Review Sam Spurr

Photography Simon Wood

Looking down into the cavern below the entry pavilion at the Macquarie University underground station.

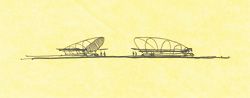

Concept sketch. Two shell-like pavilions face one another.

View down the long tunnel of the unpaid concourse at Macquarie University Station.

The platforms and smaller paid concourse above. This juts over the platforms, with escalators on either side.

The entry pavilions, at ground level, provide the external public face of the underground stations. Macquarie University Station is shown here.

Train platform at Macquarie University Station. The lozenge shape of the underground spaces is an outcome of the process of mining through Sydney’s sandstone.

Subterranean urbanism is a kind of interiority alien to Australian cities – we tend to celebrate the open air, the view, the sunshine. In Sydney this emphasis is even more acute. With our temperate climate, we have little need for the vast controlled environments found in many parts of the world, which have spawned a variety of inventive architectural approaches to making public spaces more habitable. Above the city, skywalks float, cocooning bodies from the cold, heat or pollution. Meanwhile, the surface below is carved up for transportation and shopping malls. The underground stations and linking pedestrian networks beneath a city like Tokyo have the same expansive ambition as Buckminster Fuller’s Dome over Manhattan project – only inverted.

As noted by Ben Hewett in response to last year’s Australian Institute of Architects conference, the privileging of the section in this country over the last twenty-five years has cultivated an emphasis on external form. While the section has the ability to reveal and explore the relationship between the inside and the outside, too often it has simply led to a focus on building shape – cantilevered angles, dramatic roof lines. The interest is in how a structure sits in the landscape and against the sky, its poetic capacity to “touch the earth lightly”. However, this dedication to the exterior is at the expense of both volume and interiority.

Underground environments necessarily privilege the shaping of space rather than the form of it. Carving, cutting and mining become the strategies for creation. In the case of the new Epping to Chatswood underground stations, the act of volume making is tangible. In contrast to Hassell’s Olympic Park Station, whose architecture literally embraces the sky and surrounding context, these new stations are sunk deep in the earth. The arching caverns of the entrance spaces leading into different transition zones describe the process of tunnelling through the Hawkesbury sandstone.

In the Epping to Chatswood Rail Link, Hassell has added another impressive and iconic urban project to its portfolio. Through it the practice has proved again its prowess in strategic, integrated city developments.

The modest brief by the Transport Infrastructure Development Corp was to create “the next generation of transportation excellence” – a comment that would draw many a snide remark from the disenchanted Sydney populace. It is worth remembering that one of the most abiding icons of the industrial age was the grand entrance of the train, smoke pluming, crowds applauding, entering the open platform. It represented a new age where the public could move cheaply and easily across city and country. Futurist cinema portrayed urban mobility in hyper speed – flying pods and literal bullet trains.

Far away from such fantasies, environments for public transport in Australia engage the conventional local typology and are functional at best. Despite the ever-growing need for such facilities, the focus seems to remain clearly on car travel. The new Hassell rail link comes as a welcome surprise in this depressing context – here the drama of train travel is framed and carefully conceived.

To the relief of Sydney commuters, head architect Ross de la Motte describes the central issue of the design as dealing with people, “the whole approach is to make the passenger experience more pleasurable and memorable”. De la Motte has achieved this through dramatic architectural interior and finishes, careful consideration of how people move and flow through the spaces and a commitment to a well-ventilated environment with as much natural light as possible. Rather than seeing the event of public transport as purely utilitarian, they have seen the possibility to make it not only easier but also more enjoyable.

The exterior building footprint is intentionally minimal, but the structures themselves lack aesthetic clout. Their form is derived by continuing the elliptical interior up and out. However, the effect is spoiled by the addition of a winged awning. The most interesting architecture happens underground. The stations were created through a bottom-up approach, which allowed excavation only from the station openings. This resulted in minimal impact on the street throughout the construction process. The entrances to the station protrude like the tips of icebergs above the surface. The translucency of these objects allows natural light to be ciphered down the escalator and lift voids and into the depths of the stations. The glazed skin is reminiscent of fish scales that are “designed to breathe”, a cunning ventilation system whereby the velocity of the incoming train sucks and then blows air through the linked public zones. This frees the stations from airconditioning, creating a constant and relative temperature.

From the entrance, the escalators plunge twenty metres down into the main concourse. This dynamic vertical circulation is heightened by the glass lift that glides between these spaces. The view from either machine is overtly theatrical, and the mirroring effect of the scissoring escalators reflecting the light streaming through the entrance stations is spectacular. Once underground there is a clear choreography of movement for people entering and exiting the stations. This is based on spatial cues and logical intuition rather than relying simply on signage. Based on a pragmatic understanding of user behaviour, the spaces expand and contract, drawing people through the areas in an easy manner. The volumes of the interior concourses are lozenge-shaped, a form derived from the mining process through the sandstone. The effect of these large, curvaceous spaces is both particular to Sydney and stunning.

While de la Motte describes the stations as “modest suburban facilities”, the quality of finishes and detailing proclaim a sense of style and sophistication as well as a long life span.

It is in the quotidian events of urban life that one can begin to judge the success of a city. Australian architecture needs to let go of its nostalgia for the bush and the beach, and recognize the importance of putting design excellence into the daily experiences of city dwellers. We can only hope that this is the beginning of a better standard not only for our public transport environments, but also for the design of our public spaces in general.

Dr Samantha Spurr is a lecturer in architecture at the University of Technology, Sydney.

EPPING TO CHATSWOOD RAIL LINK (ECRL), SYDNEY

Architect

Hassell—project team Pip Bowling, Sally Brown, Kevin Carrucan, Troy Cook, Geoff Crowe, Ross de la Motte, John de Manincor, Hannah Galloway, Brady Gibbons, Mal Graham, Chris Harrhy, David Howe, Luke Johnson, Adrian Lindon, Ken Maher, Des Marsh, John Minnikin, John Morris, Catriona O’Dowd, Grace Pelle-Lalli, Brett Pollard, Tony Rastrick, Matthew Sales, Jari Seppanen, Dario Spralja, Andrew Tatterstall, Suzanne Thomson, Rodney Uren, Amy Watkins, Yan Wong, Mike Wood, Ewen Wright, Catherine Young

Civil and systems contract

Thiess Hochtief Joint Venture.

Station fitout contract

AW Edwards.

Contract manager

Bovis LendLease.

Structural and civil engineer

Opus International.

Mechanical and electrical engineer

Lincolne Scott.

Hydraulic and fire services engineer

Acor.

Lighting

Lincolne Scott (Vision), Point of View.

Acoustic, traffic, transport, safety, risk, facade and vertical transport consultant

Arup.

Quantity surveyor and cost planner

Rider Levett Bucknall.

Fire engineer, pedestrian modelling

Stephen Grubits and Associates.

Accessible design

Accessibility Solutions.

Signage and wayfinding

Emery Frost, Hermes Identity.

BCA consultant

Building Safety Services.