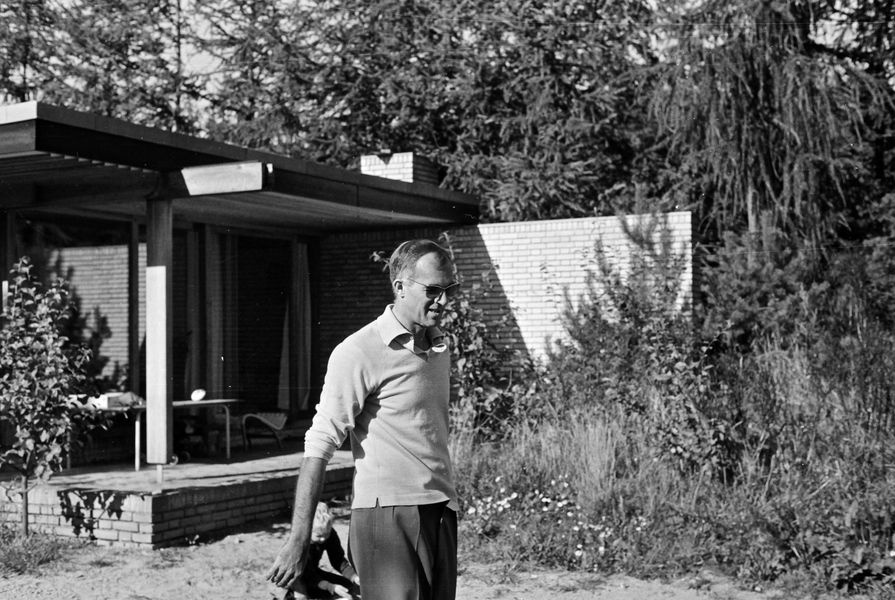

Jørn Utzon, architect of the Sydney Opera House, is an enigma. A recent exhibition, documenting his immediate post-World War Two travels in Morocco in 1947, and two years later, in America, revealed the inspiration for key design ideas that propelled him a decade later from architectural obscurity in a beech forest on the north coast of the Danish island of Zealand to world renown.

Jørn Utzon skiing in Norway.

Image: Courtesy Utzon Centre

The end of the World War Two liberated Danes intellectually. Paris beckoned: existentialism, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir were making headlines; art galleries has been freed from Nazi censorship and were displaying challenging new works. Travel served as an antidote to Danish insularity. Utzon jumped at the opportunity to visit Paris and meet Swiss-born Modernist Le Corbusier. Paris was just a beginning – North Africa and America beckoned. Encounters with Frank Lloyd Wright and Eero Saarinen, Pueblo structures, the desert landscapes of New Mexico, and Mayan temple monuments in the jungles of the Yucatán Peninsula proved transformative.

In the Yucatán, Arizona and Morocco, Utzon discovered the new concept of “Living Architecture,” which harnessed the vitality of sculpture and additional understanding of architecture’s relationship to landscape, such that, instead of architecture being separate from landscape, it should itself be a form of landscape. In many early civilizations, temples were separate and stood apart from and above their surroundings in an isolated, sacred realm. This divorce of buildings from their settings was overturned and jettisoned by Utzon, along with the isolation of landscape from culture.

Utzon gained far more from Alvar Aalto than his short six-week stay in the master’s Helsinki studio might suggest. Aalto was influenced by his surveyor father: surveyors record the disposition of land, not only boundaries necessary for legal title, but its shape, reduced to contours. Where Aalto followed contours and used it to guide his placement of buildings, Utzon went further. Often, we notice Aalto extending the formal order of a buildings by angular terraces that repeat and echo the organic order in his architecture. Utzon built on this idea by making his designs spill outwards over the adjacent terrain, reversing the outward movement and pulling nature inward by transforming his platforms into an a new shaped terrain that was, in effect, treating his buildings as a form of terrain so they are strongly identified with their landscape.

In his work, buildings were not meant to be perceived as alien monuments. Instead, they became extensions of the terrain, albeit a terrain shaped to human ends.

Utzon’s photograph from Morocco, 1947.

Image: Jørn Utzon

A century before, Utzon was anticipated by John Ruskin. Ruskin was not alone in extolling nature as a sublime model for design, painting, and sculpture – Thoreau was more concerned about its conservation against aggressive human impacts and encroaching industrialization. In Scandinavia, European Romanticism found expression in a National Romantic movement, which activated Utzon’s interest in the exploration of Mayan temples, Mesa Verde and the vernacular architecture of towns in the foothills of the Atlas Mountains in Morocco. They became his inspirational models, on which he came to base his idea of an organic sense permeating building.

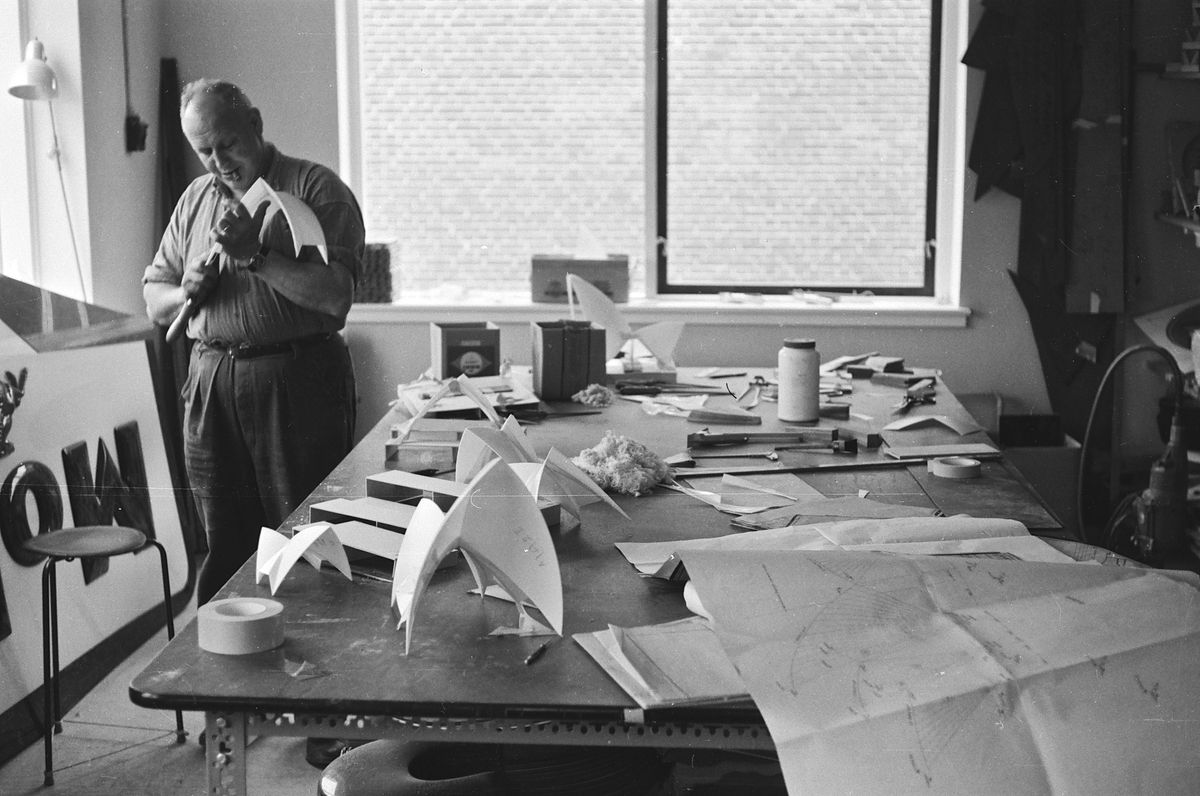

In the 1950s, the Super8 movie camera placed film-making in the hands of the amateur. Like many family men, Utzon was enthralled by the technology and quickly recognized its potential to record his travels and architecture in a new dimension – time. He could walk around, move in close and go inside buildings while filming his experience. The Super8 facilitated a new way of seeing architecture. Art is largely about new modes of seeing. The discovery of perspective sparked the Renaissance, a new visual culture, which, in turn, produced a new conception of space. Perspective set up the single viewpoint and ordered Renaissance pictorial space; Cubism changed this by seeing space serially in time from multiple viewpoints, thereby revolutionizing Modern twentieth century space. Space no longer expanded outwards from a single perspective viewpoint – buildings were experienced as a series of rapidly changing perspectives that merged holistically in a continuous sequence of overlapping visual frames. Cubism had earlier explored this, now the movie camera, captured a dynamic unfolding of space. Video technology has now replaced the Super8.

In 1941, the Swiss historian, Sigfried Giedion, deliberately titled his Norton Lecture series on Modern architecture at Harvard University Space, Time and Architecture to focus attention on the unifying centrality of the new space concept for the modern era. Utzon’s amateur film making was a practical application that directly addressed the new space as experiential and phenomenal. Like many architects, he filmed his architectural adventures. Later when he ventured into China in 1959, he took his movie camera with him to record what he saw.

In March 1959, Utzon arranged to meet a fellow Danish architect in Beijing, entering at the Hong Kong border. By then, he was busy in the early stages of the Opera House and arrived at the Chinese entry passport control carrying an expired visa and was refused entry, whereupon he announced to the officials he had been personally invited by no less than Chairman Mao Zedong himself. This left the officials to ponder their next action—to allow Utzon in or telephone Mao to confirm Utzon’s claim and invite the wrath of China’s supreme ruler! They chose the least explosive alternative, and stamped Utzon’s expired visa without further ado. Only Utzon could have pulled off such a brazen bluff. It worked and set the pattern for later encounters with Chinese officialdom when, on leaving China during a period of heavy paranoid repression, his extensive collection of photographs and films was withheld.

His friend had no so luck – on arriving in Beijing, he was summarily thrown in prison as a spy and was only released on Utzon’s cognizance.

It was a crucial time for Utzon. Economic conditions in Denmark were tough, even with Marshall Plan aid and there was little building happening. This left Utzon with time for travel, which, supported by scholarships, was an opportunity he avidly exploited. Thor Heyerdahl traversed the South Pacific to Polynesia on the Kon-Tiki expedition in 1947, Utzon, likewise, wished for adventure, and travel back then, was not the mass activity it is today.

“Living architecture” is a puzzling idea, too vague to tie down, other than its suggestion of an organic approach. Only when it is connected to sculpture does it begin to make any sense. It offered a way out of the dehumanizing bind Le Corbusier locked himself into with his 1920s premise that houses were no more than “machines for living.” “Living architecture” was not only more persuasive with its suggestion of a more human approach over the mechanical, it was eminently Danish in its promise of softening the impact of the industrialization of the building process.

A sketch of a platform in Yucatan, Mexico.

Image: Jørn Utzon

A sketch of the platform and roof forms of the Sydney Opera House.

Image: Jørn Utzon

What exactly did Utzon discover in the jungles of Yucatàn? His diary is informative. Whilst visiting the palace in the ancient Mayan city of Uxmal, he encountered an extraordinary sculpture which occasioned this detailed description:

“What mainly sets Uxmal part from other structures I have seen,” Utzon wrote, “was the rich, almost extravagant detailing; almost every stone was sculpted with animal motifs such as snakes, birds, toads, turtles, either once or as a repeated pattern to form borders or cornices, while richly ornamented human beings, half in relief, or in some places, for instance, in the corners, almost completely carved out, almost as free-standing sculptures, were taking up the space in the middle. One of the most profound ornament was a snake motif, where all the stones in the snake’s body were the same, however, because of the intricate interlocking system, it was possible to turn these joints in different directions, making the snake twist on the surface that was 5 metres tall and 30 to 40 metres long while still remaining interlocked with the rest of the stonework. This is the best example I have ever seen, where one can really say what is architecture and what is sculpture because everything is working together to create a sense of the whole.”

Only when “living architecture” is linked to sculpture, and sculpture to architecture as a whole, do we begin to fully comprehend what Utzon attempted in Sydney. Sculpture enlivens architecture, breathes life into it and makes it wriggle, twist and turn, much like the giant snake sculpture at Uxmal. It represents a profound shift in Modernism, an injection of primitive animism into the machine architecture of the twentieth century, which was meant to enliven, and, at the same time, humanize the new machine architecture. One feature of the Sydney Opera House where this idea is most obvious and successful occurs in the spherical tiled roofs. Utzon’s decision to incorporate two tile finishes, a glazed and a matt tile – the matt as a border, a mix of crushed tile fragments that break up the tile surface so it disperses the reflected sunlight – does something comparable to the interlocking stones of the Uxmal snake. Throughout the day, as clouds drift across the sky and the elevation and angle of the sun changes, the appearance the tiles also changes, imparting a living quality of light to the roof vaults.

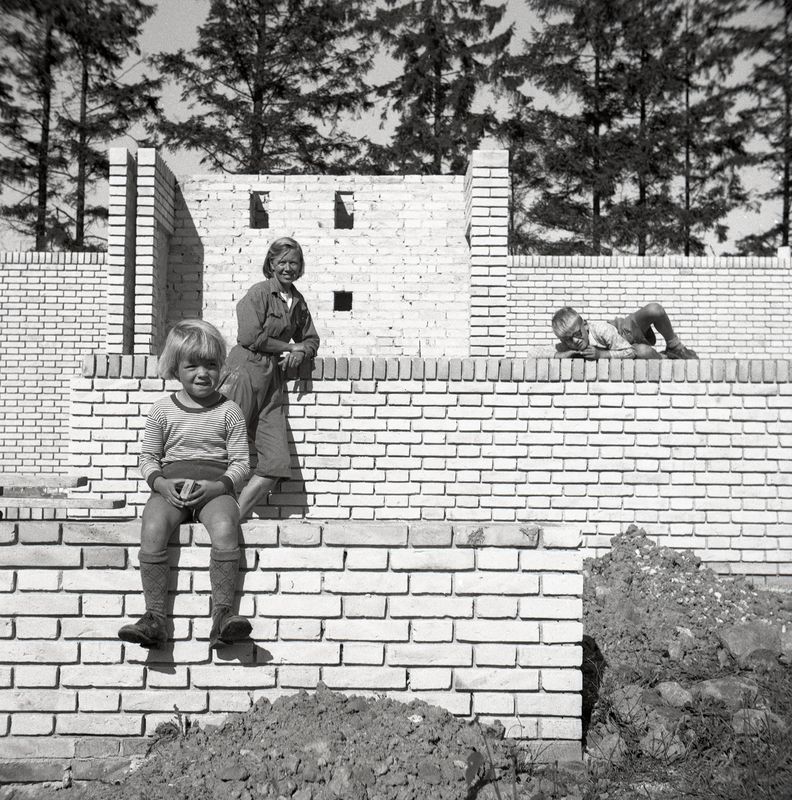

Utzon praised the Mayan practice of building their temples on top of massive platforms, a practice by no means confined to Central America, but also encountered in ancient Chinese, Greek, and even Polynesian buildings, all of whom raised their structures on platforms to separate their architecture from its surroundings. Utzon adopted platforms with an entirely different agenda, not to separate, rather, to unite building with landscape.

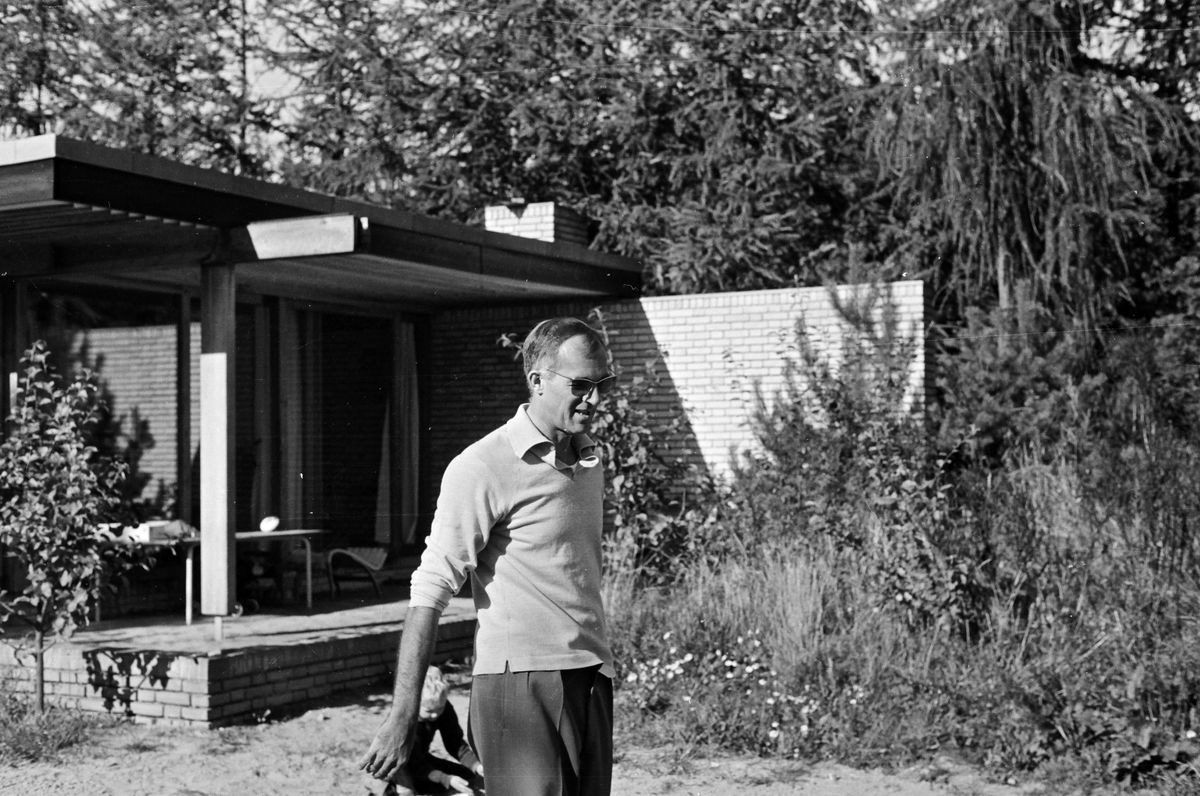

Morocco is the key to Utzon’s second key concept of architecture as landscape: in the hill villages he visited, buildings were made of mud brick. Their placement was not regulated as in the West, they related as groups, it being left to each individual builder as to how he chose to site his house in relation to neighbours, with an obvious sculptural benefit in terms of the form of the group.

Utzon was impressed by the result:

“All the houses were the same colour as the ground we stood on, yet they were full of subtle shades. And when they were building—they were almost always working on something somewhere—they sang. Always in rhythm with the way in which they stamped the clay in oblong moulds—almost three or four metres long and about seventy-five centimetres high. Always accompanied by singing. Every house was so beautifully placed quite unlike the conformity of houses in Denmark and Sweden. Here the buildings are placed in relation to each other and in relation to the undulations of the terrain. I was profoundly inspired by the way of building in natural surroundings.”

The connection between Morocco’s vernacular Atlas houses and Utzon’s later Kingo Houses estate, at Helsingør (Elsinor) 1957-59, and Fredensborg for the Danish Co-operative Building Company, 1962-63, is obvious. In both, the arrangement of each individual house unit is subtly aligned with respect to the terrain and in relation to its neighbour. This is demonstrated by the Helsingør example where the house units loosely encircle and enclose a small lake at the centre, and, at Fredensborg, the snake motif from Uxmal was reiterated in the sinuous snake like arrangement of the houses so they step up and down the sloping green hillside. The community meeting house as the central focus this time is at the top as the head of the snake.

Utzon discovered his direction early in his career in his thirties, and he would go on to apply and refine it, project by project. By treating the Mayan platform as an extended terrain Utzon unified architecture with its landscape surroundings, the bones of the landscape, while “living architecture” would in turn justify his treatment of architectural form as strong sculpture, architecture conceived in sculptural terms with a careful consideration of surface texture, involving subtle contrasts of material from rough to smooth, now becoming an important concern. This helped to humanize the driving idea behind Modern architecture which looked to architecture as a machine based culture. “Additive architecture” was Utzon’s answer, the simple combination of multiples, inspired by vernacular building around the globe.

Utzon’s photograph from Mexico, 1949.

Image: Jørn Utzon

Sigfried Giedion chose Utzon as his key representative for what he chose to call “the Third Generation” of Modern architects. It was an impressive honour and showed how highly Giedion the historian valued Utzon’s contribution to future architecture in the West as revolving around not only new technology, as a high technological civilization, but as demanding a rapprochement with the ancient past allowing the Modern Movement to assimilate its lessons on sculpture and symbolism in order to deal with the approaching challenge by new technology and its threat to reshape humanity in conformity with its image.

Utzon ventured well outside of safe surroundings, outside Denmark, in his quest for instructive examples. Unlike Arne Jacobsen, who pioneered Modern architecture in Denmark and remained profoundly Danish in sensibility, Utzon was inspired far more by what he encountered beyond Denmark and Scandinavia which produced a wildly eclectic brew. Vernacular buildings were a revelation, they offered new insights and models on how architecture might engage with nature. Importantly, it suggested ways for him to engage industrialized building through such ideas as his “kit of parts” and “additive architecture.” His open warm inclusive enthusiasm, ability to communicate with people, enabled Utzon to take in, absorb, and synthesize fresh insights from earlier civilizations that dealt with the challenges thrown up by the increasing repetitive standardization of building, and so avoid, overwhelming banality. Aalto set Utzon on this path, but it was his wider exploration, curiosity and openness that took him much farther.