Approached from Lonsdale Street, the project appears as a complex of smaller buildings.

The tower, with articulated lift tower and the glazed pavilion housing the Urban Table beneath.

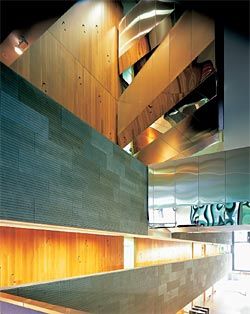

Looking down the foyer to the Lonsdale Street entrance. The foyer traces an old laneway on its ground plane patterning, spelling out the words “Little Leichardt St”.

Detail of the upper level stairs.

The foyer seen from the Lonsdale Street entrance, with glass vitrines containing material from the archaeological dig on the site, and objects by artist Rosslynd Piggott.

The Urban Workshop provides civic space within a commercial programme. Little Lonsdale Street entrance. The canted mirror reflects the Oddfellows Hotel building to the right.

The bridge over the new Madame Brussels Laneway.

Overview of the courtyard.

Lonsdale Street entry with the Urban Table, which aims to encourage street activity.

Twilight view from Lonsdale Street, showing the cranked north-eastern facade.

The city is a notoriously unstable phenomenon and, in a way, we prize its alterity: its largeness, its excess, its dynamic mutability. There are those now in architectural circles who imagine the metropolis as a shifting network of force and data. This is not a new insight.1 However, they now imagine a city made in the image of nature, and seek new forms derived from the disciplines of geography, topography and biology, or that curious hybrid beast biocybernetics. If we remember the city as an image of culture and ponder the force of memory, do we fail the litmus test of currency?

Nature and culture are not mutually exclusive, and memory is a force acting on design through regulatory planning and architectural interest. The Urban Workshop at 50 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne, is partly determined by the data of cultural and architectural memory. It presents various histories of the city and the tower type in a compressed space, where numerous historical moments jostle within the space of the present.

This project occupies quite a narrow allotment on a former car park. It runs north/south between Lonsdale and Little Lonsdale Streets, with the rear part of the building exposed to the north. Located near the upper end of the city, the site is close to Spring Street, a grand boulevard of significant nineteenth-century buildings such as Parliament House, the Treasury, the Princess Theatre and the Windsor Hotel. However, The Urban Workshop sits in a quiet zone, something of a metropolitan backwater. Here the cafes routinely close at 4 pm. Fortunately this deprivation has not deterred the architects’ urban ambitions.

On approaching 50 Lonsdale Street it seems that we are walking towards a collection of buildings: two slender towers (in fact, one building zoned into lift core/car park and office floor plate) and a small nineteenth-century hotel flanked by two louvred glass pavilions. These apparently separate objects are physically joined. Using an approach favoured by a number of recent design projects in central Melbourne – Federation Square, Melbourne Central and QV – The Urban Workshop presents a miniature urbanism. All of these works defuse the singular object/block development in favour of a constellation of forms.2

Multiplicity rather than singularity dominates The Urban Workshop’s interior. Passing into the foyer we engage with numerous material artefacts, carefully arranged in glass vitrines. Many of the pieces are fragments – shards of willow pattern ware, the curved china handle of a chamber pot and cracked buttons, for example. Some of these objects are nineteenth-century rubbish, retrieved from the site’s cesspits during an extensive archaeological dig conducted prior to construction. From cesspit to museum cabinet is an amusing transformation: detritus from the building’s ground plane becomes history’s hard data. In some cabinets, mass-produced nineteenth-century objects mingle with contemporary pieces designed by Melbourne artist Rosslynd Piggott. Such careful curation of the site’s history offers an allegory for the project itself – it is a kind of giant vitrine. Transparent glass walls contain a foyer of collectables: fields of commissioned over-scaled furniture, volumetric carved walls, ceiling coffering and glass display cabinets. The building has highly organized systems of display.

This sense of the project as a collection of things – artefacts and buildings – reinforces the notion of an urbanism in miniature. In recent contemporary Melbourne CBD work, architects have relied on a number of strategies: diverse forms and scales, entrances, passageways and diminutive streets cutting through sites. Constellations of things signify and simulate an image or quality of “cityness”. This urbanism defines the metropolis as a scale of physical differences: large/small, old/new, interior/exterior, passage/stasis and history/ contemporaneity.

Is this urbanism made in remembrance of apparent loss? In the postwar period Melbourne’s central business district was re-fashioned through the construction of large corporate headquarters and office blocks and the relocation of industry to the city’s suburban periphery. Human presence declined with the rise of nine-to-five commuters and fewer city residents. Later, big block developments produced singular, internalized architectural objects. We have tended to see this as the death of the city, although, in fact, it was a mutation of location. This sense of loss is significant and drives the production of contemporary memory. We remember an urbanism that apparently deurbanizes, and we vow not to forget this history.

Like other recent developments The Urban Workshop instigates a network of smaller passages. It registers street morphology literally, in the scale and distribution of the building across the site, creating a traversable foyer and an adjacent laneway to the east, and traces a now-erased thoroughfare into the foyer’s ground plane, signalling the ghost of the site through a change of materials. In the nineteenth century Melbourne’s arcades developed as smaller areas for traffic and commerce (and the lanes for waste disposal and more illicit activities) amongst the larger grid plan. The Urban Workshop, like other recent designs, does more than just reinscribe its site’s history; rather, it pursues a design methodology developed in recent times.

Laneway typology has become the sign of an urbanism premised on the city’s history, using one particular fragment of the nineteenth-century city. The lane delivers in plan (through its smaller scale) and through its function as a passageway for those of us seeking a visible culture of congestion. Urbanism is figured as a certain density of bodies and activities and the movement of those bodies in space. The city is defined as a circulation network. But in defining it so, we wilfully choose a certain feature of the nineteenth-century city. This selection offers an insight into present-day concerns rather than creating historical continuity. In perceiving the past we look through a contemporary lens, not seeing what lies outside the chosen frame. Here, memory rather than historical documentation is at play.

The lane shapes the interests of commerce and determines a certain definition of the urban. Like the nineteenth-century arcade, our new lanes foster certain contemporary commercial imperatives. They harbour intimate spaces for small retail tenancies and promote foot traffic for bars and restaurants. The current use of lanes signifies a recent redefinition of public space towards passages, building proximities and the spaces between buildings. In remembering passages, designers imagine a network of passing bodies as a sign of public life. Buildings are not only shaped for their clients and daily workers, but also for temporary visitors and passers-by. By enlarging their sense of potential inhabitants of space, architects also enlarge their aspirations for the public as a political realm and for the city as a public space.

The Urban Workshop skilfully provides a “civic” space with a commercial programme. It activates the building’s perimeters on the east and north sides through retail tenancies, extending the hours of the building’s occupancy beyond nightfall. On the north side, a lovely modernist canopy creates an intimate plaza space, fostering a strong sense of enclosure and spatial definition. The project patches together the motley collection of nineteenth-century buildings at the rear of the site, successfully managing the transition of scale. It collects the objects around it, generally very well. The fixing of planar glass panels to the Oddfellows Hotel on the building’s front entrance offers an awkward conjunction, but it is a philosophically interesting moment, suggesting the boundaries we draw so strongly around things to transform them from present life into historical artefact.

This project, a kind of machine for accumulating data, also extends its reach to the history of architecture. The building form is generated from another kind of memory – histories of the urban tower and its methodologies and problems. It traces these out by thinking of the relationship between the tower and the presence of the ground plane. As we all know, the tower’s extreme verticality can exert undue pressure on the surrounding space through down draught and overshadowing. The tower’s relationship to the ground is problematic. At the threshold between building and ground, wind forces can deter human habitation of any potential public spaces created around the edge of the tower. Over time numerous solutions to managing the transition to ground and street were invented (plaza, podium, continuity of curtain wall to the ground plane) but these have never seemed quite effectual – each promised to solve a problem but created others. The Urban Workshop traces out these possible compositional and urban effects.

Externally and internally, the project contains a surprising number of remnants of different solutions to the tower problem. Although developed over time, they are presented here as a kind of compressed moment. On approach the building presents a split podium, with the two louvred, glass modernist pavilions flanking the nineteenth-century hotel adjacent to the entry foyer. All three buildings possess the same kind of volumetric size, reinforcing the sense that they might all be a podium. On the western pavilion, a wide concrete ledge survives as a kind of homage to the podium or plaza, since it is occupiable as a seat. The eastern pavilion appears to begin to fold over its little historical neighbour. In front of the entrance, a minimal street setback produces a kind of tiny plaza. The front curtain-wall tower survives all the way down to the street above the entry foyer. This array of possibilities is extended by others offered within the foyer and on the building’s northern edge.

At the rear of the project, on the Little Lonsdale Street frontage, a semblance of an undercroft appears and the form continues into the foyer. On the north-western edge the glass curtain wall comes down, poised to meet the ground only to fold up into a bulky canopy/building form. Here the building cites a contemporary architectural strategy of gathering the ground into the building, where folds, deformations and creases produce design as topographical planes and forces.

In the foyer, the internal continuity/discontinuity of the tower form continues. And many solutions vie here: a residual atrium (with bridge), an undercroft, glass-gridded walls which stop short at first-floor level, the suggestion of a split podium in the form of walls that turn into pavilions. The foyer is busy with design solution and memory. This density of activity and ideas may not be to everyone’s taste, but in its sheer ambition and volume of strategies it sits with work by other Melbourne firms like Ashton Raggatt McDougall. In the image of cityness, we prize excess.

In being so determinedly ambitious the project, like the city itself, ebbs and flows in a drama of success. The Urban Workshop evinces extraordinary attention to detail, control over finishes and ambitious design possibilities in a commercial environment. It does not solve every problem it poses, a trait common to almost every building and every design project, shaped and undone by the capacities of human attention and capital. It is a fine addition to recent work in the city of Melbourne.

Karen Burns is an architectural theorist and historian. With her son Kit, she lives very happily in a John Wardle Architects-designed residential tower in central Melbourne.

Images: Shannon McGrath

1. See Michel Foucault Power/Knowledge, Discipline and Punish and the collected essays in Zone 1/2 (1986).

2. Perhaps this is one of the few places in contemporary Australian cities where architects can work at the scale of urban design.

Credits

- Project

- Urban Workshop

- Architect

- Wardle

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- John Wardle, Paul Katsieris, Lyndon Hayward, Roger Nelson, John Wardle, Paul Katsieris, Stefan Mee, Andrew Wong, Paul Evans, Andy Gentry, Tim Walpole-Walsh, Fiona Dunin, Anna Muller, Derek Hawkes, Sandy Abrahams, Tony Antonio, Ben Albury, Kevin Begg, Phil Bowen, Bernadette Cahill, Paul Conrad, Bob Gant, Sebastian Giacchi, Adam Hannon, Toby Horrocks, Minh Huynh, Michael Hyrsomallis, Emma Jackson, Claudia Monazewska, Luciano Palma, Oscar Paolone, Bronwyn Pratt, Ben Puddy, Grant Roberts, Wayne Sanderson, Antonietta Sofia, Ben Smart, Elliet Spring, Toofan Toghani, Andrea Veccia-Scavalli

- Architect

- Hassell

Australia

- Architect

- NH Architecture

- Consultants

-

Acoustic engineer

Marshall Day Acoustics

Archaeology Godden Mackay Logan

Builder Multiplex Constructions

Building surveyor McKenzie Group

Disability consultant Morris Goding Access Consulting

ESD Advanced Environmental Concepts

Geotechnical consultants Golders and Associates

Heritage consultant Heritage Alliance

Land surveyor Madigan Surveyors

Landscape consultant Sinatra Murphy

Leasing consultant Knight Frank

Legal consultant Holding Redlich

Mechanical and fire services CJ Arms & Associates

Project manager Clifton Coney Group

Quantity surveyor Rider Hunt

Signage consultant Cornwell Design

Specialist lighting NDY Light

Structural and facade consultant Connell Mott MacDonald

Tenant researcher DEGW

Town planning Urbis

Traffic consultant Cardno Grogan Richards (Vic)

Waste management consultant McCartney Taylor Dimitroff

Wind engineer MEL Consultants

- Site Details

-

Location

Lonsdale Street,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

- Client

-

Client name

Industry Superannuation Development Trust (The Urban Workshop)