydney, the final question of the night was from a resident of King Street Wharf, asking whether the panel thought the development would lead to an increase or decrease in their property value. It does highlight the primary driving force behind this proposal, which is not the urban form and masterplanning, but the spreadsheets that bankroll them.

The questions that were not asked are crucial. What is the nature of the deal between the state and the developer? What are the implications for the city when one developer is given such a large chunk of real estate? Yes, the details of the deal will be made public in time, but with the contract signed on the day of the public meeting, this information will be of hardly any use other than as historical record.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 2 May 2010

Words:

Marcus Trimble

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2010