The authorized view has held that architecture in Western Australia characterized by a dependence on received examples from the eastern states. In the move across the Nullarbor, these examples and ideas have been diluted by distance and then polluted by parochialism. Furthermore, the original source of this knowledge is even more remote, being centred in Europe and America. Certainly, J.M. Freeland, in his book Architecture in Australia, saw that:

“In general the story centres on Sydney and Melbourne. They are the magnets which have drawn both people and ideas from overseas and from which local influences have spread to affect the rest of the nation. While local factors have played a large part in determining Australia’s architecture, it is nevertheless true that the major developments have come as a result of changes on the other side of the world.

… New knowledge and new approaches arrive at the two large metropolises and thence, with a further time lag … to the other state capitals.” (Preface, p. 2)

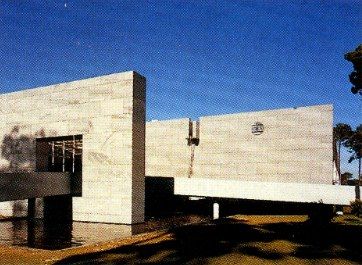

CRA Research and Development Facility by Steve Woodland of Forbes and Fitzhardinge.

This view is sustained by Donald Leslie Johnson in his later account, Australian Architecture 1901–1951: Sources of Modernism, where he asserts that the role of states like Western Australia “in relation to the rest of Australia appears to parallel in a micro-condition the role of Australia to the rest of the Western world.” (p. 212)

Revisionary histories are being written which allow that Western Australian architecture is not simply the last carriage in the train of received influences in Australia. The work which follows on these pages demonstrates that the isolation of Perth has meant that no priorities in the world of received ideas have been allowed to Sydney or Melbourne ahead of any other part of the world. And this has not been a recent phenomenon, but has always been the case. It is more a measure of the isolation of these historians than of Perth that architecture here has been constantly presented as a shallow reflection of work on the east coast. This misrepresentation has been identified in Western Towns and Building (Pitt-Morison and White editors), although there has been no attempt to correct it. Western Australia has always had an independence of endeavour, which has never been adequately acknowledged in the East.

From the earliest days of settlement in Perth, there has been a concern for the establishment of a fully suburban condition, with building and planning regulations supporting the separation and articulation of individual buildings. The city centre itself was built on residential lots, with their form of subdivision contributing in a distinctive way to the linear form of the city. As a result, Perth is like a never-ending garden suburb with a great sense of spaciousness and introduced greenery. Flying into Perth, one has a sense of a dusty oasis squeezed between the desert and the ocean. While Western Australian architects have always been skilled at designing and building the independent architectural object, they have not adequately tackled the problem of urban building. Perth has never been a city greatly concerned with the urban condition or the architectural forms which emerge in the tackling of these primarily European concerns.

International concerns for urbanism have recently been embraced in Perth, but there is little local tradition of urban practice to daw on. Attempts to create a new civic space in Forrest Place, the linkage of the new bus station through the heart of the city, and pedestrian connections between new major city projects, are all efforts in this regard.

Nor has Perth ever been a city concerned with public celebration through its architecture. The public buildings have an austerity about them, a minimalist frugality which allowed architectural modernism to be easily assimilated as an almost natural extension of a utilitarian tradition. Much of this austerity can be traced back to the impoverished conditions of the colony in the nineteenth century; and it continued into the twentieth century sustained by the myth of the pioneer. Without any commitment to a modernist orthodoxy, and with the freedom associated with geographic isolation, Perth’s early modern architects showed a great willingness to innovate, to invent from first principles. These experiments were in the realm of technological and constructional innovation, without great concern for issues of architectural form. The crafting of Perth architecture has always been an important component of local practice, where the process of putting together buildings in a sophisticated way has been a key measure of an architect’s skill, It has also been a means of mediating between cultural alienation and an alien landscape; to craft the natural is to reconcile the land with the landed, Nevertheless, frugality remains a priority even in this sphere, where range of materials, degree of servicing and tectonic flourishes are kept to a minimum. The pioneering spirit of “making-do” remains in force and challenges the need for the degree of architectural celebration and servicing that most late twentieth century cities assume as a standard for their buildings. Apart from the flourishes of the Gold Rush, architectural embellishment has been a recent phenomenon in Perth and is limited mainly to the private palaces of the suburbs.

Oasis by Mark Krynski, Steve Parkin and Lincoln Jones.

The work of young architects in Perth continues this ethos in the same physical land confronted by the ninetheeth century architects in Western Australia. These architects received their training on the other side of the world. The young architects are now born and educated in Western Australia. A typical pattern includes travel to Europe and the USA shortly after graduation and a return to Perth after several years. While some are still to leave WA, very few have worked or travelled in other parts of Australian – their orientations tend to be local and global rather than national. And this has probably always been the case. Their adopted strategies are clearly connected to their predecessors: a certain fundamentalism of approach, an austerity of expression and the logical resolution of the tectonics.

Central to the outlook of the most interesting of the young architects in Perth is a commitment to the culture of architecture, where architecture is a means of expression, an arena for conversation rather than rhetoric. They are dissatisfied with the limited role of the architect as the instrumentalist, providing architectural solutions to identified problems. These young architects have become involved in the staging of exhibitions, the undertaking of architectural competitions and the teaching of architecture within the schools. They have assisted in identifying and bringing international speakers directly to Perth rather than the usual repeat performance after the main bout in the eastern states. Recently young architects have worked with young artists in an exhibition titled Urban Thresholds to produce a series of site-specific and provocative installations within the central city and the cultural centre. Another group of newly graduated architects have recently curated and exhibited their own project work at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts.

The two schools of architecture in Perth are currently generating a real dynamic and showing the value of choice. The educational characteristics which always separated the schools at the University of Western Australia and Curtin University have now become more pronounced. But, interestingly, amongst the young architects and their colleagues within the schools, a key point of intersection seems to be the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London. The influence of the AA on Western Australian architecture has been significant but has yet to be studied in depth. Educators like Michael Beasley and Gordon Stephenson brought with them connections from the 1930s AA, while practitioners Peter Parkinson and Jeffery Howlett provide the immediate post World War II connections. Currently, AA-experienced educators represent by far and away the largest non-locally trained group within the schools.

In Perth there are only a few practices set up by young architects. There are not many young architects prepared to leave the protective world of the older, established practice and pursue a more self-directed architectural approach. However, a number of architects are taken on as partners in the established practices from a young age. They seem content to work within a more anonymous architectural tradition, as a contributor to the architectural team. This will inevitably lead to some good opportunities for younger architects and the possibility of more vital work emerging from the established practices.

Perth lacks a tradition of a clientele that is readily accepting of individual architectural expression, and there is little expectation in the profession that this should be the case. In performing an instrumental role, Perth architects have shown a preparedness to sustain late-modernist abstraction as a ready means of architectural anonymity – yet, by crafting the means, and by investigating new sources for abstraction, they are extending the architectural boundary.

Much of the work by younger architects still demonstrates the concern for the utilitarian, contained within the frugal forms generated by formal conservatism. The plan is the primary architectural reference, with space, elevation and section as a consequence rather than an arena for speculation. The architecture remains haunted by the conservative and practical. But what marks the young architects identified for this review is a willingness to be open to new possibilities. Intellectual rigour is re-evaluating WA’s conservatism as a springboard for experimentation.

Artistic exploration is showing practice and the practical to be powerful fields for expression. Their work deserves the accolade of criticism.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 2 May 1990

Words:

Geoffrey London,

Simon Anderson

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 1990