In the south-east of Tasmania, beyond Eaglehawk Neck and across the bay from Port Arthur, the Tasmanian Walking Company (TWC) continues the legacy of more than thirty years of guided walks in Australia’s southern state. TWC’s four-day Three Capes Walk traces the edges of the dolerite cliffs of the Tasman Peninsula, three hundred metres above sea level, with a series of new buildings designed by Andrew Burns providing a place of luxurious repose at the end of each day.

Located on two sites, one on either side of the peninsula, the buildings draw on TWC’s lineage of groundbreaking projects by Ken Latona and Joan Masterman, who established the Cradle Mountain Lodges in 1987 and Friendly Beaches Lodge in 1992, in addition to Latona’s third venture at Bay of Fires in 2000 (see Architecture Australia, July 2000). Inspired by the popularity of New Zealand’s Milford Track, Latona and Masterman created a new mode of tourism for Australia, offering relatively modest facilities as part of guided and fully catered walks. Central to these projects was a belief in the primacy of the place, rather than a focus on heroic or iconic architecture. Interviewed for the New York Times in 2001, Latona noted, “I do really believe that people go to these places to see the places. They don’t go there to see fancy buildings. The architecture can be quite humble.”

For the Three Capes Track Lodges, Andrew Burns has drawn on Latona’s legacy in myriad ways, providing a generous guest experience with sensitive, place-based architecture. Formally, the architecture references Latona’s Bay of Fires building, notably the profiled metal roof supported by exposed outriggers, which is translated into a fine assembly of steel plates and a custom-profiled gutter to create a sense of lightness and a formal consistency between TWC’s various projects. The siting strategy is also similar, with buildings nestled into the landscape, providing a contrast between the intimate setting of the bush and the dramatic (and sometimes wild) coastal edge. Burns describes the siting process as “taking the lead from the existing structure of the site,” placing buildings in clearings and adjusting to the landscape’s contours.

The Cape Pillar site has a more elaborate complex of pavilions wound within the landscape, with the buildings following the contours of the site.

Two locations are occupied: Crescent Lodge, to the west of the peninsula, is the destination for the first night, and Cape Pillar to the east hosts guests for the second and third evenings. On both sites, the form and placement of buildings orchestrates movement and experience, establishing particular visual connections far and near. Burns used an iterative process of revisiting the sites and adjusting the building orientation to align the buildings on axis with key views to Cape Raoul and Cape Hauy.

At Crescent Lodge, the journey along a narrow bush track arrives at the midpoint along the northern edge of a linear pavilion, where a sheltered porch allows guests to unload backpacks and strip off jackets and shoes. The building steps eastward, back up the hill, to a series of sleeping pods on different levels and communal bathrooms accessed via an open verandah. Projecting westward towards the expansive view of Cape Raoul, the communal spaces are entered through a pair of parallel corridors for staff and guests. As visitors step across the threshold, they move through an enclosed timber volume lined with coat racks to one side and a long built-in sideboard servery along the other. Past an open kitchen and a central island bench, the solid walls are replaced by operable glazed panels, and the dining and sitting spaces open laterally into the landscape. The pavilion becomes a platform, seamlessly connecting outside and inside. Further down the slope to the south, a smaller pavilion provides a second secluded sitting room.

Cape Pillar’s partially enclosed timber living space opens out to the landscape and frames a distant view to Cape Hauy.

Image: Brett Boardman

The second site at Cape Pillar has a more elaborate complex of buildings wound within the landscape, with a branched sequence of paths connecting the communal and private spaces. Guests arrive at a large deck, to a view that is framed through the deep and wide opening of the lounge pavilion. Turning back, away from the view, the path leads up stairs to a familiar sequence of spaces, with the kitchen and living pavilion to the north and sleeping pods and bathrooms in a separate pavilion to the south. The central living pavilion mirrors the pattern of Crescent Lodge, the enclosed timber embrace of its entry connecting to spaces that open out to the landscape, with the distant view to Cape Hauy visible beyond.

Straddling glamping and hotel accommodation, the site’s shared bathrooms and rudimentary sleeping accommodation contrast with the luxurious communal spaces. At Crescent Lodge, the sleeping pods are positioned high on the hill, opening out to the expansive view; whereas at Cape Pillar, they shelter within the bush, with the trees providing an intimate screen that veils the distant views. Both create a strong sense of being perched among the treetops.

The logistics of construction was central to the design process, particularly the necessity for airlifting materials to the sites. The building was designed to allow maximum flexibility in construction techniques and was ultimately delivered through a combination of prefabricated components – the sleeping pod modules, wall panels and long-span trusses – and onsite construction. The buildings operate off-grid, with solar panels mounted out of sight on the roof. Power is supplemented by bottled gas, and waste is removed in fly-in-fly-out pods that are collected periodically by helicopter.

Architect Andrew Burns has drawn on the lineage of walking lodges designed by Ken Latona. Profiled metal roofs supported by exposed outriggers reference Latona’s design for the Bay of Fires building.

Image: Brett Boardman

The new lodges complement the excellent Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service (PWS) facilities, designed by Jaws Architects, which opened in 2015. This PWS site serves as the fire refuge for TWC guests, and this meant that the asset protection zones could be relaxed in this project. Buildings were positioned to minimize impact on threatened flora, but were able to be positioned closer to other tree species. This assisted in managing bird strikes by reducing the risk of high-speed collisions, and large eaves, glass with low reflectivity and drop-down screens to reduce “fly throughs” where also employed.

Central to the experience are the guides, who bring their local knowledge and love of the landscape and the place to the fore. As Rory Spence noted in his 2000 review of the Bay of Fires Lodge, the structure of the spaces allows the staff to become “part of the social group, undermining the served/servant stereotype of the ‘hospitality’ industry.” In both projects, the building provides the perfect armature for nestling people into the landscape, completely in the lap of luxury yet also embedded in nature.

For the new owners of the Tasmanian Walking Company, Brett Godfrey and Rob Sherrard, it was critical that these projects carried on Latona’s legacy. The detail briefing, site investigation and the process of commissioning architects and builders were all designed to create the best conditions for a very refined project. The design and construction process and the complexities of the remote site required a commitment from both architect and builder that extended beyond the standard level of engagement. The unrelenting attention to detail has paid off well, with a fine set of buildings that creates a strong sense of place, setting up the next thirty years of adventures in this amazing location.

Credits

- Project

- Three Capes Track Lodges

- Architect

- Andrew Burns Architect

Chippendale, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Project Team

- Andrew Burns, Jordan Soriot, Casey Bryant, Alex Galego

- Consultants

-

Builder

AJR Construct

Geotechnical consultants Geo-Environmental Solutions

Planning consultant ERA Planning

Project manager – design and documentation Kate Gooch

Services engineer JHA Consulting Engineers

Structural engineer SDA Structures

Viewshed analysis consultant Another Perspective

- Site Details

-

Site type

Coastal

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2018

Category Hospitality

Type Hotels / accommodation

Source

Project

Published online: 2 Sep 2019

Words:

Helen Norrie

Images:

Brett Boardman

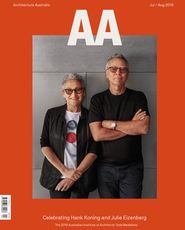

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2019